In the Shadow of al-Baghdadi: Islamic State’s Deputy Caliph – Abu Alaa al-Afri

In the Shadow of al-Baghdadi: Islamic State’s Deputy Caliph – Abu Alaa al-Afri

Bridget Moreng

On March 18, 2015, a coalition airstrike targeted a convoy of three cars traveling in Iraq’s al-Baaj district, a remote western area near the Syrian border (Haaretz, April 21, 2015). The following day, U.S. Central Command released its daily strike update, noting that a strike near Sinjar—18 miles from al-Baaj district—“had inconclusive results” (U.S. CENTCOM, March 19, 2015). This strike, however, would turn out to be much more significant than it appeared at first glance. Among the men targeted was the most wanted man in the world: Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the brutal and evasive IS caliph.

While Baghdadi’s fate remained in question, a mysterious man waited in the wings, ready to take full control of the organization should Baghdadi succumb to his injuries. This man, known as Abu Alaa al-Afri, was IS’ new deputy caliph.

Baghdadi survived the strike but was left with a debilitating spinal injury that reportedly rendered him unable to function as the group’s day-to-day leader, a position that would be assigned to al-Afri while Baghdadi recovered (Iraqi News, April 23, 2015). Following Baghdadi’s injury, hazy details began emerging about al-Afri, though he remained an enigma through the majority of his time as IS’ No. 2. Al-Afri, whose real name is Abd al-Rahman Mustafa al-Qaduli, was born in Mosul, Iraq in 1959. Al-Afri is thought to have graduated from Mosul University’s physics department, going on to become a teacher at the al-Jazeera Secondary School in the city of Tal Afar (Azzaman, May 9, 2015). In addition to a number of jobs al-Afri occupied in Tal Afar, he had also reportedly worked as a bus driver and a preacher who was well known for stressing the importance and legitimacy of Takfiri doctrine (Azzaman, May 9, 2015). After joining IS, Al-Afri’s deeply engrained extremist views would help shape the group’s underlying ideology.

Jihadist Career

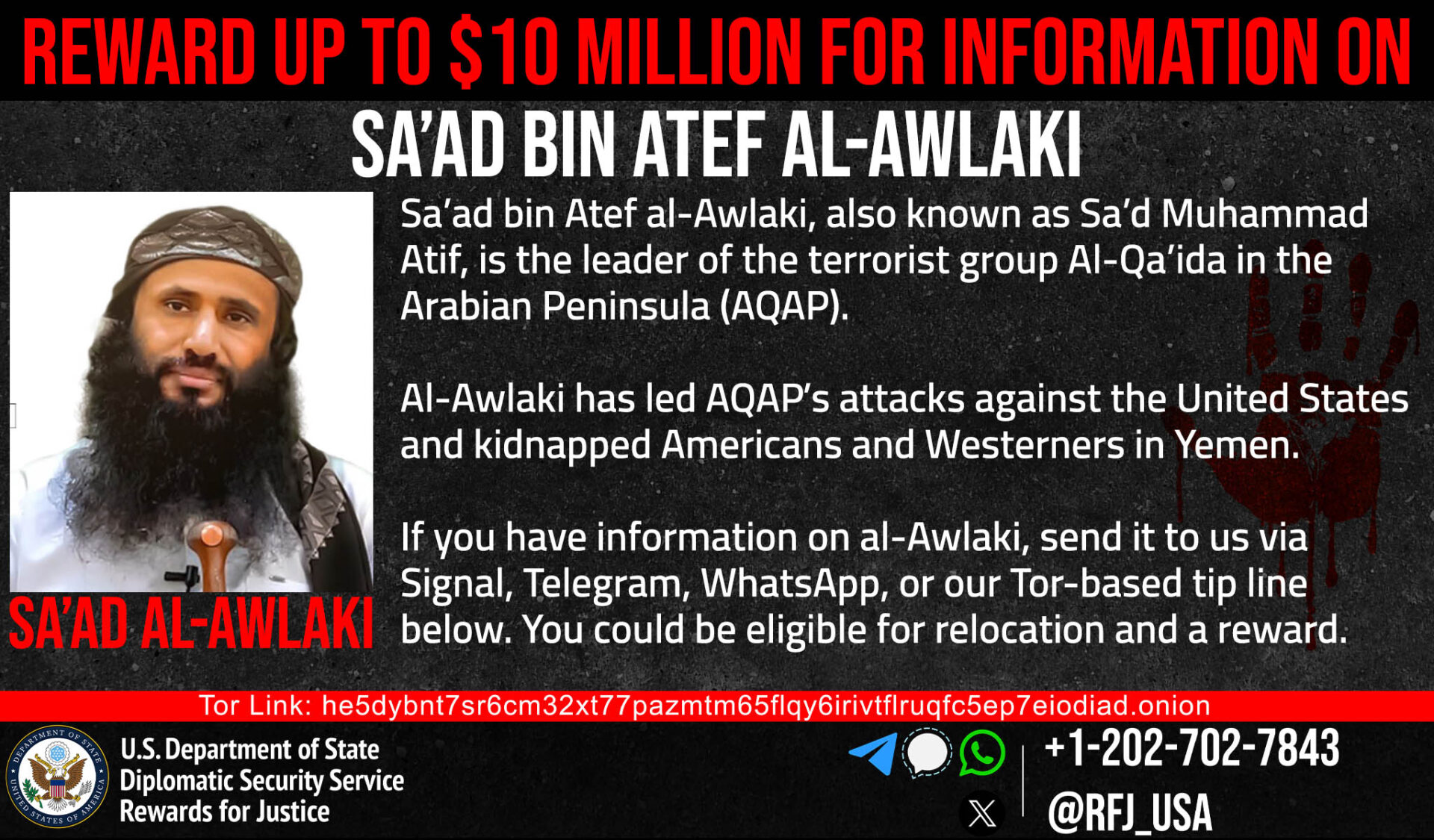

Al-Afri left Iraq for Afghanistan in 1998 after repeated arrests by Saddam Hussein’s security forces for preaching his extreme religious views. There, al-Afri came to know al-Qaeda (AQ) emir Osama bin Laden (Reuters, March 26). By the early 2000s, al-Afri had returned to Iraq, becoming active in the insurgency (Haaretz, March 25). He eventually joined al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)—IS’ predecessor organization—in 2004, under the command of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who came to see al-Afri as one of his most trusted aides (Rewards for Justice, 2015; Al-Quds al-Arabi, April 29, 2015). Al-Afri rose to prominence during his time with AQI. He worked as a liaison for the group’s operations in Pakistan and coordinated with AQ’s central leadership there, a position that requires significant trust from senior leaders (Department of Defense, March 25; The Syrian Intifada, March 25). Al-Afri also served as AQI’s emir of Mosul and oversaw Sharia authorities in northern Iraq (Rewards for Justice, 2015).

After Zarqawi died in a U.S. airstrike in 2006 (AQI changed its name to the Islamic State of Iraq, ISI, the same year), al-Afri maintained his high-ranking stature within the organization. It is even rumored that, following the death of ISI’s top leaders Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and Abu Ayyub al-Masri in 2010, bin Laden himself had advocated for al-Afri to lead the organization, though there is no hard evidence to suggest this was indeed the case (Al-Monitor, March 23, 2015). [1] After the death of Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and al-Masri, bin Laden’s chief of staff, Atiyya Abd al-Rahman wrote a letter to ISI’s Shura Council to recommend a process for selecting a new emir. In the letter, Rahman suggested that they “appoint a temporary leadership to manage affairs,” adding that it would be “best to delay…an official permanent appointment” until bin Laden was sent a short list of potential successors so that he could advise them on who to select (Pieter Van Ostaeyen, May, 3, 2015). If bin Laden did suggest al-Afri to lead the organization, his advice was not followed, as the position was filled by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in May 2010 (Al-Monitor, November 1, 2013). Baghdadi went on to rename the group ISIS in April 2013; he then changed the name to IS in June 2014 following its declaration of the caliphate.

A pro-al-Qaeda IS defector known as Abu-Ahmad claims IS puppet master Samir Abd Muhammad al-Khlifawi, also known as Haji Bakr, was behind Baghdadi’s appointment. In testimony published online in April 2014, Ahmad explained that Bakr, a former colonel in Saddam Hussein’s intelligence service who went on to became a senior leader in IS, secretly convinced the majority of ISI’s Shura council to vote for Baghdadi. He did so by taking advantage of the Shura Council members’ inability to meet as a group for fear of their safety amid widespread arrests and killings of high-ranking members within the group. As such, the members were forced to make a decision separately. Bakr supposedly corresponded with each Shura council member individually, convincing each one that the others had agreed to elect Baghdadi as the leader. Bakr convinced most of the Shura members, despite the fact that they did not know Baghdadi personally (Eldorar, April 5, 2014).[2]

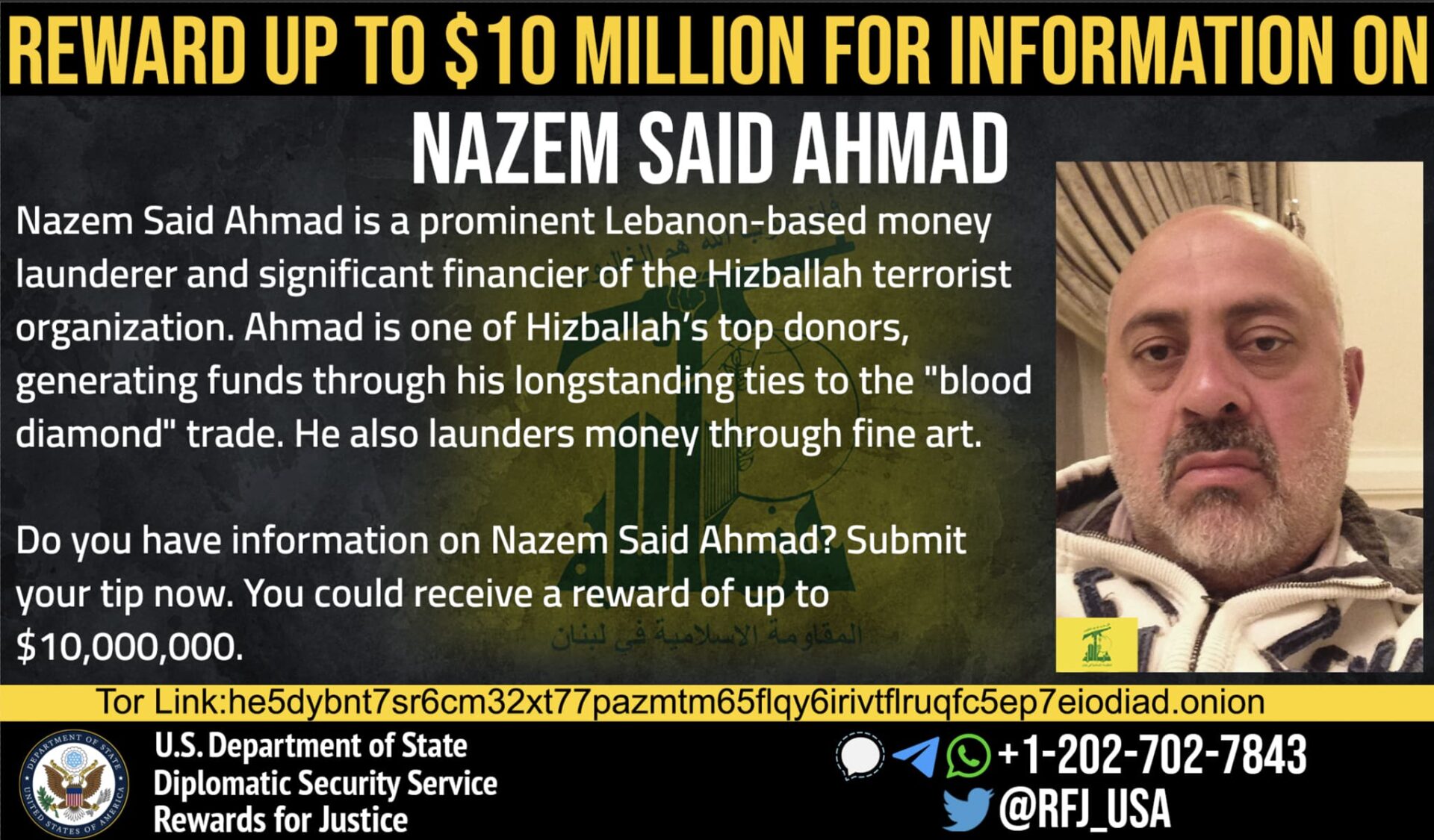

At some point, though it is unclear precisely when, al-Afri was arrested and imprisoned. While in jail, he reportedly held Sharia lectures for other detainees, many of whom were strongly influenced by his ideas and went on to join IS (Al-Quds al-Arabi, April 29, 2015). After his release from prison in 2012, al-Afri traveled to Syria, where he joined up with the ISI network (Rewards for Justice, 2015). Some have suggested that, once al-Afri joined ISI, he played a significant role in the setting the ideological framework for the group, influencing the group’s excessive brutality (The Syrian Intifada, March 25). Al-Afri is said to have held numerous prominent positions within IS, including the general coordinator for the affairs of martyrs and women, the head of IS’ Shura council, and a liaison between Baghdadi and the emirs of various wilayas (provinces) across the group’s territorial holdings (ARA News, April 24, 2015; Al-Sumariyah, April 23, 2015). Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter additionally described al-Afri as IS’ finance minister (Department of Defense, March 25). Al-Afri is said to have been very close to Baghdadi and likely had his full trust given the importance of the positions that al-Afri held—most importantly as his deputy (Asharq al-Awsat, March 15, 2015; ARA News, April 24, 2015).

Perhaps more interesting than his positions within the organization is the internal controversy associated with his appointment as deputy caliph. Al-Afri’s promotion seemed to have caused major schisms within the organization largely due to his ethnic background as a Turkoman rather than an Arab of Qurayshi descent (the Prophet Muhammad’s tribe). Membership of the Quraysh tribe is often thought of as a prerequisite for becoming caliph, a requirement that al-Afri did not fulfill. Shortly after al-Afri was reported to have taken the role of deputy caliph, reports emerged of disagreements inside the organization, which led to significant infighting within the group. In April 2015, reports emerged that fighting had broken out between IS militants after a group of members objected al-Afri’s promotion to deputy caliph. The clashes reportedly took place in Tal Afar and resulted in the deaths of several IS fighters (Al-Sharq al-Awsat, April 29, 2015). Moreover, former Iraqi National Security Adviser Muwafaq al-Rubay’i claimed that there were “substantial internal disagreements and splits” between IS leaders after Baghdadi’s injury. Other Iraqi officials suggested that the prospect of Baghdadi’s death prompted a major internal struggle, with several senior IS leaders vying for power within the organization (Al-Ra’y, May 5, 2015).

Al-Afri’s Death

On March 25, 2016 Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter announced that al-Afri had been killed by the U.S. military (U.S. Department of Defense, March 25). IS confirmed his death in a video released by Wilāyat Nīnawā entitled “Charge of the Righteous Upon the Infidel Peshmerga #2 – Wilāyat Nīnawā” (Jihadology, May 24).

Al-Afri’s appointment as deputy caliph during a time when Baghdadi’s fate was in question allows us to see the types of schisms that may occur as a result of leadership decapitation. If Baghdadi had died and al-Afri was appointed to the emir position, it is possible that internal disagreements about al-Afri would have intensified significantly. Thus, while leadership decapitation is not a silver bullet when it comes to defeating an organization in the long-term, it may help to inflame internal power struggles within the group and weaken its overall cohesion.

Bridget Moreng is a threat analyst at the consulting firm Valens Global, where her work focuses on the Islamic State’s operations in Iraq, as well as the group’s global strategy. Follow her on Twitter at @BridgetMoreng. The author would like to thank Max Peck (@Maxwell_Peck) for contributing to the Arabic-language research for this article.

Notes

[1] In this piece, al-Afri is referred to by another alias, Haji Iman. [2] Will McCants, Director of the Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World at the Brookings Institute, discusses this situation in his book The ISIS Apocalypse, (p. 77)