The Ukrainian Coal Mining Industry: Problem Child or Savior?

Publication: Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 167

By:

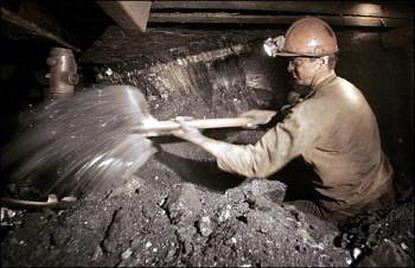

Coal mining, and especially coking coal, has been a very problematic industry in Ukraine -it is highly inefficient due to outdated machinery and the depth of its mines. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), "The average mine depth is more than 700 meters; in approximately 20 percent of mines it is 1,000-1,400 meters." It is dangerous for miners and has depended for years on large state subsidies. Despite the dangerous working conditions (Ukraine has the world’s second largest fatality rate in coal mining accidents after China) and outmoded production methods, coal is the only domestically available alternative fuel Ukraine has to keep its demand for Russian gas from mushrooming out of control.

Latest figures show that coal accounts for 40 percent of fuels used in Ukrainian power plants, 10 percent in district heating plants and 45 percent in industry. Estimates of Ukrainian coal reserves vary. The World Energy Council estimates total coal reserves in Ukraine at 52 billion tons, the 8th largest in the world. The U.S. Energy Information Administration claims that:

"Ukraine has 37.6 billion short tons in proven coal reserves, 17.9 billion short tons of which is anthracite and bituminous coal, and 19.7 billion short tons of which is lignite and sub-bituminous, accounting for about 15 percent of the former Soviet Union’s total reserves. Production and consumption of coal in Ukraine have been relatively flat since 1996, after a precipitous fall off in production after gaining independence. In 2004, the country produced 69.3 million short tons of hard and brown coal, while consuming roughly 77.5 million short tons, making Ukraine a net coal importer, despite its sizeable resources" (www.eia.doe.gov).

The Ukrainian coal mining industry has also been a controversial political issue for the country’s leadership. Located in the heavily industrialized and populous Eastern region of the Donbas, where the Party of Regions has its main support base, Western-oriented politicians, try as they may, have been unable to establish any significant following in this critical region. In September, the Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko decided to strengthen her hand in the coal industry by seeking to begin in 2010 a large scale effort aimed at the modernization and reconstruction of the country’s coal mines.

In 2008 and 2009 Tymoshenko increased wages and pensions for coal miners and is now looking to get to the core of the industry’s problem. Tymoshenko announced on September 10 that she intended to pay for the technical modernization of the mines from the state budget for 2010 and from the government’s stabilization fund. 1 billion hryvnia ($110 million) will be earmarked for construction costs and 250 million hryvnia ($27.7 million) for renovation (UNIAN, September 10). This, according to the prime minister, will increase coal production in 2010 by 1.5 million metric tons which would gradually rise to 7.8 million tons.

How realistic are Tymoshenko’s plans and projections? With the drastic fall of the Ukrainian hryvnia in 2009 (from 4 hryvnia to the dollar in 2007, reaching 9 to the dollar this year), the investment figures cited by Tymoshenko seem to be too little, too late.

This was not the first time that Tymoshenko has attempted to reform the coal industry. She tried to reform the industry while she was deputy prime minister from 1999 to 2001. She was abruptly removed from office in January 2001 by former President Leonid Kuchma, charged with fraud and money laundering, and jailed for several weeks. The charges against her were eventually dismissed. The coal industry’s losses have been growing rapidly and when the Ukrainian steel making industry collapsed earlier this year, the coal industry saw catastrophic losses. The coking coal industry is a case in point.

For the past decade, successive Ukrainian governments have provided massive subsidies to the coking-coal industry. This policy has been, in fact, a subsidy to the metallurgical industry by providing it with low-cost coke. These subsidies, in turn, led to accusations of Ukrainian manufacturers dumping steel onto world markets. On her website, U.S. Senator Debbie Stabenow stated that, "from 1997 through 2000, carbon steel slab imports [into the United States] from key producers have risen dramatically: Brazil up 25 percent; Mexico 13 percent; Russia 106 percent, and Ukraine 542 percent."

However, the troubles in Ukraine’s coal industry far surpass those of its other energy sectors:

1. Restructuring the coal industry would mean the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs in a politically sensitive region.

2. Retraining programs for coal miners are not in place; the prospects for miners performing other jobs are bleak.

3. Entire municipalities in the Donbas Basin rely on the coal industry to pay for medical care, schools, public transportation, and other vital infrastructure.

How the Ukrainian government intends to handle this problem is difficult to forecast. Any coal reforms are sure to provoke angry reactions from vested interests in the Donbas Basin and from members of parliament involved in the metallurgical and energy-generation sectors of the economy. The Donbas has shown itself willing to raise the specter of territorial separatism in order to maintain existing coal subsidy policies and schemes. The country’s eastern regions had also threatened to secede as a possible response to the Orange Revolution demonstrations in Kyiv. The reality of the threat of separatism remains questionable, but few have any doubts that the owners and managers of the coking coal-coke-metallurgical industries in Ukraine will lobby to prevent the implementation of far-reaching reforms and will continue to use coal as a political weapon.