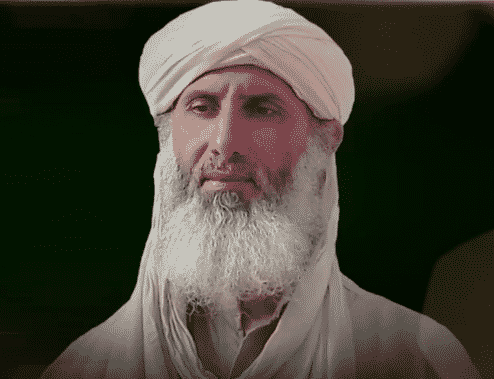

What’s Behind Taliban Leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar’s Heightened Diplomatic Visits?

What’s Behind Taliban Leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar’s Heightened Diplomatic Visits?

On February 16, the Taliban’s deputy leader and chief of its Qatar political office, Mullah Abdul Ghani, better known as Mullah Baradar (meaning brother), issued an “open letter” to the American public calling on “the American side to remain committed to the full implementation” of the Doha Agreement, which the United States and the Taliban signed on February 29, 2020. Striking a non-aggressive tone in the letter, Baradar said that “the Afghan issue cannot be resolved through the use of force” and stressed that the Taliban is “sincerely committed to finding a political solution to the ongoing conflict” (Voice of Jihad, February 16).

Baradar’s letter came amid reports that the U.S. is considering a review of the Doha Agreement, under which it committed to a full troop withdrawal by May 2021. It appears now that American troops will remain in Afghanistan beyond the 18-month deadline the U.S. agreed to (Tolo News, February 19). The Taliban has warned that if American troops do not leave it will use its “legal right to free its homeland” through “every lawful means necessary” (Arab News, February 2).

Since December, the Taliban has stepped up its global diplomatic outreach, and Baradar and Sher Mohammed Abbas Stanikzai, deputy head of the Taliban’s Qatar political office, have led Taliban delegations to Pakistan, Iran, Turkmenistan and Russia (Gulf Today, February 3). According to an Afghan government official, Baradar had been “sidelined” by the appointment last August of hardline cleric Abdul Hakim Ishaqzai as the Taliban’s top negotiator in the intra-Afghan talks. However, as of December, Baradar is “back in the spotlight.” [1] So who is Baradar, and why is he important to the Taliban’s recent diplomatic drive?

Role in the Taliban Regime

A Durrani Pashtun of the Popalzai tribe, Baradar was born in 1968 in the village of Yatimak in Afghanistan’s Uruzgan province. He spent his early years in a madrassa in Kandahar. He joined the mujahideen to fight the Soviets in the 1980s and was active in the Kandahar province’s Panjwayi area. Baradar’s close relationship with Mullah Mohammad Omar, the Taliban’s founder-chief, can be traced back to the 1980s. The two were part of the same mujahideen group and reportedly related by marriage through two sisters. In 1994, they co-founded the Taliban (Afghan Bios, June 25, 2020).

In addition to playing an important role in the military operations that culminated in the Taliban’s capture of Kabul in 1996, Baradar also held key posts in the Taliban regime (1996-2001). He was a corps commander for western Afghanistan and later was garrison commander of Kabul (Dawn, February 17, 2010). He also served as Deputy Minister of Defense. Baradar was reportedly “responsible for a number of massacres in 1998-2000.” During the Taliban’s military offensives in the Shamali region north of Kabul in 1999, he is said to have personally ordered and overseen summary executions. [2] His role in the Taliban regime led to his inclusion on the United Nations Security Council Sanctions List (United Nations Security Council, February 23, 2001).

Mullah Omar’s Deputy

Baradar was among several top Taliban leaders who reportedly offered to surrender following the ouster of the Taliban regime toward the end of 2001. In return for “immunity from arrest,” these leaders apparently agreed to “abstain from political life” and accept the leadership of Hamid Karzai. But their surrender offer was not accepted (Afghanistan Analysts Network, October 28, 2018). Soon afterward, Baradar and other Taliban leaders fled to Pakistan, from where they have waged the almost two-decades-long insurgency. Considered “more cunning and dangerous” than Omar, Baradar is said to have played an important role in reviving the Taliban and reorganizing it to fight a guerrilla war against the U.S.-led coalition forces (Dawn, February 17, 2010).

Baradar rose steadily in the Taliban hierarchy in the 2000s. In 2003, he was appointed second deputy to Omar and thus stood third within the Taliban hierarchy, after Omar and Mullah Obaidullah. Following Obaidullah’s arrest in 2007, Baradar took over the number two position within the Taliban (Afghanistan Analysts Network, October 28, 2018). Omar’s failing health saw Baradar take charge of the organization. In addition to running the group’s military affairs and the Rahbari Shura (leadership council), Baradar was managing its financial affairs and appointing and dismissing commanders (Dawn, February 17, 2010).

‘Best Hope for Peace’

Then, in February 2010, Pakistani authorities arrested Baradar in Karachi. Baradar was reportedly engaging in secret talks directly with the then-government of Hamid Karzai. Pakistani authorities were apprehensive that such talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban would result in a deal that could leave Islamabad with less clout in Kabul, and apparently decided to pre-empt this by taking Baradar into custody (Indian Express, August 23, 2010).

All the main actors in the Afghan conflict perceive Baradar’s potential value to peace talks. In Kabul, he is “seen as a moderate, someone who is interested in a political settlement. If during the Karzai years he was seen as capable of bringing moderate Taliban leaders on board a negotiated settlement, he is now seen as Afghanistan’s best hope for peace.” [3] According to U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad, both Karzai and President Ashraf Ghani saw Baradar’s potential to “play a pivotal role in the peace process” (The Hindu, February 9, 2019). They repeatedly pressed the Pakistanis for his release. [4] According to terrorism analyst Abdul Basit, Baradar’s significance to Pakistani authorities can be gauged from the fact that they did not release him for eight years despite strong requests by the Afghan and American governments, and the Taliban, for his release. [5]

Pakistan regarded Baradar as its “winning pawn in the unfolding Great Game in Afghanistan” (Indian Express, March 23, 2019). It saw him as “a valuable card to be played at an appropriate time and was unwilling to surrender this card” by releasing him early in the game. As for the Americans, they have long viewed Baradar as a “moderate and a useful facilitator in peace talks.” [6] Consequently, when the administration of President Donald Trump became interested in negotiating an agreement with the Taliban that would pave the way for American troop withdrawal, Khalilzad urged Pakistan to release him, a request that Islamabad agreed to (The Hindu, February 9, 2019).

Following his release from Pakistani custody in October 2018, Baradar engaged in talks with the Khalilzad-led U.S. delegation. The negotiations resulted in the Doha Agreement, which Baradar signed on behalf of the Taliban. His role in negotiating this agreement, which is widely looked on by the Taliban as a U.S. “surrender document,” boosted his stature in the Taliban. [7]

At the Forefront Again

Yet, within a few months of this achievement, Ishaqzai replaced Baradar as the Taliban’s chief negotiator in the talks with the Afghan government. Appointing Ishaqzai, who is experienced in Islamic jurisprudence, as the top negotiator to the intra-Afghan talks was aimed at assuring conservatives in the ranks that the Taliban leadership remains committed to Islamic values and sharia law (see Militant Leadership Monitor, December 4, 2020). Keeping Baradar at the helm of the Taliban team at the intra-Afghan talks would not have served that purpose. However, with these talks having been in a state of suspension since January and the Taliban seeking to influence world opinion in the context of the uncertainty over the Doha Agreement’s future, Baradar is once again at the forefront of the group’s diplomacy.

The flurry of Taliban visits abroad in recent months is in “retaliation” for Washington’s review of the Doha agreement. The Taliban is mobilizing the support of major powers and Afghanistan’s neighbors for its position that the United States must pull its troops out of the country. [8] To draw the support of these countries, Baradar has been projecting the Taliban as a responsible actor that will contribute to regional security and stability. In Ashgabat, for instance, Baradar expressed the Taliban’s support for multilateral gas pipeline projects, rail corridors and power lines (The Express Tribune, February 18). Baradar’s diplomatic blitz has also been aimed at bolstering the Taliban’s legitimacy in the Afghan political landscape. [9] His image as a “moderate” leader helps the Taliban achieve these objectives.

Role in “Future Set-up”

There is speculation in social media that Baradar is being considered for an “important position in a future set-up” in Afghanistan. His recent diplomatic blitzkrieg could be aimed at boosting his profile and stature. As one of the Taliban “old guard” and a co-founder of the group, he commands respect in the Taliban. Unlike other Taliban leaders, many of whom are seen as “mass murderers,” Baradar “comes across as a moderate” and “will find more acceptability among ordinary Afghans.” He also seems “acceptable to the U.S. and Pakistan”; they see him as “someone they can work with.” However, Baradar has not been active on the battlefield for decades and is not in touch with the new generation of Taliban fighters, who question his military credentials. [10]

Questions abound relating to his eight years in Pakistani custody. How did it impact him? This reportedly has “fueled suspicions over his loyalties.” [11]

Importantly, will Baradar be acceptable to the Taliban conservatives and hardliners? Given the deep divisions within the Taliban, Baradar could find the strongest opposition to his taking on a future leadership role in the organization coming from his hardline colleagues.

Notes

[1] Author’s Interview, Kabul-based Afghan government official, February 18. [2] The Afghanistan Justice Report, “Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: 1978-2001,” accessed on February 22, https://afghanistanjusticeproject.org/warcrimesandcrimesagainsthumanity19782001.pdf [3] Afghan official, n. 1. [4] Ibid. [5] Author’s Interview, Abdul Basit, associate research fellow at the International Center for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR) of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, February 15. [6] Afghan official, n.1. [7] Basit, n. 5. [8] Ibid. [9] Ibid. [10] Ibid. [11] Afghan official, n.1.