Downsizing the PLA, Part 1: Military Discharge and Resettlement Policy, Past and Present

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 16

By:

This is Part 1 of a two-part series on the PLA’s planned personnel reduction and its implications in two parts. Part 1 summarizes Chinese military discharge mechanisms and discusses key trends and changes in discharge and resettlement policy since the last troop reduction in 2004. Part 2 identifies and assesses the major challenges posed by the downsizing effort amidst slowing economic growth, PLA modernization efforts, and state-sector economic reform.

Former Chinese military personnel represent a large and important constituency within Chinese society. Large numbers of young, mostly rural men and women join the PLA through China’s conscription system and either leave the PLA or continue their careers after a two-year stint. A smaller number stay on and advance through the ranks, or increasingly, join from universities to become officers. Retired PLA personnel have also become a vocal political force, evidenced most recently during a protest in which more than 1,000 veterans gathered in front of the Ministry of Defense to seek redress for unpaid discharge allowances and benefits (New Tang Dynasty News, October 11). In September 2015, Xi Jinping announced that 300,000 military personnel would be downsized, reducing the total size of the PLA from 2.3 million personnel to 2 million (People’s Daily, September 11, 2015), potentially further complicating the issue of veteran dissatisfaction. A year into the downsizing, few concrete details have emerged about the reduction and its implications for the Chinese economy and society that must absorb the downsized troops, one of the Chinese Communist Party’s most important constituencies. A close look at this demobilization process and the PLA’s plans for larger troop reductions provides important insights into the reorganization program and long-term modernization goals.

Leaving the PLA: Discharge and Resettlement Policies

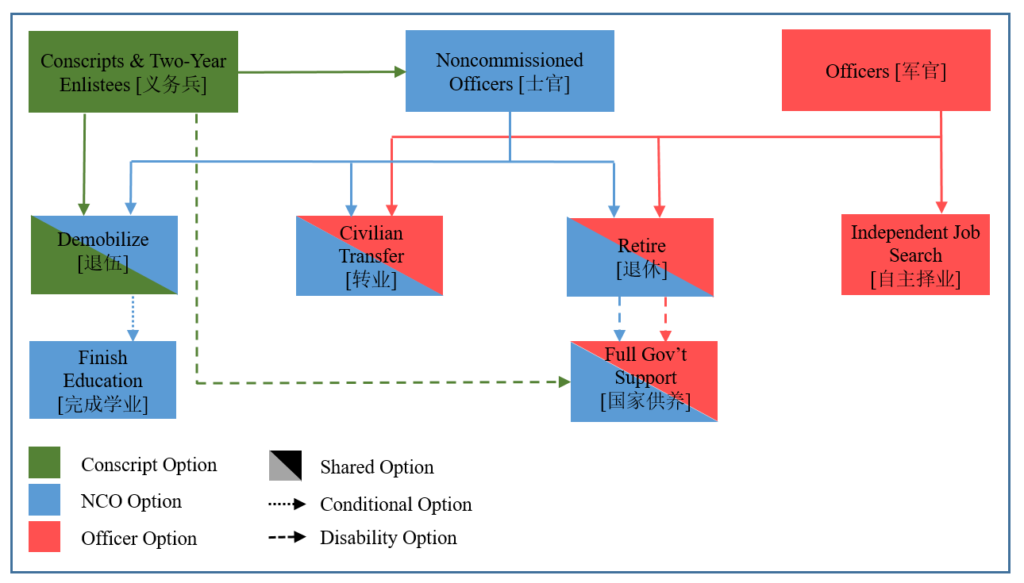

Soldiers leaving the PLA have a number of separation options available to them according to their grade and time in service. [1] The following descriptions of separation options and major benefits draw heavily on previous scholarly research and Chinese language sources from official state media, and are summarized below in Figures 1 and 2. [2]

Figure 1: Separation Options for PLA Servicemen

Figure 2: Separation Options and Major Associated Benefits for PLA Servicemen

| Separation Mechanism | Eligibility | Major Associated Benefits |

| Demobilize [退伍] | Conscripts; NCOs with less than 12 years of service |

|

| Finish Education [完成学业] | NCOs demobilized more than a year ago that have tested into a full-time higher education program, and are independently job-searching |

|

| Civilian Transfer [转业] | NCOs with more than 12 years of service; division-leader grade officers with less than 30 years of service; battalion-leader grade officers or lower with less than 20 years of service |

|

| Independent Job Search [自主择业] | Battalion and regiment-leader grade officers with more than 20 but less than 30 years of service |

|

| Retire [退休] | NCOs and officers at the age of 55 or with 30 or more years of service |

|

| Full Government Support [国家供养] | Conscripts, NCOs, and officers disabled in public service |

|

Conscripts and Two-Year Enlistees [yi wu bing; 义务兵]

As late as 2007, conscripts and two-year enlistees appeared to have only one main option for separation from the PLA. They could choose to simply be released from service [退伍] after their two-year service commitment with no government obligation to provide job placement, or they could decide to extend their term of service and become non-commissioned officers, after which they would enjoy the separation benefits and options described in the next section. Those that chose to leave have traditionally returned home and continued their old way of life. [3]

Conscripts and two-year enlistees that left after fulfilling their service obligation were entitled to certain benefits, including a small resettlement allowance and assistance in job-hunting. However, these entitlements had often been ignored or doled out unevenly across China, sparking complaints and aggravating civil-military tensions. [4] Dissatisfaction with inconsistent disbursement of benefits led the central government to codify the benefits available for discharged conscripts. The most obvious changes are manifested in 2011 revisions to the Military Service Law [中华人民共和国兵役法] and Enlisted Personnel Resettlement Regulations [退役士兵安置条例], which declared conscripts eligible for a one-time independent job-searching subsidy [自主就业一次性退役金], in which they would look for a job themselves and collect a one-time job-searching subsidy from the military (People’s Frontline News Weixin, August 8, 2015). As of September 2015, this one-time payment was 4,500 RMB ($674) for every year of service (PLA Daily Reporter’s Weixin, September 7, 2015).

Today, demobilized personnel receive a one-time demobilization subsidy [退伍补助费] of 2,000 RMB ($300), a one-time healthcare subsidy [退伍医疗补助费], a subsidy consisting of next month’s allowance [离队下月津贴], prorated living expenses for the month they leave [离队当月剩余天伙食费], and living expenses for the month after demobilization [离队下月伙食费] totaling up to 750 RMB ($112), in addition to the job-searching subsidy detailed above and additional healthcare and retirement subsidies (PLA Daily Reporter’s Weixin, September 7, 2015).

Non-commissioned officers (NCO) [shi guan; 士官]

Non-commissioned officers enjoy more separation options and benefits than conscripts do. As of 2007, enlisted personnel that had served up to an additional 6 years beyond their initial two-year conscription period were considered junior NCOs [初级士官] and were eligible only for demobilization [退伍]. Non-commissioned officers who had served 8–16 years beyond their initial two-year conscription period were referred to as mid-level NCOs [中级士官], and were eligible for transfer to civilian state positions [转业] after 10 years of total service. Senior-level NCOs [高级士官], or NCOs that had served at least 14 years beyond their conscription period, were eligible to retire [退休] after 30 years of total service. [5]

Major changes to discharge and resettlement policy enacted in 2011 expanded resettlement options and simplified discharge benefits. Revisions to the Military Service Law outlined five major discharge and resettlement options: independent job-searching [自主就业], government job placement [安排工作] (also known as civilian transfer, or zhuanye 转业), full retirement [退休], government support [供养], and completion of education [继续完成学业] (National People’s Congress, October 29, 2011). The 2011 revision to the Enlisted Personnel Resettlement Regulations simplified eligibility rules for military discharge benefits: NCOs who had served less than 12 total years would receive essentially the same benefits as conscripts, including the same one-time independent job-searching subsidy of 4,500 RMB ($674) per year of service from the military along with possible further financial subsidies from local provincial and municipal governments (State Council, November 1, 2011). NCOs who had served more than 12 years were eligible for government job placement (also known as anzhi, 安置), while those who had served at least 30 years, were disabled in war or public service, were 55 years or older, or had to retire for health reasons were eligible for full retirement or government support (State Council, November 1, 2011).

Officers [jun guan; 军官]

Officers and cadre [干部] have the most options available for separation from the PLA and enjoy greater benefits than enlisted personnel. [6] Officers are required to apply for separation from the PLA. Of those whose applications are accepted, officers who have served for 30 years are eligible for full retirement [退休]. Division-leader grade officers with less than 30 years of service and officers at the battalion-leader grade or lower with less than 20 years of service are to be transferred to civilian state employment [转业]. Battalion and regiment-leader grade officers who have served between 20 and 30 years are allowed either to accept a transfer to a civilian government job or accept a partial pension while they independently seek employment in the private sector [自主择业] (News of the Chinese Communist Party, January 19, 2001). [7]

Officers transferred to civilian positions are entitled to the same levels of pay and benefits they would have earned at their duty grade level in the PLA, and their years in military service count toward retirement at their civilian positions (State Council, July 31, 2015). Civilian transfers also collect subsidies for living expenses [生活补助费] and home settlement [安家补助费] (Ministry of National Defense, March 11, 2015). [8] Officers that choose to independently seek employment accept an 80 percent pension that persists unless they accept a job in the government sector (State Council, August 24, 2001). They are also eligible for a job search subsidy [自主择业补助费] on top of the living expenses and home settlement subsidies offered to civilian transfers (Ministry of National Defense, March 11, 2015). [9] Officers that retire collect full pensions and are eligible for a number of allowances, including one-time payments for living expenses and home settlement, along with housing, healthcare, and other benefits (Ministry of National Defense, March 11, 2015). [10] The subsidies vary in size according to different conditions: the living expenses subsidy is equal to four months’ pay, and the home settlement subsidy consists of eight months’ pay for troops returning to rural areas and six months’ pay for those returning to cities (Ministry of National Defense, March 11, 2015).

Regulations stipulate that most officers transferring to civilian government positions must return to the location of their original household registration [hukou; 户口], although at least one expert notes that some officers are allowed to stay in base housing and household registration reform may have loosened restrictions on where downsized personnel go. [11] Additional consideration is made for the locations of spouses or parents, although the policy does not elaborate on who makes the decision (News of the Communist Party, January 19, 2001). Those leaving the PLA under the auspices of independent job-searching [自主择业], as well as aviation and naval officers who have served 10 or more years, are also allowed a degree of flexibility in resettlement (News of the Communist Party, January 19, 2001). Although most officers will be placed according to their original hukou, decommissioned officers can also be placed in regions as needed by the nation (News of the Communist Party, January 19, 2001). A personnel management researcher at the PLA Logistics Academy noted that government departments in central and western China were “eagerly hunting for talented people,” indicating that some officers may simply be transferred to locations as needed rather than transferred home (China Military Online, September 9, 2015).

Full Government Support [guojia gongyang; 国家供养]

A special discharge option for all military personnel who are disabled in public service is full government support [国家供养], and includes considerable disability compensation payments based on the level and type of disability. Disabilities are classified on a scale of severity from 1 to 10 (Level 1 is the most severe) and sorted by combat, work, or illness disabilities. Personnel with disability ratings from Level 1 to Level 4 are eligible for full government support, and receive substantial compensation payments in addition to healthcare and housing allowances (Ministry of National Defense, March 10, 2015). For instance, enlisted personnel with Level 1 disabilities can receive a yearly compensation payment between 49,000 RMB ($7,335) for illness and 52,000 RMB ($7,784) for combat disability (Ministry of National Defense, March 10, 2015).

Key Trends in Discharge and Resettlement Policy

Changes in the PLA’s military discharge and resettlement processes since the last major troop reduction in 2003 can be characterized in three main ways:

First, conscripts and two-year enlistees have increasingly enjoyed greater benefits for their service, and as the PLA continues to seek more college-educated personnel, it will continue to feel compelled to better enforce existing military discharge policy and improve the conscript demobilization package by providing more generous benefits. The 2011 revisions to military discharge policy afforded much greater financial assistance to these personnel by opening up independent job selection to a group that was simply demobilized and returned home in the past. Some demobilized conscripts ostensibly leave the force with marketable job skills and useful certifications such as a driver’s license, although their employment prospects are in doubt in an economy that increasingly values higher-skilled workers. [12] The PLA faces no shortage of available conscripts as it transitions from an all-conscription force to a hybrid force with an increasing proportion of volunteer enlistees, but in recent years it has been forced to relax physical standards to attract better-educated personnel (China Daily, June 17, 2014). [13] As it continues to compete with the private sector for college-educated personnel, the PLA will have little choice but to continue increasing expenditures on demobilized conscripts as one way to attract desired talent.

Second, the PLA has placed increasing emphasis on higher education as an exit pathway, especially for its enlisted personnel. This is evident in the various incremental revisions to NCO discharge and resettlement policy. Starting in 2011, NCOs who have been demobilized for longer than a year, have tested into a full-time higher education program, and are participating in independent job-searching are also entitled to a yearly tuition subsidy of up to 6,000 RMB ($900) from provincial level governments—a figure that was adjusted upwards in 2014 to 8,000 RMB ($1200) a year for undergraduate programs and 12,000 RMB ($1,800) a year for graduate programs (Central People’s Government, October 31, 2011; Ministry of Finance, July 18, 2014). Demobilized enlisted personnel that choose independent job selection are also entitled to attend local government vocational education for up to two years at no cost (China Military Online, November 6, 2014).

Third, the civilian transfer process for officers has become increasingly competitive. Though the burden of resettling transferred officers is the legal responsibility of local governments and rejecting officers is not allowed, there appears to be a priority order for the best positions (News of the Chinese Communist Party, January 19, 2001; PLA Daily, July 5; Beijing Daily, July 15). In the interest of transparency, a 2012 document issued by the CPC Central Committee Organization Department [中组部], Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security [人社部], and the former PLA General Political Department [总政治部] stipulated that division and regimental-level officers eligible for civilian transfer would undergo an evaluation process [考核] that assigned civilian positions based on moral virtue, grade, military rank, length of service, specialty skills, hardship duty, and military commendations. Eligible officers at the battalion-level or lower would undergo the above evaluation process and an additional testing process [考试] administered by the receiving province, consisting of a written test and an in-person interview (Inner Mongolia Ministry of Human Resources, January 21, 2012). The competitive nature of civilian transfers has generated anxiety over transfer prospects, exemplified in a letter from a young company commander to the PLA Daily, in which the letter writer worries that he should apply for civilian transfer earlier rather than later in order to secure a better position, even though he does not yet qualify for transfer by virtue of grade or time in service (PLA Daily, July 5).

Conclusion

It is clear that the PLA and the relevant civilian agencies have adopted a series of discharge mechanisms and adapted them according to various needs and pressures. The PLA’s desire for college-educated enlisted personnel precipitated an increase in benefits for demobilized conscripts, while the looming expense and difficulty of finding jobs for NCOs led officials to highlight education as an increasingly important pathway for demobilized enlisted troops. The opacity of the officer civilian transfer process prompted officials to clarify the process in an attempt to defuse criticism from the affected group. In each case, the PLA and the relevant civilian agencies have taken deliberate steps to address a need or a potential problem. Will these steps be enough for Chinese civil society to weather the latest troop reduction? The challenges and implications of the reduction are addressed in Part 2 of this series.

John Chen is a research intern at the National Defense University. The author would like to thank Dr. Phillip C. Saunders, Dr. Joel Wuthnow, David C. Logan, Dennis J. Blasko, and Ken Allen for their invaluable insights and generous assistance. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the official policy or position of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Notes:

- Chinese laws do not appear to specify transfer to the People’s Armed Police (PAP) as a regularly available option for soldiers leaving the PLA, although past reductions have transferred entire PLA units to the PAP. Considering the amount of state media attention surrounding other downsizing methods and goals, such wholesale transfers are unlikely to represent a significant portion of the ongoing force reduction.

- For a seminal treatment of Chinese military discharge policies in the open literature, see Maryanne Kivlehan-Wise, “Demobilization and Resettlement: The Challenge of Downsizing the People’s Liberation Army,” in Civil-Military Relations in Today’s China, David M. Finkelstein and Kristen Gunness. (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2007).

- Maryanne Kivlehan-Wise, “Demobilization and Resettlement,” pp. 260–261.

- Maryanne Kivlehan-Wise, “Demobilization and Resettlement,” p. 262.

- The term cadre [干部] includes both military officers and PLA civilians [wenzhi ganbu; 文职干部]. The more specific Chinese term for “officer” is junguan [军官], but PLA military discharge regulations tend to use jundui ganbu [军队干部] in reference to officers. This article uses “officers” to refer to both uniformed military officers and PLA civilians.

- See also Maryanne Kivlehan-Wise, “Demobilization and Resettlement,” pp. 263–266.

- See Figure 2 for more detail.

- See Figure 2 for more detail.

- Maryanne Kivlehan-Wise, “Demobilization and Resettlement,” p. 260.

- Ken Allen notes that the PLA has allocated money for improved off-base housing, and reports that corps deputy-leader grade officers and up are allowed to keep their on-base housing after separation from the PLA.

- Kivlehan-Wise cites anecdotal evidence documenting this trend, which likely applies to rural conscripts more than those from the cities. See Maryanne Kivlehan-Wise, “Demobilization and Resettlement,” p. 268.

- Dennis J. Blasko writes that new recruits are “drawn mostly from a pool of over 10 million males that reach conscription age annually,” suggesting that conscript supply still outnumbers demand. See Dennis J. Blasko, The Chinese Army Today, (New York, NY: Routledge, 2012), p. 59.