Influence of Central Asian Islamic Radicals on the Situation in the North Caucasus

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 9 Issue: 148

By:

A multitude of rumors and speculation exists about the connection between Islamic radicals from Central Asia and the North Caucasus. The following will seek to separate rumor from reality, while analyzing the breadth, scope and policy consequences of these links.

There are, first of all, historical legacies that explain continued contacts between Central Asian and North Caucasian Islamic radicals. In 1944, Josef Stalin deported North Caucasus ethnic groups (Chechens, Ingush, Karachais and Balkars) precisely to Central Asia (mostly Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan). When Nikita Khrushchev allowed the repressed peoples to return home, some Chechens, Ingush, Karachais and Balkars remained in Central Asia, and these familial and relational ties between the two regions remain to this day (Igor Rotar, “Under the Green Banner: Islamic Radicals in Russia and the Former Soviet Union,” Religion, State & Society 30(2), June 2002).

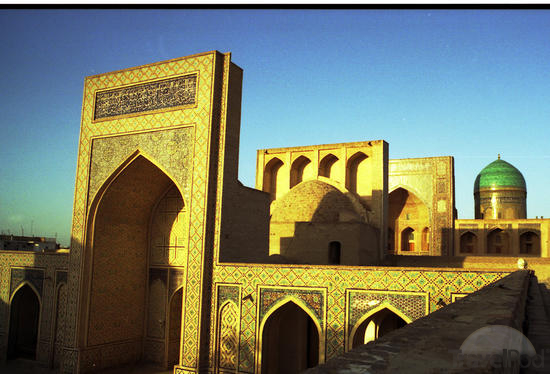

Past direct religious links also played a part in shaping the present condition. Notably, only one Islamic university existed within the Soviet Union: the Madrasa Mir-Arab in the city of Bukhara in Uzbekistan, and many North Caucasian imams studied there. In addition, many underground madrasas existed at the beginning of “perestroika” in the Uzbek city of Namangan, where the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) was established. A large number of future Chechen field commanders, for example, the former Chechen field commander Salman Raduev, reportedly studied at these madrasas (Igor Rotar, “Under the Green Banner: Islamic Radicals in Russia and the Former Soviet Union,” Religion, State & Society 30(2), June 2002). “Chechens are devout believers. But their religious education is weak. Islamic scholarship in Central Asia is much stronger than in the North Caucasus. So, many ideologists of the Chechen independence [movement] studied in Central Asia,” one of leaders of Tajikistan’s opposition, Akbar Turadjonzoda, told Jamestown in 1996.

There were thus clear preconditions for the union of Islamic radicals from the North Caucasus and Central Asia in the 1990s. As the situation in Chechnya continued to spiral toward the first war (1994-1996), a connecting link between the North Caucasus and Central Asian Islamic radicals soon became personified in the famous Chechen War Lord Emir Khattab, originally a citizen of Saudi Arabia. In 1993-1994, Khattab trained fighters from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in Afghanistan. On July 13, 1993, Khattab participated in an attack on border outpost no.12, “Sorigor,” on the Tajikistan-Afghanistan border (Caucasian Knot, July 29, 2010).

By 1996, however, Khattab established a military training camp in Chechnya, the “Uzbek Front,” for fighters from Uzbekistan. One of the leaders of the IMU, Bahrom Abdulaev, met with Khattab in Chechnya and discussed the training of Uzbek fighters. As a result of this deal, reportedly about 300 Uzbek militants were trained at Khattab’s military camp in Chechnya (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, August 24, 2000). But these figures may be overstated; Russian and Uzbekistani authorities have officially named fewer than ten citizens of Uzbekistan who had fought in Chechnya. “Of course, during the 1990s there was some collaboration between Central Asian and North Caucasian Islamic radicals, but the scale of this cooperation was not large. The Russia media often wrote about the 300 Uzbek militants in Chechnya, but I do not believe this figure,” cautioned Dr. Aleksey Malashenko, a leading researcher at the Moscow branch of the Carnegie Center, in an interview with Jamestown on July 24. “I suppose that the real quantity of Uzbek militants in Chechnya is ten times smaller,” he concluded.

The current leader of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, managed to slow down the activity of rebels in Chechnya. The tensest situation in the North Caucasus is currently in Dagestan. Consequently, most foreign volunteers who want to help the rebellion come to Dagestan. “Definitely, most Islamic radicals from abroad, who want to fight in the North Caucasus, come to our republic. I did not hear about any Uzbek or Tajik rebels in Dagestan. But at least seven Kazakh fighters were killed and four arrested in Dagestan between 2009 and 2011,” Dr. Eduard Urazaev said in an interview with Jamestown on July 23. Dr. Urazaev is a former minister of ethnic affairs of Dagestan, a deputy director of the Dagestan Department of Information, and a well-known political scientist. “I suppose that our Islamic radicals established a recruitment network in this republic,” he added.

Dr. Alexander Knyazev, an Almaty-based coordinator of the Central Asia and Caucasus program at the Russian Institute of Oriental Studies, agrees that Central Asian Islamic militants who come to fight in the North Caucasus are presently more likely to originate from Kazakhstan than from any of the other Central Asian republics. “From an economic point of view, Western Kazakhstan has more connections with the Caucasus than with other parts of Kazakhstan. For example, most goods coming across the Caspian Sea to the region originate from the Russian Caucasus,” he told Jamestown on July 25. “In addition, there is a large Caucasus diaspora in Western Kazakhstan. So, it is not surprising that North Caucasian and Central Asian Islamic radicals have solid connections,” he noted.

However, Dr. Eduard Urazaev admits that the scale of help the North Caucasus rebels receive from Kazakhstan should not be overestimated. “A few dozen fighters from Central Asia are negligible for our scale [of insurgency in Dagestan]. In addition, the discovered fighters from Kazakhstan are not educated believers; they are ordinary marginal persons. So, I do not think that the help is a serious business,” Dr. Urazaev told Jamestown on July 23.

Despite the large potential for a closer union of Central Asian and North Caucasian Islamic radicals, the dissociation between individual ethnic groups has turned out to be a much stronger factor than pan-Islamic solidarity. The Islamic radicals have tried to overcome the inter-ethnic cleavages, and they gained some limited success. “But ethnic identity still remain a more important factor than [a common] religious identity,” Dr. Malashenko argues.