Consular Pop-Ups in Canada Advance Local United Front Work

Executive Summary:

- Since 2015, the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in Canada, along with PRC consulates in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, and Calgary, have organized at least 105 gray zone activities in 22 cities across 11 provinces.

- These consular “pop-up” events threaten Canada’s national security and undermine its sovereignty, democracy, and the rules-based international order. They operate outside of designated diplomatic facilities that enjoy extraterritorial protections and likely without the consent of the Canadian government.

- The events are framed as providing consular services to the diaspora community in Canada, but they also provide opportunities for political work, including influence operations, surveillance and coercion, and overseas political mobilization.

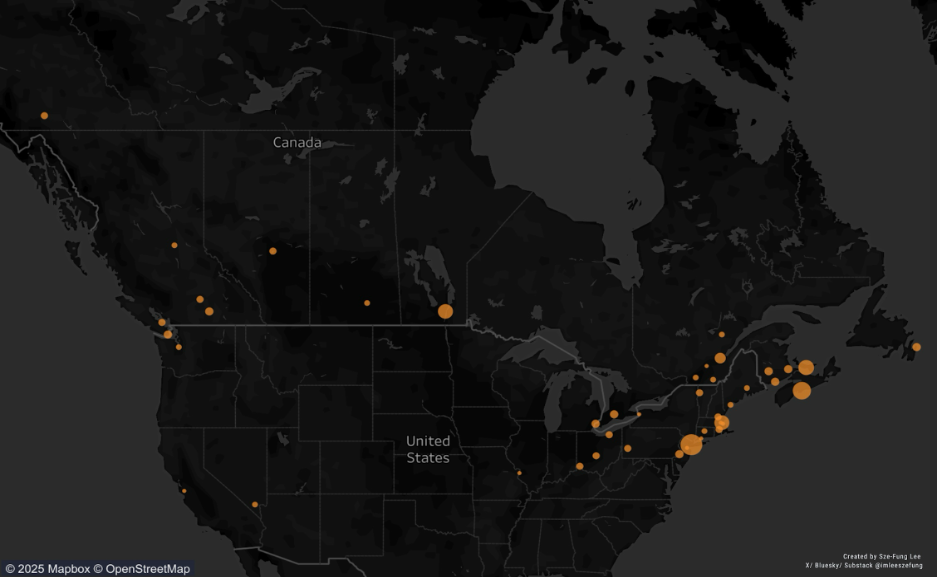

- The PRC’s strategy in Canada differs from that used in the United States. In Canada, all consulates and the embassy are involved, events are more evenly distributed across the country, and they specifically target provincial capitals rather than major cities. Consulates also co-host with a smaller set of community organizations, and tend to hold events in private, rather than public, spaces.

Over the past decade, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has organized and hosted consular pop-ups across the United States at non-diplomatic facilities, such as Chinese restaurants and supermarkets (China Brief, October 21, 2024). These events are likely part of a global operation under the political initiative of “bringing consular services into the community/grassroots” (领事服务进社区/基层). PRC consulates have conducted similar activities in Canada, the United Kingdom, Japan, Hungary, Tanzania, Jamaica, and beyond. Consular services provided by local offices currently appear limited in scope, by vary by country. Deeper investigation of activities in Canada indicate that it is an outlier, with consular officials hosting an extensive array of activities over the last decade.

As of November 2025, PRC diplomats had held over 100 pop-up events across 11 provinces and 22 cities in Canada since 2015. These events can be seen as “gray zone” activities, as they exploit an ambiguity in international law. It is unclear whether pop-up–style consular service events in non-designated diplomatic facilities are legal. Given that these events also serve as a mechanism for political activities and influence operations through community outreach, they may constitute violations of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (International Law Commission, 2005). [1] Even if they were to be found to operate within the letter of the law, however, legality does not equal diplomatic norm compliance. The PRC’s extensive organization of pop-ups across the world remains an unusual practice. It not only exacerbates Beijing’s preexisting extraterritorial law enforcement efforts but also creates new norms that fundamentally challenge the international rules-based order.

This scale of operations is much larger than in the United States. All PRC consulates and the PRC Embassy in Canada are involved, targeting most provincial capitals. This likely reflects a sub-national strategy aimed at maximizing influence at the provincial level. Their increased intensity in recent years may also be a response to high-profile cases of PRC influence in Canada in recent years that limit the utility of a national-level strategy.

Consular Pop-Ups as Gray Zone Activities Across Canada

Starting in 2015, the PRC Embassy in Canada, along with PRC consulates in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, and Calgary, have organized at least 105 gray zone activities. The venues for these events range from hotel conference rooms and Chinese cultural centers to university classrooms and clubhouses. Such pop-up events have been organized under the initiative of “bringing consular services into the community,” as a manifestation of “people-centered diplomacy” (外交为民) (WeChat/PRC Consulate in Toronto, October 24, 2018).

These events have taken place in 22 cities across 11 provinces: Edmonton in Alberta; Kamloops, Kelowna, Nanaimo, Prince George, and Victoria in British Columbia; Winnipeg in Manitoba; Fredericton, Moncton, and Saint John in New Brunswick; St. John’s in Newfoundland and Labrador; Halifax in Nova Scotia; London and Windsor in Ontario; Charlottetown in Prince Edward Island; Montréal, Québec City, Saguenay, Sherbrooke, and Trois-Rivières in Québec; Regina in Saskatchewan; and Whitehorse in Yukon. The most recent activity took place in London, Ontario, on November 1. It was organized by the PRC Consulate in Toronto (author research, November 2025).

The events likely violate international law. This is because they provide consular services but operate outside of designated diplomatic facilities that enjoy extraterritorial protection. It is also unlikely that the Canadian government has consented to such activities. Even if consent were obtained, evidence suggests that these events go beyond consular services by also providing a platform for political activities. This includes influence operations and cognitive warfare targeting Chinese diaspora communities, united front work strengthening the PRC’s capacity for overseas political mobilization, and the creation of new norms that exacerbate Beijing’s preexisting extraterritorial law enforcement efforts.

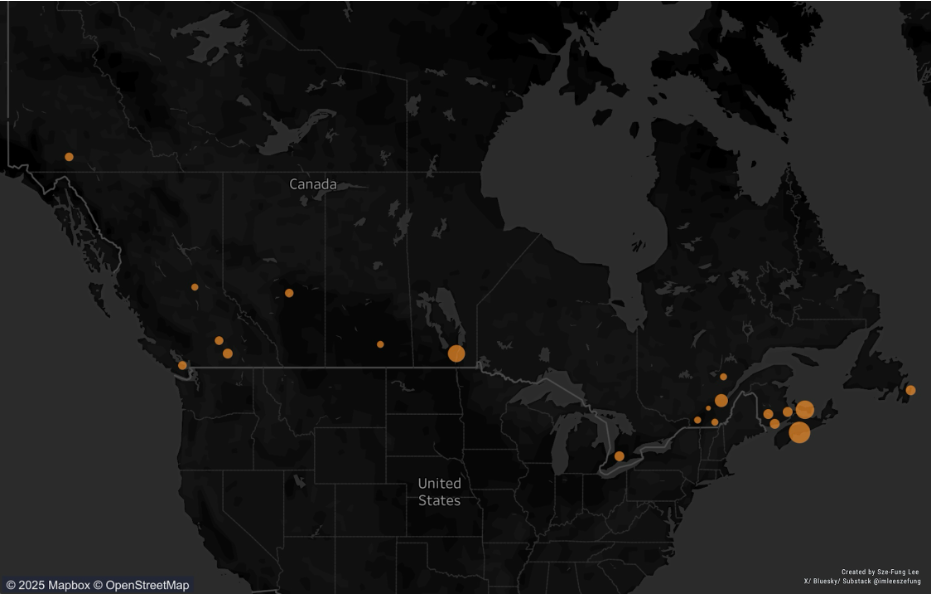

Figure 1: Distribution Map of Pop-up Events in Canada, 2015–2025

(Source: Author’s research)

In 2022, for instance, Deputy Consul General Hong Hong (洪红) led a team from the Toronto Consulate to host two on-site document processing sessions in Manitoba. Hong described the events as an effort to align with directives from the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to explore approaches to enhance the well-being of and strengthen ties with overseas Chinese communities (Consulate-General of the PRC in Toronto, December 8, 2022). Representatives from the Toronto Consulate hosted events in a Chinese Cultural Center on November 26 and, on November 27, far outside Toronto at the University of Manitoba with the help of the Winnipeg Chinese Cultural and Community Center (温城中华文化中心), Fenghua Voice (枫华之家), and the University of Manitoba Chinese Students and Scholars Association (曼尼托巴大学中国学生学者联谊会) (WeChat/PRC Consulate in Toronto, November 18, 2022).

A WeChat article published by the Toronto Consulate also claims that the consular team made a “special trip” (专程) to an elderly couple’s residence in Manitoba to process their passport renewal application when they were unable to attend an event (PRC Consulate in Toronto, December 8, 2022). Home visits (上门办证) like this are an unusual diplomatic practice. They are questionable on legal grounds, but more importantly they carry significant security implications. This is because they may function as tools for surveillance or coercion under the guise of “consular services,” and could be used to impose direct or indirect pressure on individuals Beijing deems to be political threats.

This sets a potentially alarming precedent for the PRC’s growing and pervasive efforts to extend its outreach and exert control over diaspora communities. In the name of providing consular services, PRC officials are knocking on doors on Canadian soil—likely with diplomatic immunity. While consent is required to justify these activities, it likely can be fabricated by consular officials. These gray-zone activities, therefore, pose a significant threat concealed within Beijing’s broader coercive repatriation campaigns and transnational repression. They create new norms that exacerbate Beijing’s extraterritorial law enforcement efforts and challenge the international rules-based order.

Figure 2: Pop-up Consular Service Events in Winnipeg, November 26–27, 2022

(Source: PRC Consulate in Toronto, December 8, 2022)

Sub-National Focus Across Canada, Unlike in the United States

All PRC consulates in Canada, as well as the PRC embassy, are involved in the pop-up events. The embassy in Ottawa appears to play a significant role. It has organized 35 activities over the past decade, making it the organizer of the largest number of events in Canada. Pop-ups hosted by other consulates are more evenly distributed, with each having managed 19–26 events. This contrasts with the situation in the United States, in which only some consulates are involved in such activities. The large scale and balanced distribution of events in Canada suggests that a more coordinated and centralized country-wide strategy might lie behind them, rather than a localized or fragmented approach.

Events in Canada are all held in more controlled settings than in the United States. Instead of being hosted in public spaces, Canadian consular events take place in semi-private settings where participation generally requires advance registration. [2] Starting around March 2024, for instance, the PRC Consulate in Vancouver began to withhold venue locations until registration (PRC Consulate in Vancouver, March 16, 2024). This comparatively careful and controlled operational approach suggests that consulates have sought to keep these gray zone activities under the radar.

A much more limited set of co-hosting organizations have been involved in pop-up events in Canada than in the United States. Data indicate that events often use the same venues repeatedly, suggesting a smaller network of local partners. This, however, is likely influenced by geography, as a majority of events in Canada have been held in small and mid-size cities and provincial capitals like Edmonton, Kamloops, Prince George, Winnipeg, and Halifax, where Chinese diaspora communities are smaller and local entities are fewer. Beyond operational differences, the decision by consular officials to host events in these cities may also reflect a strategic agenda that differs from the one followed in the United States.

Compared with U.S. operations, events in Canada target provincial capitals and smaller regional centers rather than major metropolitan areas. This suggests that influence operations for ideological warfare and united front network building remain a central objective, but at a sub-national level. As shown in Figure 1 above, the highest number of gray zone activities have taken place in Halifax (19), Charlottetown (14), and Winnipeg (12). Notably, 10 out of Canada’s 14 provincial and territorial capitals have been targeted, indicating a strategic focus on administrative and regional hubs. [3] The exceptions are Ottawa, Toronto, Iqaluit, and Yellowknife, which are likely excluded as they do not align with the sub-national united front strategy. Ottawa, the national capital, and Toronto, Canada’s largest city, are large metropolitan centers; while Iqaluit and Yellowknife are likely too remote to make influence operations viable or worthwhile.

Targeting administrative and regional hubs aligns with the traditional united front strategy of “leveraging local power to encircle the central authority” (以地方包围中央) or “encircling the cities from the countryside” (农村包围城市). This strategy was developed by Mao in the late 1920s. At the time, Mao argued that because the CCP was weaker than its adversary it should first focus on building power and influence in rural areas before expanding outward through guerrilla tactics (News of the Communist Party of China, accessed December 1). In essence, sub-national united front work aims to co-opt, influence, and manipulate individuals and groups at the local level to gradually isolate and pressure central authorities to align with the Party’s political agenda. By influencing multiple provincial capitals simultaneously and coordinating operations in other cities within the same provinces, Beijing could maximize its influence on provincial policymaking and gain sufficient leverage to push back against unfavorable federal policies at the provincial level while shaping policy at the national level.

Figure 3: Distribution Map of Pop-up Events in Canada and the United States, 2015–2025

(Source: Author’s research)

PRC influence operations, and especially united front work, have faced significant pushback at the national level in Canada. The detention of Canadian citizens Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor in the PRC, revelations about overseas PRC police stations and electoral interference, and a public inquiry into foreign interference, likely have led the PRC to shift its tactics. Beijing’s focus on provincial capitals could exploit gaps and advance its united front work in relatively untapped areas. From the PRC’s perspective, sub-national efforts can influence decision-making at the local and provincial level while minimizing attention at the national level. This may also explain attempts to operate in controlled, rather than public, settings. Another possible reason for avoiding larger cities like Toronto is that they already have large Chinese diaspora presences and well-developed united front networks that the Party can mobilize for kinetic events, such as counterprotests.

The Party’s wider objectives for gray-zone consular activities are currently unclear, beyond strengthening united front networks. But by expanding capabilities to influence provincial capitals, Beijing could target a wide range of political and strategic sectors, including Canada’s critical minerals, which exist in virtually every province.

Conclusion

PRC consular gray zone activities should be viewed as part of a broader hybrid warfare strategy rather than isolated incidents. Potential ramifications, such as political mobilization, should not be underestimated. Evidence indicates that these events continue to operate and remain largely unchecked in Canada, the United States, and beyond, despite published research and media coverage drawing attention to the issue (PRC Consulate in New York, August 8).

The wider context of this deepening gray zone strategy in Ottawa’s re-engagement with the PRC under Prime Minister Mark Carney (Prime Minister of Canada; MFA, October 31). Currently, there is no publicly available data on whether the Canadian government is aware of PRC influence operations in the form of “pop-up” consular events that take place on Canadian soil. But these events undermine the country’s sovereignty, democracy, and the rules-based international order; and above all, they represent a threat to Canada’s national security and the security of Canadian citizens.

Notes

[1] For more details, see the author’s previous report on “pop-ups” in the United States (China Brief, June 7).

[2] Some U.S. events were also held in semi-private spaces, but they did not usually require advance registration.

[3] Targeted provincial and territorial capitals include St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador; Halifax, Nova Scotia; Fredericton, New Brunswick; Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island; Québec, Quebec; Winnipeg, Manitoba; Regina, Saskatchewan; Edmonton, Alberta; Victoria, British Columbia; and Whitehorse, Yukon.