Pushing Boundaries – Chinese Diplomatic and Military Behavior Intensifies in the Run-up to the 19th Party Congress

Publication: China Brief Volume: 17 Issue: 11

By:

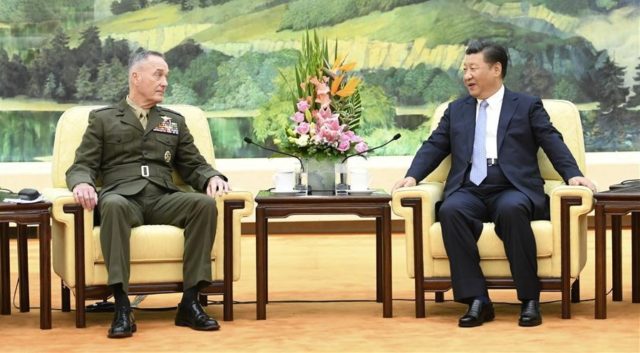

Amid rising tensions between the United States and North Korea, Gen. Fang Fenghui (房峰辉) greeted his American counterpart, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Joseph Dunford in Beijing on August 14. Recognizing the necessity of clear communication as the U.S. assesses possible military action against North Korea, the two held talks targeted at “mitigat[ing] the risk of miscalculation in the region” (Takungpao, August 15; Pengpai, August 15).

Although both parties are aligned in their desire for stability on the Korean Peninsula, China’s relations with the United States and its neighbors have worsened over the course of 2017. From its border with India, to the East China Sea, China appears to have decided to ratchet up, rather than moderate, areas of friction. In the case of the U.S., tension is rising over possible trade war, right as China is entering an important political season. More than ever, it is important to understand the factors that go into determining China’s willingness to use force, expend political capital, and confidence when challenging its neighbors.

A review of China’s recent diplomatic and military actions—and their impact on U.S.-China ties—can provide some useful context as both sides attempt to cooperate on North Korea and other issues.

China has achieved a number of important diplomatic successes in the first eight months of 2017. Perhaps the most important progress was seen in China’s long attempt to undermine international support for the Republic of China (Taiwan). Particularly after the effective setback the People’s Republic of China (PRC) experienced when Democratic Progressive Party candidate Tsai Ing-Wen was elected to the ROC’s presidency in 2016, the PRC has made significant headway in reducing the ROC’s diplomatic presence abroad.

In January, Nigeria closed a Republic of China trade mission in its capital, Abuja. This followed São Tomé and Príncipe‘s switch in recognition to the PRC in December 2016 (ROC-Taiwan.org, December 21, 2016). In early June, Panama cut ties with the ROC and recognized the PRC. Taiwan is consistently rated at the top of China’s diplomatic and military objectives, and as of August 2017, only 20 nations worldwide recognize the Republic of China. These successes can be expected to embolden China’s use of economic diplomacy to effectively sway other countries to support its causes.

In Southeast Asia, targeted Chinese diplomacy and distrust of U.S. commitment to involvement in the South China Sea appears to be having an effect. Little more than a year after an international tribunal ruled in favor of the Philippines’ territorial claims in the South China Sea, China enjoys unprecedented influence in Manila. Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, who regularly criticizes the U.S., has moderated his stance somewhat as he enlists U.S. military support to deal with a terrorist crisis in the south of his country. However, his eagerness to improve ties with China, and plans for large Chinese investments, will remain important parts of his political platform.

To the west, Vietnam has entered a particularly tense stage of relations with China. In July, Vietnam withdrew oil drilling ships in the East China Sea after China threatened military action. This followed earlier tensions in June that resulted in Central Military Commission Vice-Chairman Fan Changlong (范长龙) cutting short his visit (Xinhua, June 18). In both cases the level of animosity, as the two nations maintain close ties at the Party-to-Party level, and have a number of off-ramps to decrease tensions. But with the withdrawal of the drilling ships it is clear who has the upper hand. China’s position in the South China Sea—via carrot and stick—is more secure than ever and the lack of major cohesive pushback from Southeast Asian nations is having is generating national confidence in China’s rise.

This confidence in dealing with its neighbors is reflected with a generally upbeat feeling among Chinese nationalists at home. On July 1, the PRC celebrated the 20th anniversary of the handover of Hong Kong. The celebrations were meant to emphasize that whatever “One Country, Two Systems” may imply, Hong Kong was firmly part of the Mainland. China’s sole active aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, visited Hong Kong harbor and hosted current and former Hong Kong Chief Executives—Beijing’s appointed stewards—Carrie Lam, Leung Chun-ying and Tung Chee-hwa (SCMP, July 7). Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lu Kang even took a victory lap, stating that the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which had guaranteed a “high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defense affairs” through 2047 “no longer has any practical significance nor any binding force on the central government’s administration of Hong Kong SAR” (Xinhua, June 30). [1] This is understood to undermine the “One Country, Two Systems” plan outlined from Hong Kong, and for PRC-proposed plans for peaceful integration of Taiwan.

In a year that marks the 90th founding of the People’s Liberation Army, the Chinese military has made a series of symbolic and concrete advances. Nationalistic, feel-good events included the April launch of China’s first domestically produced aircraft carrier. For the PLA, an August celebratory parade—traditionally held in Beijing—was instead broadcast from the Zhurihe training ground and included more realistic operations (see the full analysis of the parade in this issue).

China’s diplomatic and symbolic achievements are mirrored, perhaps, in its military’s new confidence. Indeed, China’s military had a number of real confrontations with its neighbors and the U.S. military.

The Chinese military is also stepping up its long-range patrols near Japan and Taiwan. While the Chinese Air Force frequently visits the ‘center-line’ between the PRC and ROC (an ROC white paper recorded an average of 1,385 flights per year between 2004 and 2007), they now regularly circle the island and collect electronic information. ROC Ministry of Defense Spokesperson Major General Chen Chung-chi emphasized that these are normal activities (UDN [Taiwan], August 10). [2] However, in aggregate the PLA Air Force appears to be increasing its activity. The Japanese Air Self Defense Force continued to see a yearly increase in the number of scrambles to intercept Chinese aircraft. [3] In May, a Chinese fighter jet flew upside-down over a U.S. plane collecting data about North Korean nuclear tests. In a series of incidents during June and July, Chinese jets performed aggressive interceptions of U.S. electronic surveillance aircraft of the East China Sea. While Chinese interceptions of U.S. flights are routine, the decision to allow such unsafe behavior is instructive. And whereas Chinese jets conducting long-distance flights near Japan tend to be lightly armed, if at all, footage of Chinese intercepts reveal they carry a full weapons load when intercepting U.S. aircraft.

Chinese navy ships are traveling much further afield than they traditionally did. A small group from the South Sea Fleet recently participated with their Russian counterparts in the Baltic Sea. Chinese signals intelligence ships were spotted off the coast of Alaska for the first time, likely to observe a U.S. missile test (Sina, July 14).

In mid-June of this year Indian soldiers confronted Chinese troops building a road along the border between China and Bhutan. Although both sides regularly interact at the small unit level at a number of places along the border, in this case the situation escalated. The area is viewed by India and China as a strategic bottleneck, necessary for power, economic and cultural projection in the region (China Brief, April 20). In mid-August, similar confrontations took place along the western portion of China and India’s border near Pangong lake (Times of India, August 16). Together, these have pushed Sino-Indian relations to the tensest point since the 1980s.

Political and military decisions are not made in a vacuum. Some military training exercises are routine; sometimes errant behavior escalates unnecessarily. Overall, policy and the decision to exert diplomatic or political pressures are the result of deliberate decisions.

Though, not a popular democracy, China’s political system still rewards political deliverables—economic growth or other noteworthy achievements play a role in getting ahead for government cadres. The same goes for diplomatic and military achievements. Ahead of the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party planned for October, there may be increased willingness to more directly challenge the U.S. and its allies.

A second factor to consider is prestige as a motivation for diplomatic and military action. China’s successes in both fields have had real effects in increasing Chinese citizens sense of national confidence and pride. Although continuing internal challenges (rising local government and SOE debt, environmental issues and social inequality) and the militaries’ shortcomings (lack of realism in training, incomplete reforms) could act as a check on adventurism, more confident military and foreign policy behavior should be expected.

Throughout, the Chinese leadership appears to wish to maintain escalation control: adopting heavy-handed tactics while forcing other countries to acknowledge China’s ability to go further if needed.

Peter Wood is the Editor of China Brief. You can follow him on Twitter @PeterWood_PDW

Notes

- Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau, Joint Declaration, June 30, 1985 https://www.cmab.gov.hk/en/issues/jd2.htm

- Republic of China Ministry of Defense, National Defense Report 2008 p. 85

- In fiscal year 2016 the JASDF scrambled fighter jets 871 times compared to 571 in 2015. Ministry of Defense Joint Staff, Statistics On Scrambles Through Fiscal Year 2016,

- https://www.mod.go.jp/js/Press/press2017/press_pdf/p20170413_02.pdf