Ramping the Strait: Quick and Dirty Solutions to Boost Amphibious Lift

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 14

By:

Introduction

The threat of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) using military force to coerce or perhaps launch an amphibious invasion of Taiwan has received significant attention in the past year. Meanwhile, the recent commissioning of the PLA Navy’s first Type-075 amphibious assault ship has further highlighted China’s developing amphibious capabilities (South China Morning Post, May 9). At the same time, the apparent shortage of amphibious lift required to execute large-scale landing operations leaves many wondering whether China is serious about its threats against Taiwan. The U.S. Department of Defense’s 2020 China Military Power Report notes the PLA’s focus on ocean-going amphibious platforms rather than a large fleet of traditional landing ships and craft suggests that a direct beach-assault operation is less likely at the moment (Office of the Secretary of Defense, September 1, 2020).

But the PLA may have other plans for transporting troops and equipment across the Strait: the growing capabilities of its merchant roll on-roll off (RO-RO) ships (CMSI, December 6, 2019). These are vessels equipped with built-in ramps that enable wheeled and tracked cargo to load and offload under their own power. Such ships have the potential to deliver a significant volume of force, providing access to port terminals or other lighterage is available. They do not, however, provide solutions for launching waves of amphibious assault forces, for which dedicated landing ships are still lacking. Among the numerous critical components necessary for a successful cross-Strait landing, a failure to secure landing areas for follow-on forces in the initial assault would bring the entire endeavor to a screeching halt, likely inflicting severe costs on the part of the aggressor and resulting in a withdrawal.

For China’s RO-RO ships to support an amphibious assault scenario, their ramps would need to be capable of in-water operations to launch amphibious combat vehicles. This capability appears to have been publicly demonstrated in the summer of 2020 by the PRC-flagged vessel Bang Chui Dao (棒棰岛), a 15,560-ton RO-RO owned and operated by COSCO Shipping Ferry Company (COSCO Shipping Ferry, accessed June 24). This article describes a new ramp system observed on this ship during a recent exercise and discusses its implications for PLA amphibious capabilities in a cross-Strait landing.

New Ramp System Demonstrated in Amphibious Landing Exercises

During the peak of summer training in 2020, the 1st Marine Brigade of the PLA Navy Marine Corps (PLANMC) mustered all personnel and equipment (全员, 全装, quan yuan, quan zhuang) for day and night landing exercises in amphibious training areas off the coast of Guangdong Province. These exercises featured night-time mobilization and assembly, embarkation, obstacle clearance, amphibious assault landings, and artillery and air defense training (js7tv.cn, August 2, 2020). They also included the use of a new ship to carry these forces to their training area.

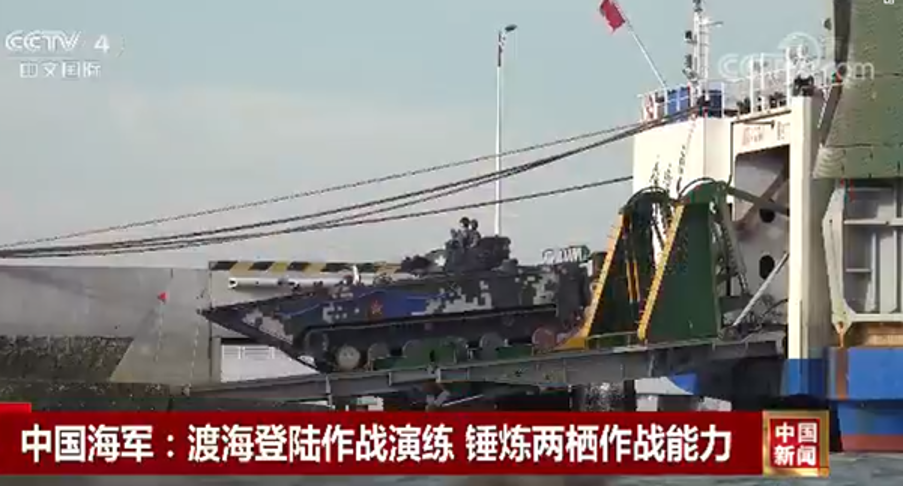

On July 10, the Bang Chui Dao, which usually runs ferry routes across the Yellow Sea and Bohai Gulf, arrived in Zhanjiang (湛江) to join the PLANMC exercise. It took on 1st Brigade troops, trucks, and Type-05 amphibious armored vehicles at the Southern Theater Navy’s 6th Landing Ship Flotilla loading dock (CCTV, August 3, 2020). According to automatic identification system (AIS) transmission data of the vessel’s movements, the ship departed Zhanjiang just before 10:00 AM local time and arrived off Tangxia (塘霞), an amphibious training area in Dianbai County (电白区), at almost 4:00 PM. AIS data indicates that it likely began launching vehicles 4 to 5 kilometers (2.5 to 3.1 miles) offshore without dropping anchor. Video of a vehicle launching shows the ship was likely running slow into the wind to maintain a lee astern; it appears to have maintained bare steerage while drifting to the southeast at half a knot until offloading was completed and then departed for nearby Shuidong Harbor at around 4:48 PM.[1] After being moored dockside overnight and well into the next day, the ship then left for the Shuidong anchorage on the evening of July 11. It returned to Zhanjiang in the afternoon of July 12, presumably to offload PLANMC forces. Although it is unclear how many PLAN landing ships took part, at least one Type-073A landing ship likely participated (CCTV, August 3, 2020).

The ship’s participation is not abnormal. It has supported PLA transportation exercises for years, for example in 2014 (shown below). According to its AIS transmissions, the Bang Chui Dao was very busy in the summer of 2020. It made multiple trips beyond the Bohai/Yellow Sea to areas with PLA landing ships and craft, including a visit to a PLA Ground Forces (PLAGF) watercraft site in Xiamen, Fujian Province which is close to a PLAGF amphibious brigade in Zhangzhou (漳州), and possibly conducted activities in waters near Kinmen (金门, Jinmen) Island.[2] Little information is available on what it did there. Bang Chui Dao also played a significant role in “Eastern Transportation-Projection 2020A” (东部运投-2020A), an exercise held by the PLA Joint Logistics Support Force in the Eastern Theater Command between June and August 2020.

The key technical development demonstrated in its July 2020 exercise with the PLANMC is the converted stern ramp installed on the Bang Chui Dao. The ship’s previous straight stern ramp (shown above) was a hydraulic-powered ramp type often seen on RO-ROs. At some point in the past few years, this vessel’s stern ramp was converted to enable amphibious launch. Video of this capability appeared during a 2019 state media profile of an officer at the former Nanjing Military Region Military Representative Office for Navigational Matters, showing the vessel’s ability to recover a ZTD-05 amphibious assault vehicle, likely from a PLAGF amphibious unit (CCTV-Military Report, May 14, 2019).

The 2020 exercise provides a closer look at the new ramp system. The ramp is driven directly by two large hydraulic cylinders and two support arms. When conducting launch and recovery, these are connected between the top of the hydraulic mounting assemblies on the inner ramp and the top of the freight deck threshold to provide the strength and leverage required to deploy the ramp into the water and withstand sea action. The support arms also act as preventers at maximum extension, while the ramp is kept rigid by the hydraulic cylinders. A longer outer ramp flap has also been added, controlled by another set of hydraulic cylinders mounted on the underside or backside of the ramp. These help to provide strength at the end of the outer ramp and may also allow for further articulation to help vehicles get on the inner ramp. Based on 2020 video footage, the ramp system appears able to launch and recover at a minimum the lightweight ZTD-05 vehicle (26 tons).[3]

Implications

The use of ramps at sea is fraught with challenges. Unsecured ramps run the risk of being snapped off by dynamic stress caused by ocean swells. The introduction of this system suggests confidence by Chinese engineers and the vessel’s operators that their system can work. The combined use of hydraulic systems and support arms means that this new ramp is better situated to handle light sea states, perhaps up to sea state three (based on a scale from one to ten). With converted stern ramps, ships could simply anchor during discharge using the vessel’s own lee. If currents complicate matters, ships might also run at bare steerage speed to ensure smooth vehicle launching. The two training examples that involved the new ramp’s use appear to have taken place in calm conditions. They would likely encounter harsh marine conditions in the Taiwan Strait, which experiences annual average wave heights from 3.6 to 8.5 feet (i.e., light to moderate sea states).[4]

Built in the Netherlands in 1995, the Bang Chui Dao is smaller than some of the RO-RO ships recently built in the Bohai Gulf area. It did not implement national defense requirements during construction but has clearly undergone some amount of modification to better support the PLA. According to the COSCO Shipping Ferry website, the Bang Chui Dao can carry 1,200 passengers and has 835 meters (2,740 feet) of vehicle lane capacity in its main and lower vehicle decks (COSCO Shipping Ferry, accessed June 24). It is difficult to determine the total number of Type-05 vehicles and equipment that could be transported without the dimensions and number of vehicle lanes available. But accounting for a Type-05 chassis length of 9.5 meters (31.2 feet) and fore and aft spacing of 1.5 meters (4.9 feet) between vehicles, as reported by PLA sources, the Bang Chui Dao may theoretically be able to transport up to an amphibious mechanized infantry battalion.[5] This rough calculation does not factor in numerous other considerations that go into load planning.

Thus far, the new ramp system has only been seen on the Bang Chui Dao, but it could be installed across China’s fleet of RO-RO ships. In 2019, authors from the PLA Military Transportation University stated that there were 63 RO-RO ships suitable for use in transporting military units, totaling 140,000 deadweight tons.[6] While larger, more advanced RO-RO ships have been delivered, numerous existing ships still use straight stern ramps like the Bang Chui Dao.[7] Many of these might be good candidates for ramp conversion.

A surge in PLA landing ship construction would be expected before serious preparations for a cross-Strait invasion. This would be exposed to ship spotters and overhead imagery over the course of many months and has not yet been observed. Nevertheless, the testing of new ramp systems as seen on the Bang Chui Dao could offer the PLA a potentially fast and cheap method of surging amphibious lift capabilities without raising concerns. This middle ground scenario raises questions about how quickly such conversions could be detected. Converted RO-RO ships could also be loaded with amphibious combat units well ahead of a planned invasion, supporting personnel with shipboard amenities normally used for civilian purposes. This could help ease pressure on mobilization, embarkation, and movement timelines and could be done at optimal periods, such as nights with low visibility or days with ample cloud cover.

Conclusion

The July 2020 exercise could simply be early testing of the new ramp. There is not enough evidence on its performance beyond short clips showing a few vehicles in operation, leaving one to wonder about its breakdown rate. Nonetheless, the fact that PLA units have used this system during amphibious training, coupled with the necessary costs borne in conversion and training, lends some credibility toward its future use in a military scenario. Due to the associated costs, it is unlikely that commercial ferry operators would want this complicated system installed for regular use. If it is adopted on a larger scale, the PLA would only need as many converted RO-ROs as necessary to fill in the gaps in amphibious lift for surface amphibious assault units. Other larger RO-RO ships could focus on the transport and debarkation of follow-on forces, another uniquely difficult challenge in amphibious assault scenarios that is not addressed here.

Although ramps are nowhere nearly as flashy as footage of the PLAN’s brand-new amphibious assault ships, military observers would do well to watch how many of China’s older and smaller RO-RO ships receive this new ramp system in the coming years.

Special thanks to Captain Patrick Kennedy Sr., Merchant Marine, for his assistance in reviewing the more technical aspects presented in this article. Any mistakes or errors in this article are solely the author’s own.

Conor Kennedy is a research associate in the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute in Rhode Island.

Notes

[1] While no wheel wash is shown in the brief clip, Marine Traffic AIS data suggests the vessel may have run slow into a 23-knot wind out of the north-northeast on a 16-degree heading to maintain position and a lee for ramp operations. Marine Traffic, Date: July 10, 2020 – Past Track of Bang Chui Dao.

[2] AIS data for this analysis was pulled from Marine Traffic, July – September, 2020 – Past Track of Bang Chui Dao.

[3] This is compared to the US Marine Corps new amphibious combat vehicle that weighs approximately 35-tons.

[4] For source on average wave heights in the Taiwan Strait, see: 张桂湘, 张健, 张敏健 [Zhang Guixiang, Zhang Jian, Zhang Minjian], 两岸通航适用客滚船主尺度及适航性分析 [“Cross-Strait Ro/Pax Principal Dimensions and Navigability Analysis”], 船舶与海洋工程 [Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering], No. 6, 2015, p. 2.

[5] For source on vehicle spacing, see: 陈益平 [Chen Yiping], 军用车辆船舶滚装运输有关问题研究 [“Research into the Ro-Ro Transportation of Military Vehicles”], 国防交通工程与技术 [Traffic Engineering and Technology for National Defense], No. 5, 2018, p. 5.

[6] 李鹏, 孙浩, 赵喜庆 [Li Peng, Sun Hao, Zhao Xiqing], 国家战略投送能力发展对合成部队建设的影响与对策 [“Impact of National Strategic Delivery Capability Development on Construction of Synthetic Forces and Countermeasures”], 军事交通学院学报 [Journal of Military Transportation University], no. 8 (2019), p. 3.[7] 赵俊国, 刘宝新 [Zhao Junguo, Liu Baoxin], 艉直式跳板滚装船丁靠直立式码头装卸载保障 [“Loading and Unloading Support of RO-RO Ship with Straight Stern Type Springboard T-Type Berthing at Vertical Wharf”], 水运工程 [Port & Waterway Engineering], No. 6, 2017, p. 77.