Injecting Russian Gas Into TAP: Downgrading Importance of Southern Gas Corridor

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 14 Issue: 20

By:

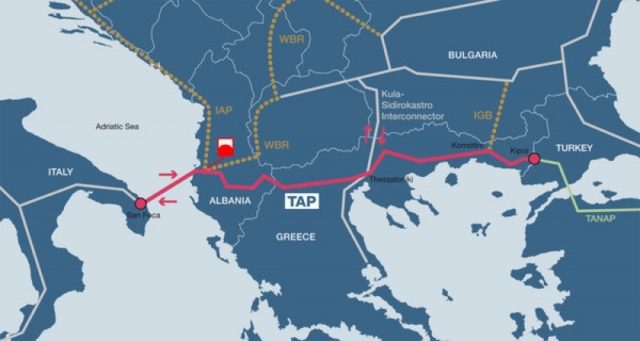

For the first time ever, Gazprom officially expressed interest in using the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) to deliver Russian gas to Europe (Trend, January 24). During the European Gas Conference in Vienna, on January 24, Gazprom deputy CEO Alexander Medvedev said that Russia’s upstream capacity is sufficient to export more than 100 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year of extra gas to Europe, but it faces an infrastructure problem. Since planned capacities of Nord Stream 2 and Turkish Stream will not be large enough to deliver all this to Europe, the company is discussing the possibility of using capacity in the Poseidon pipeline or TAP, Medvedev stated (Natural Gas World, January 24). TAP initially envisages transporting 10 bcm per year of Azerbaijani gas, pumped from the offshore Shah Deniz field, to Europe through Greece, Albania and the Adriatic Sea to Italy.

Commenting on Medvedev’s statement, Lisa Givert, the head of communications for the TAP consortium, said that TAP’s commitment to transporting Shah Deniz II gas was underpinned by a 25-year-long gas transportation agreement. The pipeline was designed with the option to expand capacity to 20 bcm per year, when extra gas volumes come on stream with the construction of additional compressor stations along the route. Moreover, in line with the consortium’s regulatory obligations, the pipeline can offer its expanded capacity to third parties based on an “open season.” According to Spain’s Enagas (a TAP shareholder), if any third-party gas-shipper requests transportation capacity in TAP during the “open season” and complies with the regulatory framework, TAP can provide capacity to it. Italy’s Snam (another TAP shareholder) said that “Gazprom’s joining TAP will double its capacity. TAP’s capacity can be increased up to 20 bcm with a small investment, which will be cheaper than [rival pipeline] Poseidon’s expansion” (Natural Gas World, January 26; Neftegaz.ru, January 25; Trend, January 25, 26, February 2).

Gulmira Rzayeva, a principal research fellow at the Baku-based Center for Strategic Studies, commented that it would be technically possible for Gazprom to pump Russian natural gas through the planned Turkish Stream pipeline and connect to TAP on the Turkish-Greek border. This route would then allow Gazprom to transport its gas to Greece and other southern European markets while bypassing the transit route across Ukraine. When the capacity of the pipeline is increased from 10 bcm to 20 bcm per annum, any company wishing to transport its gas through TAP (whether Gazprom or another company) can book certain volumes in the pipeline via an “open season” formula, according to European legislation, argued Rzayeva (1news.az, January 25). According to Agnia Grigas, a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, in Washington, DC, Russia’s desire to use TAP contradicts the original purpose of the project, which is to diversify sources of Europe’s natural gas away from Russia. “There were hopes that TAP would be filled not only with Azerbaijani gas, but also with Turkmen gas in the future. Moscow seeks to be the one that fills TAP’s capacity,” Grigas argued (Trend, January 31).

Theoretically, if Russia were to pump natural gas to the Turkish-Greek border via the proposed Turkish Stream pipeline, and from there, deliver this gas to European markets via TAP, such an arrangement would not breach the European Union’s Third Energy package rules. The EU Commission’s regulation explicitly mandates that 50 percent of TAP’s total/final capacity be open for third party access (TPA) after expanding the pipeline. When TAP’s capacity is doubled to 20 bcm per year, Russia, in accordance with this EU regulation, could, therefore, request that the TAP Consortium construct additional entry/exit points for compressors in Greece. Gazprom could then reserve space in the pipeline by requesting TPA to transport its gas via TAP (Cijournal.az, January 10). Moreover, in 2016, BP signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Rosneft to purchase of 7–20 bcm per year of Russian gas. The volume is more/less equal to potential Azerbaijani gas supplies (10–20 bcm annually) to Europe as of 2020, within the Shah Deniz Project, in which BP is the development operator (Abc.az, January 26).

However, the Shah Deniz Consortium has already secured 100 percent of TAP’s initial capacity of 10 bcm per year for Azerbaijani gas with a 25-year contract and with a TPA exemption from the EU for the first stage of gas delivery. This means that Russian gas cannot be transported via TAP for at least the next 25 years, unless there are either significant market or geopolitical changes, or sufficient gas demand/shortage to drive expansion up. The Shah Deniz Consortium’s long-term contracts, together with the relevant EU legislations, make this option unlikely, however. Moreover, TAP’s expansion would enable Gazprom to deliver a maximum of 10 bcm per year through the pipeline, while Turkish Stream’s planned second string is designed to pump 15.75 bcm annually (Cijournal.az, January 10).

Russian gas flow through TAP would be a strong blow to the United States’ political investments in the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), which is supposed to lessen Europe’s gas dependence on Moscow. Amos Hochstein, the US special envoy for energy affairs, recently reiterated Washington’s full support for the SGC’s successful implementation, despite the political changes in Europe and the US. The “SGC is important not only for Azerbaijan, but also critical for energy and political security of Europe” as a means to overcome the threat of energy monopolies on the continent, said Hochstein (Trend, December 15, 2016). And at the 2017 Athens Energy Forum, US Ambassador Geoffrey Pyatt stated that it was necessary to protect “[SGC-related] projects against other proposed schemes which threaten the future of Europe’s energy security” and those that “would exacerbate European dependency on Russian gas” (Athens.usembassy.gov, February 1).

Russia’s decision to benefit from TAP means perspectives for the Interconnector Turkey–Greece–Italy (ITGI)/Poseidon, which was previously planned as an extension of Turkish Stream, is still under question, and other options seem unlikely to succeed (see EDM, August 2, 2016). However, the injection of Russian gas into TAP could create a rivalry between Russian and Azerbaijani gas in terms of volume and market share. Given the possible expansion of both TAP (from 10 to 20 bcm per year) and the SGC link Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP—from 16 to 23/31 bcm annually), Russian gas could block the perspective for additional volumes from Azerbaijan’s expected gas fields (including alternative sources from Turkmenistan, Iran, Iraq or the Mediterranean). With its current gas potential, Russian Gazprom would be in a position to be the first to supply additional gas TAP once it expands its capacity. Such an outcome would downgrade the importance of the SGC in the context of the EU’s energy diversification plans.