The Future of Chinese Foreign Economic Policy Will Challenge U.S. Interests, Part 1: The Belt-and-Road Initiative and the Middle Income Trap

Publication: China Brief Volume: 20 Issue: 2

By:

Editor’s Note: This is the first part of a two-part article that addresses the ways in which the evolution of China’s internationally-focused economic policies are likely to impact—and in many instances, to clash with—the economic policies and interests of the United States. This first part focuses on the policies surrounding the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s worldwide program of infrastructure construction; and on the policies that Chinese leaders are likely to adopt as they seek to avoid the “middle-income trap” of stagnating economic growth. The second part, to appear in our next issue, will examine China’s efforts to advance usage of the renminbi as an international currency, and to seek a greater role in economic institutions traditionally led by the United States and its European allies.

Introduction

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping and other senior CCP leaders have prudently planned for the slowing economic growth that China now faces. CCP officials plan to transition China from its current export-led growth model to one driven by indigenous innovation, and one in which China’s rising global prominence confers to it many of the same advantages traditionally enjoyed by the United States (such as low borrowing costs and influence within international institutions). Although U.S.-China relations have become further fraught amid the trade war, many prominent China hands nevertheless assert that Beijing’s long-term economic plans do not run counter to U.S. strategic interests. [1] However, many of China’s planned foreign economic initiatives—to include the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), global value chain advancement, and renminbi (RMB) internationalization—will come at U.S. expense. Policymakers in both Washington and Beijing should accordingly expect U.S.-China tensions to persist beyond the Trump administration.

China’s need for new growth vehicles is twofold: its economic size has not translated into global influence, and its current economic model is losing steam. First, China’s transformation into the world’s second-largest economy has yet to yield equivalent influence in the international system. Beijing’s sway in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), for example, lag behind China’s status as the largest trade partner and foreign investor for much of the world. The United States, by contrast, has leveraged its economic status to maintain effective control of the Bretton-Woods institutions, to obtain low borrowing costs, and to exercise punishing sanctions programs against unfriendly governments.

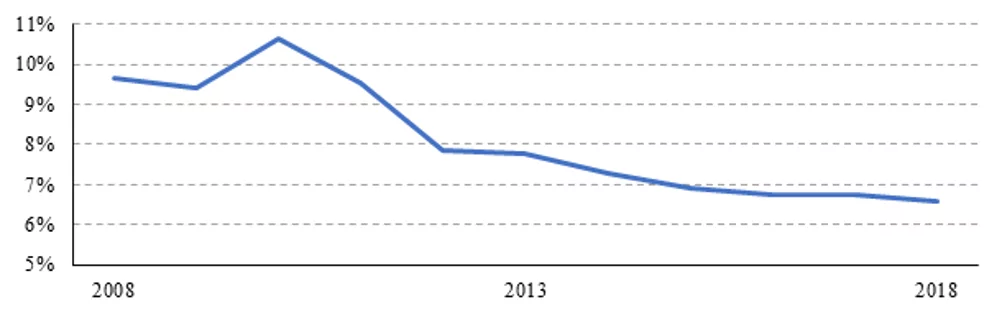

Second, Chinese growth has seen a secular decline over the last decade (see figure 1). The official projected GDP growth rate for 2020 is 6.1 percent (Xinhua, November 30, 2019), but some Chinese officials have hinted that they expect lower sub-6 percent growth in 2020 (South China Morning Post, November 14, 2019). This is a noteworthy signal, for CCP discourse has previously identified the benchmark of 6 percent GDP growth as necessary to avoid social unrest (China Brief, March 22, 2019).

Figure 1. Chinese Annual GDP Growth (2008-2018)

China Faces the “Middle-Income Trap”

The trade war bears some responsibility for the recent economic slowdown, but the decade-long decline suggests that China risks falling into the “middle-income trap,” in which emerging economies lose their competitive edge in manufactured-good exports without entering high-value-add segments of the global economy. China has likely exhausted the growth potential that physical capital and labor can provide in manufactured goods. Further, low capital efficiency prevents China from competing in high-value sectors. Chinese capital investments produce less output compared to other countries, particularly developed ones (Caixin, November 20, 2017).

This inefficiency leads to poorer economic performance as Beijing funnels savings into state-directed firms in an opaque and inefficient manner, thereby misallocating massive sums of investment. China’s lack of a market economy, which would otherwise shut down unproductive firms and expand efficient ones, exacerbates this problem. Beijing could inject even more capital into state firms to stimulate growth—and indeed, the People’s Bank of China moved in this direction at the beginning of 2020 by cutting reserve requirements for Chinese banks (PBOC, January 6). However, this strategy will likely prove to be a short-term fix that increases inflation and labor costs without fixing underlying problems of structural inefficiency.

China could instead discourage household savings and encourage consumption. China has one of the world’s highest national savings rates, more than triple the average for emerging economies (IMF, December 11, 2018). Chinese domestic consumption is increasing as discretionary income grows, but meaningfully curbing household savings would require shifts in demographics, the social safety net, and credit access. Some of these levers might be outside Beijing’s control or ability to tightly manage. Beijing’s new economic plans are accordingly directed towards the world beyond China’s borders.

The Belt and Road Initiative

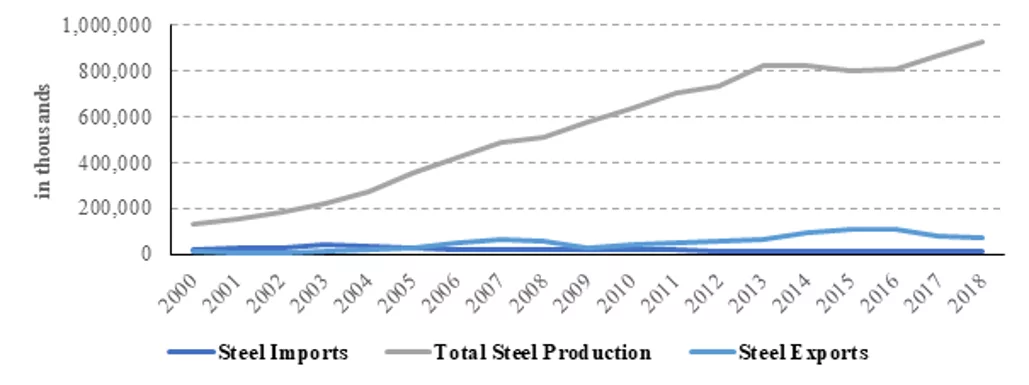

The Belt and Road Initiative is Chairman Xi’s signature foreign policy initiative. The BRI aims to translate China’s economic potential into a global network of alliances. Beijing touts the initiative as an opportunity for “win-win cooperation” between itself and participating countries, but the BRI primarily serves China’s own domestic economic concerns—most particularly, the industrial overcapacity problem. In one prominent example, Chinese steel production skyrocketed at the turn of the century alongside China’s steep economic growth (see figure 2).

The growth of state-led steel and coal firms facilitated the quick construction of China’s roads, ports, bridges, dams, and power plants. Chinese steel demand, buoyed by the real estate sector, continued to grow through 2019—however, domestic supply has still outpaced demand, and early projections expect a drop in domestic demand in 2020. [2]

Past industrial policies left Chinese officials with a stark choice between boosting Chinese construction abroad or shutting down domestic coal and steel plants—which in turn would cause political and social unrest. BRI provides an opportunity for the former by allowing Chinese state-led firms to maintain high production levels amid slowing Chinese economic growth. While Beijing’s “Going Out” policy has encouraged Chinese firms to invest overseas for many years, BRI is a far more ambitious iteration. BRI projects entail region-spanning road, rail, and power infrastructure that employ China’s domestic resources—as well as reorienting global political and economic relations with China at the center.

Figure 2. Chinese Steel Production and Trade (2000-2018)

However, BRI could prove a double-edged sword, as it does little to improve Chinese capital efficiency. BRI pumps capital into China’s inefficient firms that do not naturally serve any market at home or abroad. Further, Beijing has loaned billions to countries with questionable ability to repay their debts. [3] BRI ironically had more tenable prospects when it was first formulated amid higher Chinese economic growth in 2013. Slower economic growth means that Beijing cannot afford for BRI countries to regularly default as the cost of state firms remaining engaged.

BRI outwardly seems like an effort to displace U.S. global influence and acquire dual-use infrastructure through predatory loans, but that notion ignores the initiative’s trajectory and U.S. fault in failing to provide alternative investments that fill global infrastructure gaps. Instead, BRI more likely will fuel tensions with the United States by increasing global instability. The initiative facilitates kleptocracy and raises the likelihood of global debt distress (Foreign Policy, January 15, 2019). For the most part, Beijing does not intentionally engage in debt-trap diplomacy, but BRI lending is massive in scale and lacks institutional mechanisms that consider borrowers’ debt sustainability. Beijing may not be able to continue writing off and deferring debt payments as Chinese growth slows (China Brief, September 26, 2019). The United States would oppose BRI on these grounds alone if global debt distress increases.

Global Value Chain Advancement

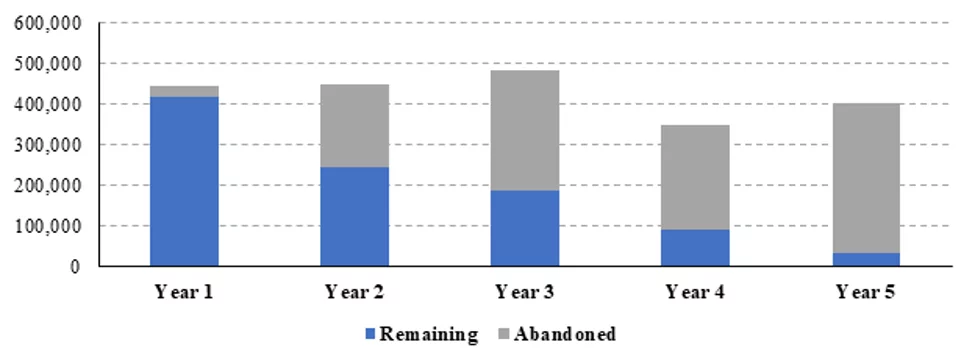

BRI may not address capital efficiency problems, but Beijing has other plans that do, including “Made in China 2025” and its recent Five-Year Plans (FYP). Indigenous innovation is at the heart of all these initiatives. Beijing clings to authoritarian capitalism, in which the Chinese government owns many large firms and determines which sectors receive subsidies and market protection, because the system affords tight social and political control and allows Beijing to redirect capital toward geostrategic aims. This commitment to industrial policy precludes China from bolstering capital efficiency through free markets. Beijing instead intends to enhance China’s innovative capacity at the state level. China has led the United States in patent applications for nearly a decade, but most Chinese patents hold little value—and many are discarded within five years, because they are not worth the fees to keep them (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Chinese Design Patents by Status

Beijing accordingly created plans promoting indigenous innovation, which are intended to increase China’s capital efficiency through state-led capitalism. First, Beijing developed “Made in China 2025” as a ten-year strategic plan in 2015 that would transform China into a leading high-value economy. Made in China 2025 identifies ten high-tech industries that the State Council deems critical to advanced economic competitiveness. Even though Beijing has quietly phased out public references to Made in China 2025 amid the trade war, some U.S. observers have criticized recent policies as a rehash of the original plan (SCMP, November 20, 2019). The State Council’s 13th FYP similarly elevated indigenous innovation as its central pillar, calling for China to improve its global innovation ranking, increase research and development (R&D) personnel and spending, and boost patent filings (PRC National Development and Reform Commission, March 15, 2016). The State Council has similarly signaled that industrial competitiveness through innovation will feature heavily in the upcoming 14th FYP, to cover the years 2021-2025 (PRC State Council, November 26, 2019).

To be sure, China is boosting domestic innovation capacity by improving its research institutions, but Beijing fosters “indigenous” innovation through illicit foreign policy tools—including intellectual property (IP) theft, forced technology transfers, and opaque foreign investments that siphon innovation from advanced economies (DIUx, January 2018). First, Chinese IP theft costs the United States alone as much as $600 billion annually (IP Commission, February 2017). Second, Beijing consistently compels foreign firms to enter joint ventures or store their data on Chinese servers in order to access the Chinese market (PRC State Council, 2015 [National Security Law]; 2016 [Cybersecurity Law]). For example, 20 percent of member firms in the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai report they have been pressured to transfer technologies, with higher rates among firms in industries the State Council considers strategically important (American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, July 2018).

Third, Beijing has taken advantage of advanced economies’ weak investment screening processes to gain access to critical technologies. In 2016, Midea, one of China’s largest commercial-appliance manufacturers, took over Kuka, Germany’s largest industrial robotics firm—an unusual move given that Midea primarily sells air conditioners and washing machines. These illicit policies work toward improving Chinese capital efficiency but undermine U.S. economic competitiveness and have driven some White House officials toward a harder stance on trade with China. [4] The United States is unlikely to allow China to continue these practices unchallenged.

This article will be continued in the next issue of China Brief.

Sagatom Saha is an independent energy policy analyst based in Washington, D.C. His writing has appeared in Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, Defense One, Fortune, Scientific American, and other publications. He is on Twitter @sagatomsaha.

Notes

[1] Many examples of this could be cited, but for one of the most recent and prominent examples, see the open letter signed in July 2019 by 100 prominent persons in the fields of government, academia, and business at: M. Taylor Fravel et al., “China is Not an Enemy,” The Washington Post (July 3, 2019). https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/making-china-a-us-enemy-is-counterproductive/2019/07/02/647d49d0-9bfa-11e9-b27f-ed2942f73d70_story.html.

[2] “China to support global steel demand growth this year,” Argus Media, October 14, 2019, https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news/1994982-china-to-support-global-steel-demand-growth-this-year; “China’s steel industry burdened by overcapacity, workers balk at shutting plants,” South China Morning Post, n.d., https://www.scmp.com/business/commodities/article/1570891/chinas-steel-industry-burdened-overcapacity-workers-baulk; “China’s steel output expected to drop in 2020 after infrastructure, real estate boom led to record 2019,” South China Morning Post, December 12, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3041746/chinas-steel-output-expected-drop-2020-after-infrastructure.

[3] John Hurley et al., “Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective,” Center for Global Development, March 4, 2018, https://www.cgdev.org/article/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-heightens-debt-risks-eight-countries-points-need-better; Corina Pons, “Venezuela faces heavy bill as grace period lapses on China loans,” Reuters, April 27, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-china/exclusive-venezuela-faces-heavy-bill-as-grace-period-lapses-on-china-loans-sources-idUSKBN1HY2K0; Jeremy Page and Saeed Shah, “China’s Global Building Spree Runs Into Trouble in Pakistan,” Wall Street Journal, July 22, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-global-building-spree-runs-into-trouble-in-pakistan-1532280460.

[4] For further detail and discussion of this issue, see: Amie Tsang, “Midea of China Moves a Step Closer to Takeover of Kuka of Germany,” The New York Times, July 4, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/05/business/dealbook/germany-china-midea-kuka-technology-robotics.html?module=inline; and Yu Zhao, “U.S. trade negotiators want to end China’s forced tech transfers. That could backfire.,” The Washington Post, January 28, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2019/01/28/u-s-trade-negotiators-want-to-end-chinas-forced-tech-transfers-that-could-backfire/.