Modernizing Military Intelligence: Playing Catchup (Part Two)

Publication: China Brief Volume: 16 Issue: 19

By:

This two-part series is adapted from remarks delivered at The Jamestown Foundation’s Sixth Annual China Defense and Security Conference and chapter in China’s Evolving Military Strategy (2016). Part One addresses the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) evolving thinking on intelligence. Part Two addresses the organizational aspects of how the PLA’s intelligence evolved away from military operations and how this problem is being addressed under the current reform program.

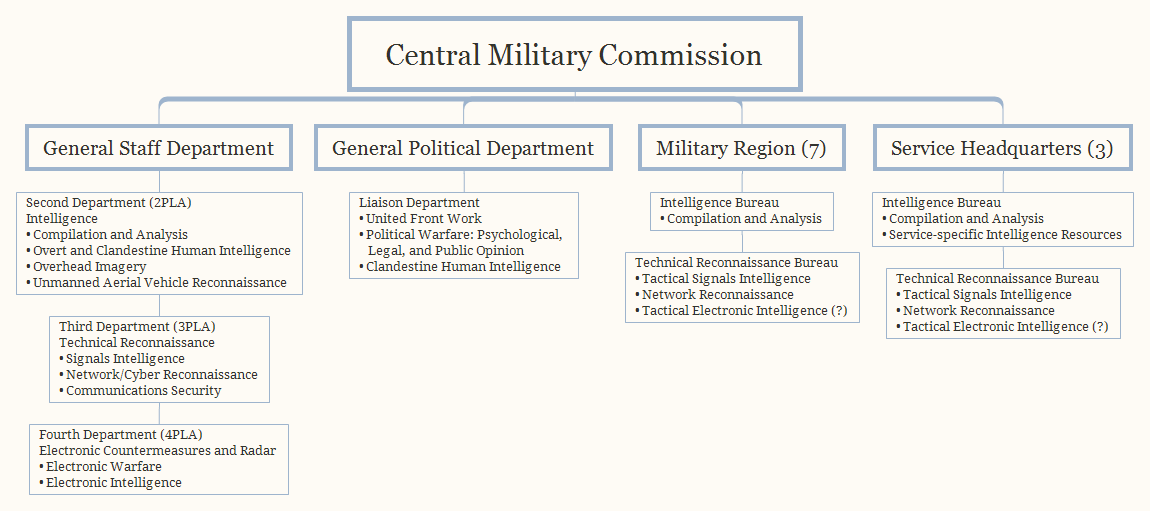

In the early 2000s, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) outlined an expansive set of intelligence missions that the military’s intelligence organizations were ill-prepared to execute. PLA intelligence needed to be able to support operational decision-making at all levels, support deterrence operations, and guide information warfare in the network, electro-magnetic, and psychological domains (China Brief, December 5). The military intelligence apparatus centered in the General Staff Department, however, had been allowed to drift. After the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) military intelligence took on new responsibilities in support of Party rather than military leadership because of its unique capabilities and the dissolution of civilian intelligence bureaucracies. Although the PLA slowly began to reassert itself over its principal intelligence departments through personnel appointments beginning in December 2005, PLA intelligence and warfighting concepts only started to align during the latest round of reforms (China Brief, November 5, 2012).

Reforming the PLA’s intelligence apparatus to meet modern demands required two significant adjustments. The first related to personnel and ensuring that intelligence officers understood the operations they supported. Chinese military intelligence filled the vacuum created by the dissolution of civilian intelligence agencies in the early years of the Cultural Revolution. Deng Xiaoping’s rise in the late 1970s cemented their role, because of his long-standing relationships in the PLA and his distrust of the party’s security services. The rise of the defense attachés without operational experience, who dominated military intelligence from 1988 to 2005, was a symptom of this shift away from military operations. The second related to organization and ensuring more rational management of intelligence resources. The creation of the Strategic Support Force following the reforms announced by Xi Jinping on November 26, 2015 appears to have reorganized intelligence along the lines suggested in the CMC’s opinion: “the CMC leads, the theater commands fight, and the services equip (军委管总、战区主战、军种主建)” (Xinhua, January 1). Although the full implications of the PLA’s efforts to reform intelligence are not yet clear, its intelligence apparatus is finally beginning to catchup with the rest of the military.

How the PLA Lost Its Intelligence Apparatus

The PLA’s intelligence apparatus slowly drifted from military control beginning in the late 1960s as it became the principal intelligence provider to the central leadership. A series of reinforcing developments limited the PLA’s control over its intelligence apparatus and prevented military intelligence from evolving alongside the rest of the PLA as the military moved toward “system-of-systems” operations beginning in the 1990s.

Intelligence services operate within a larger national context that places additional demands on their members beyond their own chain of command. Regardless of whether intelligence services are national or departmental, their capabilities to collect and analyze intelligence are national resources that can be called upon by national leadership as desired. From 1966 through at least 1976, the PLA’s intelligence organizations were among the only functioning services that could support the Party leadership. The turmoil caused by the Cultural Revolution led to the dissolution of the Central Investigation Department and the Ministry of Public Security’s foreign intelligence units. Those in any kind of routine contact with foreigners often faced espionage accusations, and the tight compartmentalization with which sources were handled ensured that few if any other officers could vouch for or defend those accused. As the state ministries and the Party bureaucracy shut down, the civilian intelligence organizations appear to have turned their sources and operations over to military intelligence. [1]

The intelligence leadership within the General Staff Department (GSD) also underwent a generational turnover that privileged the general foreign affairs expertise of defense attachés over expertise gained through operations or providing direct intelligence support to PLA commanders. These officers were exemplified by Xiong Guangkai (熊光楷), who served tours in East and West Germany as a defense attaché. Xiong served as deputy director and then director of 2PLA (1984–1988 and 1988–1992, respectively) before becoming the deputy chief of the general staff responsible for overseeing intelligence and foreign affairs from 1998 to 2005. [2] Prior to Xiong’s rise to the top of 2PLA, the department’s chiefs had operational intelligence experience in combat during the Chinese Revolution, War of Resistance against Japan, or the Korean War. From Xiong’s directorship onward, however, only one of the seven 2PLA directors, Chen Xiaogong (陈小工), had any combat or operational experience. [3]

The centrality of military intelligence remained even after the Cultural Revolution and the reestablishment of party-state intelligence functions in a briefly reconstituted Central Investigation Department and, in 1983, the Ministry of State Security (MSS). Several reasons account for the PLA’s overall importance to Chinese policymakers. First, the PLA possesses the only all-source intelligence capability within the Chinese system, and there is no reason to believe intelligence is shared across the divide between the civilian ministries and the PLA on a routine basis. Shared operational platforms suggest the civilian and military intelligence services share intelligence at the working level in areas such as Taiwan or anti-Falungong operations. The need to keep building new intra-governmental centers for security operations, however, suggests intelligence is not routinely integrated (China Brief, January 25; China Brief, December 5, 2014; China Brief, September 16, 2011). Second, the senior-most PLA intelligence officer, who up until the recent reorganization was a GSD deputy, sits on the leading small groups (LSG) that guide foreign and security policy, such as the Foreign Affairs and the Taiwan Affairs LSGs. The MSS would not join the Foreign Affairs LSG until the mid-1990s, more than twelve years after the MSS was formed. Third, in 1985, Deng Xiaoping placed draconian restrictions on the MSS that reduced its presence in China’s embassies and ability to recruit sources abroad. These constraints were not lifted until at least the 2000s (The National Interest, July 6, 2015). Despite having its own presence in the embassies and other official platforms like Xinhua, the PLA was not subject these restrictions.

Personal relationships also helped isolate the PLA intelligence apparatus from military’s direct control. From Deng Xiaoping’s rehabilitation as GSD chief in 1975 to Xiong’s ascension to GSD deputy in 1998, the intelligence leadership were all veterans of the 8th Route Army with a direct personal connection to Deng. These close personal ties and relaxed operational restrictions suggest Deng was comfortable relying on the PLA for his intelligence needs. [4] The close relationship between General Secretary Jiang Zemin and Xiong also boosted the centrality of military intelligence and probably cemented the drift between the PLA’s operational arms and its intelligence apparatus. Reportedly, this relationship was close enough that Jiang attempted to install Xiong at the MSS to assert control and boost the ministry’s intelligence collection against Taiwan (South China Morning Post, March 17, 1998). Other rumors suggest Xiong turned PLA signals intelligence and other intelligence capabilities on the PLA leadership to help Jiang outmaneuver the military bureaucracy in implementing de-commercialization and oversee day-to-day management of the PLA.

These factors held back the PLA’s intelligence apparatus from adapting to the changing requirements for intelligence work within an informatizing military. After the retirement of Xiong in December 2005, however, the PLA slowly began reasserting control over military intelligence. The changes began at the leadership level, where senior intelligence leaders now had the opportunity for promotion or lateral moves into operational roles as deputy commanders. Intelligence stars like Chen, Yang Hui (杨辉), and Wu Guohua (吴国华), who might have retired early in view of their terminal career prospects, moved to the PLA Air Force, Nanjing Military Region, and Second Artillery, respectively. The GSD deputy chiefs after Xiong all came from operational backgrounds, such as former GSD Operations Department chief Zhang Qingsheng (章沁生) and former pilot and now PLA Air Force Commander Ma Xiaotian (马晓天) (China Brief, November 5, 2012). Anecdotal evidence also has started to emerge that such interchanges between operations and intelligence personnel are occurring at lower levels, giving some officers time abroad in military attaché billets and moving mid-career intelligence officers into deputy unit commander billets.

Reforming the Military, Reforming Intelligence

On November 26, 2015, CMC Chairman Xi Jinping announced far-reaching military reforms to reshape and reorganize the PLA. Prior structures, such as the military region system, have been erased, and the ground forces, traditionally predominant in every major but ostensibly “joint” PLA department, appear to have lost their position of power (China Brief, December 14, 2012). Amid the propaganda fanfare over new organizational structures, the PLA did not make any announcements that explicitly noted how the military would reorganize intelligence work under the aegis of this extensive reform agenda. A tentative analysis is still feasible, because of how systematically the PLA has organized itself and its intelligence organs.

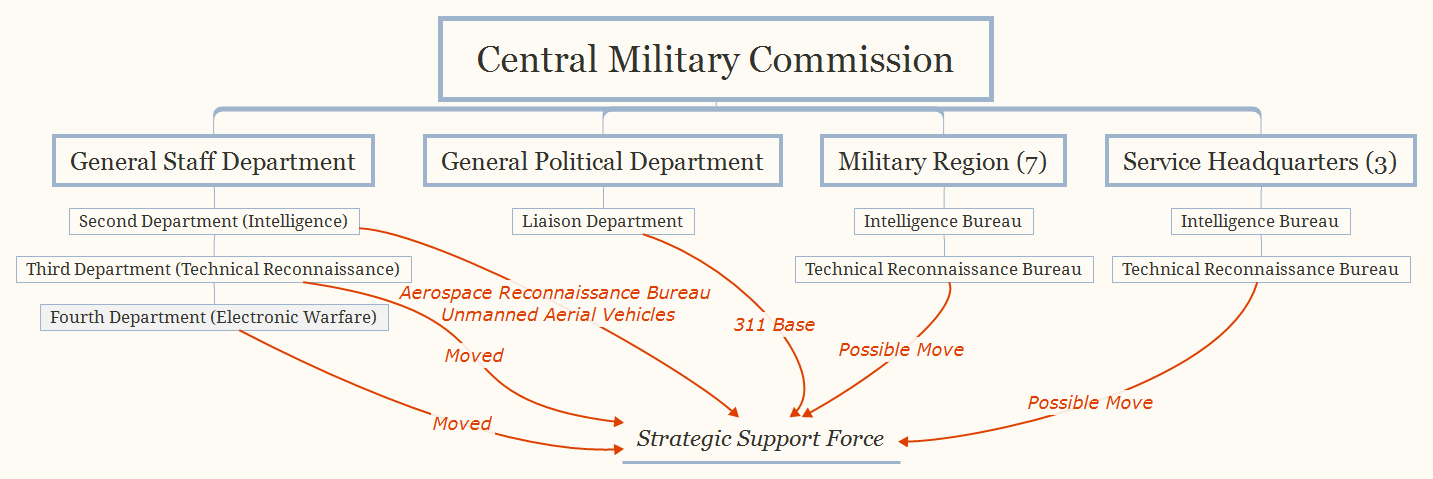

The available Chinese sources suggest that the former General Staff Department’s (GSD) intelligence functions have been divided between three new organizations, the Joint Staff Department (联合参谋部, JSD), the Strategic Support Force (战略支援部队, SSF), and perhaps also the PLA Army leading organ (i.e. national-level headquarters). The structural logic and organizational dynamics associated with these changes allows for certain initial inferences about the future of PLA intelligence. The changes that are known to have occurred thus far indicate that the PLA has seemingly differentiated its technical intelligence and strategic or all-source intelligence capabilities. While elements of the former 2PLA have been elevated to the CMC level under the JSD, the SSF has incorporated the technical reconnaissance capabilities that are directly relevant to offensive operations in space, cyberspace, and the electromagnetic domain.

The Joint Staff Department appears to have inherited from the GSD responsibility for strategic-level intelligence and PLA foreign affairs work, as well as the analytic and human intelligence collection resources, of the former GSD Second Department (2PLA). The JSD reportedly includes a subordinate Intelligence Bureau (情报局) that is most likely a renamed 2PLA, which was known as the Intelligence Department (情报部) (Duowei, April 10; Surging News, August 2). Unofficial sources identify the previous head of 2PLA, Major General Chen Youyi (陈友谊), as chief of the Intelligence Bureau (92to.com, October 27). The GSD deputy chief responsible for intelligence and foreign affairs, Admiral Sun Jianguo (孙建国), is now a JSD deputy chief and continues to represent the PLA to foreign audiences in Beijing and at forums like the Shangri-La Dialogue (Xinhua, June 5; China Military Network, October 12). Sun also still serves as the president of the China Institute for International and Strategic Studies (CIISS), a position with some authority in the military intelligence community. None of the sources describing the JSD organizational structure identifies any bureau within the department that could be the Third Department (3PLA) for signals intelligence or the Fourth Department (4PLA) for electronic warfare.

The Strategic Support Force has incorporated the majority of the technical intelligence capabilities that were previously associated with elements of the GSD’s 2PLA, 3PLA, and 4PLA. The SSF appears to have taken control over certain GSD and also the majority, if not all, of the former General Armaments Department’s (GAD) space-related units, under the aegis of its Aerospace Systems Department (航天系统部) (National Defense Industry Bureau Network, October 21, 2016). Notably, based on personnel movements, the 2PLA’s Aerospace Reconnaissance Bureau appears to have moved over to the SSF, where it may now be known as the Aerospace Reconnaissance Command (PLA Daily, April 9; The Paper, April 9). As a result, the SSF evidently now controls the PLA’s intelligence satellites and space reconnaissance capabilities. There are also indications that the majority of the former 3PLA has been transferred to the SSF, likely to form its Cyber/Network Systems Department (网络系统部). The available evidence includes explicit indications of the new affiliation of former 3PLA institutions, the linkage of the address of the 3PLA headquarters to the SSF, and personnel transfers. [5] For instance, the former 3PLA’s 56th Research Institute and 58th Research Institute are now under the aegis of the SSF (China Postgraduate Admissions Information Network, Undated; China Postgraduate Admissions Information Network, Undated). In addition, 4PLA, with its associated capabilities for electronic support measures, may constitute the core component of the SSF’s electronic warfare mission, given that the 54th Research Institute, which was previously subordinate to 4PLA, has been incorporated into the SSF (bjgtz.com, radars.ie.ac.cn). These developments all are consistent with intelligence support to information warfare as outlined in Part One and the SSF’s leading role for information warfare (China Brief, December 5; China Brief, February 8).

Certain components of the former GSD may also have been transferred to the new Army Leading Organ (陆军领导机构) or Army Staff/Headquarters Department (陆军参谋部). Since the GSD has previously served as both the joint staff for the PLA as a whole and the headquarters for the ground forces, the establishment of an independent, national-level headquarter department for the ground forces is among the most important aspects of the reforms. Previously, the ground forces’ dominance of GSD leadership positions probably skewed most of the staff work toward supporting their operational needs and political desires. The division of the JSD and the ground forces headquarters is intended to allow each to focus on their respective responsibilities. Given this underlying rationale, the split could potentially break up elements of the GSD’s intelligence departments, dividing them between the ground forces and the theater commands. The PLA Army Headquarters Department probably includes at least an intelligence bureau to provide strategic intelligence support to ground forces leadership.

Speculatively, the PLA might divide the former military regions’ intelligence and technical reconnaissance bureaus between the five new theater commands and the SSF. Intelligence is a common headquarters component and a recognized staff function. One of the critical lessons the PLA drew from its experiences during the Chinese Revolution and Civil War was the need to keep intelligence close to decision-makers, and modern PLA writings, as noted in Part One, have emphasized the need for such a close connection (China Brief, December 5). Even if the military region’s collection capabilities were given wholly to the SSF, their intelligence bureaus would probably be reconstituted among the theater commands’ headquarters to process incoming information for the command’s specific needs.

Looking forward, the PLA appears unlikely to resolve the underlying contradiction between the need to centralize information warfare capabilities and the different bureaucratic rice bowls in intelligence work. Intelligence always will be a military staff function, and the JSD should rightfully have a stake in both intelligence capabilities and supporting decision-makers at senior levels. The real question of bureaucratic conflict may lie between the SSF and the Political Work Department (the former General Political Department, GPD).

Although SSF has likely consolidated the majority of the PLA’s information warfare capabilities and forces under a single command structure, the Political Work Department may retain primary responsibility for political/psychological warfare. The former GPD’s Base 311 (Unit 61716), which engages in public opinion warfare, psychological warfare, and legal warfare (i.e., the three warfares), most likely is now part of the SSF, based on personnel transfers. [7] However, the primary department responsible for political warfare, as well as the intelligence-related functions outlined in the Political Work Guidelines, is the former GPD Liaison Department (联络部). This department may now be the Liaison Bureau (联络局) within the new Political Work Department (Sina Blog “Qin City Park”, July 13). The changes to the guidelines in 2003 and 2010 emphasized the importance of political officers becoming part of the PLA’s war-fighting capability. [8] Other publications about modular force groupings within evolving system of systems operations included political/psychological warfare units (China Brief, March 15, 2013). If the Liaison Department (or its successor) does remain within the Political Work Department, then information warfare in its entirety will operate under divided commands that only unify at the CMC level, which may undermine effective coordination.

At this point, the remaining unknowns remain are substantial. For example, as of late 2016, many of the technical reconnaissance bureaus (TRB) for the services and military regions appear to be in existence, but no information published online since the reorganization clearly links them to the services, the new theater commands, or the SSF. The guiding phrase for the reform, “the CMC leads, the theater commands fight, and the services equip” (军委管总、战区主战、军种主建), suggests the TRBs could be transferred to or divided between the SSF or the theater commands. If the services are supposed to focus on equipping their forces, then it seemingly makes less sense for them to possess tactical intelligence collection capabilities.

The construction of an alternative center for intelligence work also raises the question of how the PLA will train the intelligence personnel for the SSF to better support military operations at the tactical level. The traditional intake into the military intelligence services comes from the Nanjing International Relations Institute and the Luoyang Foreign Language Institute, as well as the PLA Information Engineering University. While technical and area studies education may work well for training the personnel from the former 2PLA, 3PLA, and 4PLA, these programs do not translate well into the kind of tactical intelligence support required for targeting and bomb damage assessment. If intelligence is being integrated more broadly to support operations, then new training programs will need to be created under the SSF—a point the PLA appears to recognize (People’s Daily, January 24).

Conclusion

PLA thinking on intelligence has evolved remarkably little over the last fifteen years, because, in many respects, it has not been necessary. The PLA’s steady modernization effort to conduct joint operations on shared knowledge of the battlefield with precision-guided munitions demanded more from the PLA’s intelligence apparatus than it could give without a serious overhaul. The intelligence organizations at the General Staff Department level were ill-suited to provide tactical support, so little in the way of experimentation could be done to develop tactical intelligence doctrine using GSD resources. In a sense, the PLA has not yet seen or tested its thinking about intelligence in any serious way. Though the possibility that intelligence has been tested through exercises cannot be ruled out, there are enough other potential drivers of the current reform drive and the creation of the SSF to view intelligence as an ancillary issue—or only as one part of the broader changes to information operations (China Brief, February 8).

The ambitious set of intelligence missions—supporting decision-making at all levels of command, calibrating deterrence operations, and guiding information warfare—suggests the challenges for PLA intelligence is not in the concepts but the organizational infrastructure to execute. The broad range of intelligence work that goes into these missions requires an equally broad set of training programs that will teach skills that cannot readily transfer from one kind of decision support to another. If the intelligence organizations are centralized, then the new organizations need to be able to reach across the PLA and also tailor its support for the different challenges facing different military units. Moreover, unless the PLA moves away entirely from supporting the Party leadership on foreign affairs, military intelligence also needs to keep officers capable of doing collecting, analyzing, and presenting intelligence to the leadership on foreign countries.

For analysts, the challenge will be identifying the PLA’s evolving intelligence posture and how it resolves the challenges it faces. Chinese security authorities are allowing fewer and fewer slipups as they become accustomed to the ways in which researchers and foreign intelligence services exploit the Internet (China Brief, May 7, 2014). If the PLA reorganization proceeds down some of the aforementioned lines, then many of the unit identifiers will change over. Many of the PLA’s lower-level intelligence bureaus in the services and military regions barely had a public or online footprint, and the lag time in identifying the new units could be months if not years. Moreover, the tools for identifying what is included in military training and education are blunt, especially on a sensitive topic like intelligence. Top-level changes at the level of the JSD and the theater commands; however, the nuts and bolts of making intelligence successful are unlikely to be available.

Peter Mattis is a Fellow in the China Program at The Jamestown Foundation, where he served as editor of the foundation’s China Brief, a biweekly electronic journal on greater China, from 2011 to 2013. He previously worked in the U.S. Government and the National Bureau of Asian Research. Mr. Mattis received his M.A. in Security Studies from Georgetown University and earned B.A.s in Political Science and Asian Studies from the University of Washington in Seattle. He also studied Chinese language, history, and security policy at Tsinghua University in Beijing. He is the author of Analyzing the Chinese Military: A Review Essay and Resource Guide on the People’s Liberation Army (2015).

Elsa Kania is a recent graduate of Harvard College and currently works as an analyst at the Long Term Strategy Group.

Notes

- David Ian Chambers, “Edging in from the Cold: The Past and Present State of Chinese Intelligence Historiography,” Studies in Intelligence 56, No. 3 (September 2012), pp. 31–46.

- Defense Intelligence Agency, “China: Lieutenant General Xiong Guangkai,” Biographic Sketch (Washington, DC, October 1996) Digital National Security Archive.

- Chen Xiaogong served as a unit commander again Vietnam, either in 1979 or in the border skirmishes that flared up most noticeably in 1984. His unit reportedly lost more than 20 percent of its strength, suggesting Chen witnessed serious fighting. See, James Mulvenon, “Chen Xiaogong: A Political Biography,” China Leadership Monitor, No. 22 (Fall 2007).

- Peter Mattis, “PLA Military Intelligence at 90: Continuous Evolution,” Paper presented at Annual CAPS-RAND-NDU Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, November 2015.

- For references to the Aerospace Systems Department, see, for instance: National Defense Industry Bureau Network, October 21, 2016.

- In addition, it is likely that most of the former GSD Fourth Department (4PLA), the Electronic Countermeasures and Radar Department, has also been transferred to the SSF.

- According to articles available through CNKI, Mu Shan(牟珊) was formerly affiliated with Base 311 (61716部队) but, as of mid-2016, was affiliated with the Strategic Support Force.

- See the 2003 Political Work Regulations and 2010 Political Work Regulations.