Chinese Incursions Into Vietnamese Waters, Security Implications for the Region, and the Potential Role of India

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 10

By:

Introduction: China Renews Its Maritime Sovereignty Claims at the Expense of Vietnam

The outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic that began in the Chinese city of Wuhan has not deterred the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from pursuing its long-term strategic vision of asserting its sovereignty in the South China Sea (SCS) at the expense of smaller regional countries. The SCS has long been a potential flashpoint, as half a dozen countries make contending sovereignty claims—and China claims almost the entire region. In one of the most recent incidents on April 2, a Vietnamese fishing vessel near Vietnam’s Hoang Sa (Paracel) Archipelago was sunk by the Chinese Coast Guard.

What exactly happened? The Vietnamese vessel (number QNg 90617 TS), with eight fishermen onboard, was attacked while fishing near the Paracel Archipelago’s Phu Lam Island. Following the incident, Vietnam lodged an official complaint with the PRC (VNA, April 20). To further complicate the matter, China recently sent a survey vessel into Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), in a move likely to fuel tensions further. Vietnam responded by sending three ships from the Fisheries Resource Surveillance Agency to closely trail the Chinese vessel. The situation and composition of China’s naval incursion is reminiscent of past confrontations between Vietnam and China in the SCS (Global Security, April 14).

The Chinese vessel at the center of this incident, the Haiyang Dizhi 8 (海洋地质八号, Haiyang Dizhi Ba Hao) was also involved in a collision at the heart of the tense July 2019 standoff over the Vanguard Bank, a reef in the SCS controlled by Vietnam. The PRC sent the Haiyang Dizhi 8, along with coast guard escorts, to put pressure on a Russian-owned oil exploration project within Vietnam’s EEZ. This prompted Vietnam to send its own coast guard and maritime militia vessels to the area. The standoff did not end until November 2019, and represented the worst flare-up in Vietnam-China relations since the 2014 standoff over the Hai Yang Shi You 981 oil rig. [1]

Of note, Haiyang Dizhi 8 was the same vessel involved in conducting survey operations in the EEZs of Malaysia and Brunei in mid-April of this year, further reinforcing Beijing’s expansive reach across the contested South China Sea (China Brief, May 1). The PRC and Brunei have agreed in the past to joint exploration over energy resources in Brunei’s part of the region, but it was not immediately clear if the current activities were part of that deal. Technically, a research vessel would need to request permission before operating within another country’s EEZ. It appears that Beijing is exploiting the COVID-19 pandemic to expand its “unlawful claims” in the South China Sea (Japan Times, April 27).

The Regional Implications of Sino-Vietnamese Disputes in the SCS

Vietnam has historically resisted foreign domination, and has not been shy in the past about confronting China. The most recent action by the PRC comes in the wake of a March 30 submission by Vietnam to the United Nations, which reiterated Vietnam’s own territorial claims to the Paracel and Spratly Islands (Hanoi Times, April 7). The PRC termed the Vietnamese assertion “illegal and invalid.” Today, Vietnam has reason to feel confident in its ability to resist China, due in part to closer ties with regional states—including the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which Vietnam holds the chairmanship this year.

The PRC’s actions in the SCS have been condemned by many stakeholders. The U.S. Department of Defense issued a press release expressing concern about the April 9 incident, stating that “The PRC’s behavior stands in contrast to the United States’ vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific region, in which all nations, large and small, are secure in their sovereignty, free from coercion, and able to pursue economic growth consistent with accepted international rules and norms” (U.S. Department of Defense, April 9). This same policy was also articulated by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in his address at the Shangri La dialogue in June 2018 (Indian Ministry of External Affairs, June 1). These principles enjoy widespread support in the region, even though many Southeast Asian states are reluctant to confront Beijing directly.

Beijing has not backed down from the negative international reactions resulting from its actions. On April 21, PRC Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang stated that “China will take all necessary measures to safeguard its sovereignty, rights and interests in the South China Sea” (China Daily, April 21). In response to the confrontation between China and Malaysia, the United States and Australia sent maritime forces to the area, which the PRC later claimed to have “chased off” (Global Times, April 28).

India’s Interests in Relation to the SCS Disputes

During this latest round of tensions in the South China Sea, another rising Asian giant with substantial stakes in the conflict has been conspicuously quiet. India has strong economic and growing defense relationships in the region. What are Indian stakes in the region, and how is it confronting the China challenge in the South China Sea?

India and Vietnam have long-standing historic ties, which continue to grow as a result of the security challenges in the SCS and New Delhi’s strategic interest in the region. India has a strategic partnership with Vietnam (which was upgraded to a “comprehensive strategic partnership” during Modi’s visit to Vietnam in September 2016), and the country is an important anchor to India’s “Act East Policy.” India’s maritime security posture and national interests demonstrate a strong commitment to align with the ASEAN countries. The Indian Navy’s 2007 doctrine defined the SCS as “an area of strategic interest.” Despite this, however, India is often caught balancing its legitimate interests with medium- to long-term challenges (Takshashila Institution, March 2016; Financial Express, September 2, 2019). 97 percent of India’s trade is conducted by maritime shipping, with 55 percent of the total transiting the Malacca Straits and the SCS (MEA.gov.in, February 9, 2017). Trade with the ASEAN states stands at approximately $80 billion, and as of 2018 comprised over 10 percent of India’s total exports (MEA.gov.in, August 2018).

The PRC is unlikely to replace India as the dominant player in the Indian Ocean in the short term, but China represents a significant challenge to India’s long-term interests in the region. Over the past two decades, China has added more than eight times the number of ships and submarines to its navy in comparison to India (Financial Express, May 1). PLAN submarines now regularly traverse the Malacca Straits to patrol the Indian Ocean. New Delhi, for its part, has expressed a commitment to defending its interests in the SCS, and has enacted several policies to begin countering active Chinese influence.

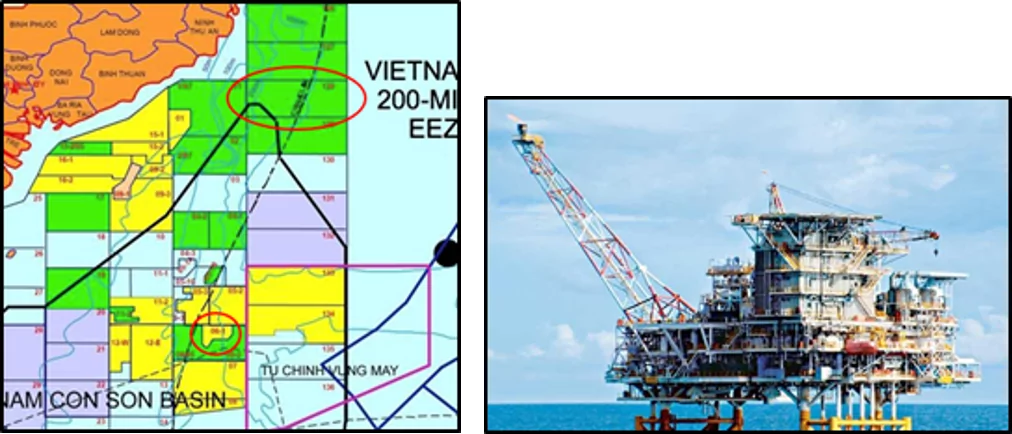

In addition, India has stated in no uncertain terms that it would deploy the Indian Navy to the SCS to defend its energy interests. India’s strategic interest clearly lies in maintaining peace and maritime order in the region. Oil Videsh Limited (OVL), the overseas operations branch of India’s public sector Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), has been engaged in oil exploration activities in Vietnam’s EEZ for over 30 years. India is concerned about the energy contracts signed with its Vietnamese partner. At present, OVL is operating two oil blocks in the South China Sea. The first of these, Block 128, is 7,000 square kilometers and was acquired in 2006; in July 2017, Vietnam extended OVL’s contract for an additional two years. The second block, Block 06/1, is less than 1,000 square kilometers and lies near the locations of recent Chinese provocations.

Image right: A file photo (undated) of an oil platform in Vietnam’s offshore Lan Tay field; the platform is co-operated in part by India’s ONGC Videsh and Vietnam’s state-owned Petro-Vietnam. India’s cooperative oil exploration deals with Vietnam are one of the factors that give it a greater direct interest in Sino-Vietnamese territorial disputes in the South China Sea. (Image source: Hindustan Times)

Indian concerns lie in fears that the PRC is trying to convert the SCS into its own “territorial sea,” thereby blocking or increasing the political and economic costs of any country attempting to trade or transit through the region. Such a possibility would negatively affect India’s economic rise. As China’s militarization and island reclamation activities in the SCS continue, smaller claimant nations have begun looking to India to enhance its role as a security provider in the region, as on their own each one is incapable of coping with the China challenge. In 2017’s Delhi Dialogue IX, an annual event to promote economic and politico-military discussion between India and ASEAN, Vietnam Deputy Prime Minister Pham Binh Minh said that “ASEAN supports India to play a greater role in the political and security domain…We hope India will continue to partner our efforts for strategic security and freedom of navigation in [the] South China Sea” (The Hindu, July 4, 2017).

Thus far, the Indian Navy has maintained its focus on the Indian Ocean region, ranging from the Gulf of Aden to the Malacca Straits—but it has an eye on the SCS, as well. In December 2012, then-Indian Naval Chief DK Joshi, in a significant assertion of maritime thinking, remarked on the eve of Navy Day that “Not that we expect to be in [the SCS] very frequently, but when the requirement is there for situations where [India’s] interests are involved, for example ONGC Videsh, we will be required to go there and we are prepared for that” (India Today, December 3, 2012).

India has since expanded its position and role in the SCS. From May 19-22 of this year, India conducted bilateral naval drills in the region (Economic Times, May 19). In May 2019, India conducted naval maneuvers in the sea alongside naval forces from the United States, Japan, and Philippines (TheWeek.in, May 9, 2019). Indian sources have indicated that New Delhi is considering inviting Australia to the upcoming Malabar Exercise (a yearly U.S.-Japan-India naval exercise), which is set to take place in July and August. Should this occur, it would represent a new step in the militarization of the “Quad” relationship of Indo-Pacific democratic powers. India has historically resisted such a security focus for the Quad, due to worries of provoking a negative Chinese reaction. Should Australia join the exercise, it would be the latest signal of New Delhi’s increasing willingness to confront Beijing (Times of India, January 29).

Conclusion

China’s consolidation of its position in the SCS would inevitably threaten Indian pre-eminence closer to home, in the Indian Ocean. Chinese submarine activity in the Indian Ocean region has become a large security concern for New Delhi. The move by a Chinese state-owned enterprise to attain a 99-year lease to the port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka raised alarms for Indian policymakers, as did reports of a potential Chinese military base being constructed in Cambodia (China Brief, August 14, 2019; China Brief, April 13). Such bases could potentially threaten Indian assets in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. On December 18, 2019, a Chinese research vessel intruding into Indian waters near Port Blair, in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, was expelled by the Indian Navy (Times of India, December 18, 2019).

Land-based border confrontations along the unsettled Sino-Indian border also continue to strain relations between the two countries. On May 5, 250 Indian and Chinese troops confronted each other with iron rods, sticks, and stones near the Pangong Tso Lake of Ladakh in the Kashmir Region. Separately, on May 9, 150 Indian and Chinese army personnel faced off near the Naku La Pass of Sikkim in northeast India, resulting in over a dozen injuries (Zee News, May 21). While these border confrontations are not necessarily related to the latest situation in the SCS, it reinforces Indian motivations to increase ties with Western powers and ASEAN members who are also the subject of Chinese coercion.

Professor Rajaram Panda is a Lok Sabha Research Fellow, Parliament of India and Member, Governing Council of Indian Council of World Affairs, and Centre for Security and Strategic Studies, both in New Delhi. He was also Senior Fellow at IDSA and ICCR Chair Professor at Reitaku University, Japan. He may be reached at: rajaram.panda@gmail.com

Notes

[1] In the Hai Yang Shi You 981 oil rig incident of 2014, China built an oil rig in disputed waters, and dispatched coastguard and maritime militia vessels to act as protection. See: “Vietnam Accuses Chinese Ships of Ramping Up South China Sea Tensions,” South China Morning Post, October 4, 2019.https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3031603/vietnam-accuses-chinese-ships-ramping-south-china-sea-tensions.