Belarus’s Role in East European Energy Geopolitics

Belarus’s Role in East European Energy Geopolitics

Executive Summary

The role Belarus plays in energy geopolitics is one of the most unusual in the world. While not a petroleum supplier, it sells refined oil products to many countries. And while not a natural gas producer, it delivers the fuel to numerous countries via pipelines built during Soviet times. Its unique situation stems from Belarus’s location next to its nearly sole energy supplier, Russia, and the fact that its economy is heavily based on these hydrocarbon resources. Belarus’s dependence on below-market-price Russian energy means it has had no choice but to pursue a foreign policy that keeps it tightly within Moscow’s orbit.

Neither Belarus’s membership in the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union nor its interminable negotiations with Russia on forming a political and economic union—which Belarus wants to avoid—have prevented the two countries from succumbing to periodic oil and gas pricing disputes. Although in each successive case, they ultimately managed to resolve their disagreements, the solutions either patched over key issues or proved temporary, leading to renewed disputes down the road.

The countries are now embroiled in yet another pricing row, with Russia flexing its energy-supply muscle again to try to force Belarus into a political and economic union. As in the past, some interim solution to the dispute is likely. But if Belarus truly wants to end its dependence on Russian energy and avoid existentially deeper integration with the Russian Federation, it will need to diversify its oil and gas imports as soon as possible.

Introduction

Belarus is one of the few countries that lacks oil and natural gas but whose economy revolves around them. One important factor that helps explain this seeming contradiction is the fact that the country has several major pieces of petroleum-industry infrastructure left over from Soviet times—two refineries and networks of pipelines that deliver Russian oil and gas to Europe. The Moscow-owned pipelines that send Russian oil and gas to and through Belarus have long enabled Russia to be essentially the sole supplier of its neighbor’s energy. At the same time, the Naftan and Mozyr refineries have allowed Belarus to create value-added products like gasoline to sell to Russia and other countries. But together, these refineries’ operations now account for 19 percent of Belarus’s total export revenues.[1]

Naftan, which opened in 1958, is the oldest and largest refinery on Belarusian territory. The state-owned facility, which can convert 12 million tons of crude oil a year into other products, stands in a strategic location on the Divne River. The government has upgraded Naftan several times to improve its operating efficiency, from 70 percent in the 1970s to 95 percent today.

The Mozyr Oil Refinery, which refines eight million tons of oil a year, began operating in 1975. In 1994, it became part of a Belarusian-Russian joint venture known as Slavneft. The company retains majority ownership of Mozyr, with the Belarusian government holding 42.5 percent and employees and other individuals 14.5 percent.[2]

Both refineries receive their oil from Russia, through the Druzhba pipeline. The world’s longest oil pipeline, it runs from western Siberia to Belarus and on to Europe. The pipeline supplies Belarus with 24 million tons of oil a year, while sending another 40 million tons to Europe. Russia sends a quarter of all its oil exports to Ukraine, Belarus and Europe through the Druzhba, with a third going mainly to Poland and Germany.[3]

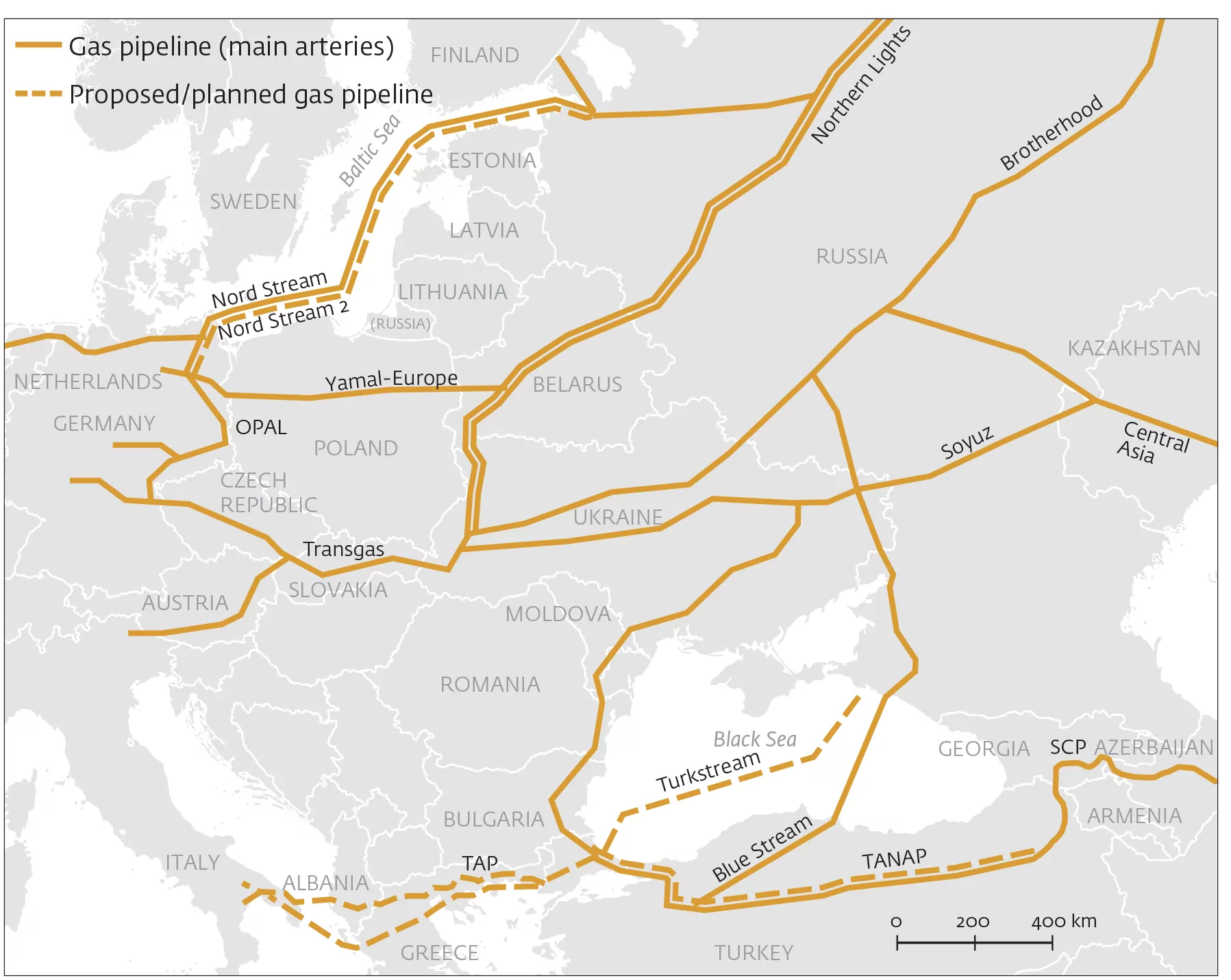

Belarus also buys around 20 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russian gas a year and annually transits 39 bcm of Russian gas to Europe. Those volumes flow mostly through the Yamal-Europe pipeline, owned by Russian state-run gas giant Gazprom.[4] Of the 39 bcm of Russian gas earmarked for European customers and transiting Belarus, 32 bcm goes to Poland, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. Belarus and Ukraine account for all the gas transported via on-land pipelines to Europe.

Gazprom additionally has a controlling interest in the Northern Lights pipeline, the Belarusian section of which is operated by the Russian gas producer’s local subsidiary, Gazprom Transgaz Belarus (formerly Beltransgaz). The Belarusian section of Northern Lights delivers 7 bcm of Russian gas to Ukraine, Poland, Lithuania, and to Russia’s European exclave of Kaliningrad. Gazprom obtained a majority stake in Beltransgaz in 2012, in exchange for discounts on the price of gas it was supplying to Belarus.[5]

The fact that the Belarusian economy is so dependent on its large eastern neighbor’s energy raw materials has created recurring spasms of tension between them since the late 1990s, just a few years after the Soviet Union disintegrated. That energy dependence is also putting pressure on Minsk to yield to Moscow’s desire for Belarus to become what amounts to a Russian fiefdom. To date, Belarus has been able to dodge some of the Kremlin’s most brazen integration demands—like putting Russian military bases on Belarusian soil. But unless Belarus can truly diversify its economy away from oil and gas, its future remains uncertain. One factor currently playing in Belarus’s favor is that its first nuclear plant, which is expected to become fully operational in 2021, will somewhat reduce its dependence on Russian oil and gas. The first reactor of the nuclear plant is now in an operational testing stage, while nuclear fuel is scheduled to be delivered from Russia in the first quarter of 2020.[6]

The importance of the energy sector to Belarus’s overall economy is difficult to overstate. In fact, it is the key to its survival. The Belarusian state obtains a substantial share of its revenue from selling products derived from Russian crude, re-exporting Russian oil and from charging Russia a transit fee to send billions of cubic meters of gas a year to Ukraine and Europe through Belarus’s pipeline networks. The Belarusian Statistics Committee says Belarus makes $1.1 billion a year from selling refined oil products and $1 billion a year from sending Russian oil and gas to other countries.[7]

The Belarusian economy also benefits from Russian oil and gas in another way: The prices it pays for these commodities for its domestic use are much lower than the going rates internationally. And while Russia has periodically increased the prices, Belarus is still securing a favorable deal—although it protests every time there is an up-tick. Oil and gas–dependent economies like Belarus’s come with a serious downside, of course. Namely, fluctuations in global energy prices mean that Belarus can quickly go from being in good financial shape to having to scramble for revenue.

Russia’s Energy Ripple Effects on Belarus

Because Belarus’s economy is so dependent on Russian oil and gas, economic changes affecting its neighbor can spill over into Belarus, potentially with disastrous consequences. One poignant example involves the recent change in the way Russia taxes its oil industry. The shift has increased the price that Belarus pays for Russian oil, reducing its revenue. More detailed implications of this change on Belarusian state revenues are discussed below.

Belarusian-Russian energy relations have experienced dozens of ups and downs since the two countries became independent in the early 1990s. Although their energy disputes far outnumber similar Russian conflicts in this domain with Ukraine, the Moscow-Minsk standoffs mostly avoided spiraling out into major blow ups. The reason for this is tied to Belarus’s heavy economic dependence on Russia. Its neighbor is not only (essentially) the sole supplier of Belarus’s oil and gas but also its largest trading partner by far.[8] In addition, Belarus has been chronically indebted to Russia for its entire history as a sovereign state. Lacking the financial resources to provide the array of social services its citizens need or to make necessary structural improvements, it has often resorted to borrowing from Russia.

In recent years, Moscow has leaned harder on Minsk to take steps toward confederation that would hew to the Kremlin’s wishes. Belarus’s longtime leader, President Alyaksandr Lukashenka, has so far resisted moves that could undermine his country’s independence, however—such as allowing permanent Russian military bases on his country’s soil. Russia is keenly aware of Belarus’s important geopolitical location, bordering on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) right flank in Europe’s East. And the ongoing hostility between Russia and the West has encouraged the Kremlin to find new ways to shore up that strategic direction. If Russia and Belarus were to become a confederation, Russia could more easily deploy troops along Belarus’s border with the European Union.

The Belarusian economy enjoyed modest growth in the early 2000s. But the pace of expansion started slowing in 2014 and reached an alarming level of only 1.2 percent—almost no growth—in 2019.[9] Belarus’s status as both a petroleum-product importer and exporter means that a drop in oil and gas prices helps its non-petroleum sectors but also reduces the revenue it obtains from selling value-added petroleum products abroad.

Diversification Efforts Sputter

Aware of its vulnerability to Russian economic upheaval, Belarus has sought to diversify its economy as well as reduce its dependence on the eastern neighbor’s energy resources. But so far, those efforts have largely failed, and in many ways the government’s approach has defied economic logic, implementing certain polices that will actually make economic diversification more difficult. Rather than creating a fertile environment for a free-market economy, for example, it has been strengthening the state’s role in major economic segments.

Since the Belarusian economy relies so heavily on cheap Russian oil and gas, Minsk presumably has an overwhelming incentive to avoid any and all disruptive gas battles like the ones Ukraine has fought with Russia. But in fact, Belarus was subject to several such disputes in recent years. Indeed, it was actually the first country that the Kremlin opted to “punish” by cutting off its oil and gas supplies in February 2004.[10] The shutdown generated headlines at the time, although not nearly as many as when Moscow stopped pumping natural gas to Ukraine and Western Europe during a rancorous dispute with Kyiv nearly two years later. The 2005/2006 supply disruption left gas-short Europe shivering during the winter, and prompted European leaders to start looking for alternatives to Russian energy.

Moscow and Minsk sniped at each other about Russian oil and gas prices as well as Belarusian gas-transit fees on and off since becoming independent before a major dust-up arose. One reason their bilateral energy-related squabbles stayed in bounds for so long—as compared with the periodic Ukrainian-Russian disputes—was that Belarus never showed any signs of wanting to integrate with the West, unlike Ukraine. On the contrary, Belarus has, to date, joined every political-economic integrationist institution that Russia has proposed or supported, including the Customs Union and the subsequent Eurasian Economic Union (EEU).

Belarus and Russia began talking about political integration in 1999, when they signed the Union State treaty, pledging to take steps necessary to achieve this goal.[11] Not wanting to do anything that might discourage Belarus from pursuing eventual integration, Moscow gave Minsk favorable (highly subsidized) energy deals for five years. But disagreements over the terms of bilateral energy cooperation turned nasty in 2004. From that point on, Russia started taking a tougher line regarding mutual oil and gas talks.

Breaking with more than a dozen years of tradition, 2004 was significant in that it marked the first time Gazprom refused to sell gas to Belarus at subsidized prices—that is, below the international market rate. And since that time, Russia has had no further qualms about periodically reducing or cutting off gas to Belarus for up to weeks at a time, with the biggest flare-ups of this sort occurring in 2010 and 2017.

Faced with this new reality, Minsk has countered on a number of occasions by disrupting the delivery of gas that Russia sends through Belarus to Europe—Gazprom’s main market.[12] And in 2007, Belarus introduced a new retaliatory tactic: It began siphoning off some of the oil Russia was sending to European customers through the Druzhba pipeline, the main branches of which run across Belarus and Ukraine.[13]

Meanwhile, several recent energy developments are likely to sharply exacerbate Russia and Belarus’s petroleum-and-gas-sector disagreements going forward. First is Russia’s construction of new pipelines in the Baltic and Black seas (the latter, via Turkey) to deliver its gas to Europe without having to transit through Belarus and Ukraine. Lukashenka railed against Russia’s first trans–Baltic Sea pipeline—the 55 bcm Nord Stream One, built in 2007, which directly links Russia and Germany—because of the huge threat he recognized it posed to his country’s livelihood.[14] The Nord Stream Two pipeline, which mostly follows alongside its namesake predecessor, will double this export route’s annual capacity to 110 bcm. Russia promises Nord Stream Two will be completed in 2020. Once it comes online, it will make Belarus’s overland gas pipeline network even more dispensable, thus further reducing Minsk’s leverage in future gas disputes with Moscow.

Belarus gained an unexpected bargaining chip this past year when, in April 2019, Transneft sent millions of gallons of contaminated oil through the Druzhba pipeline, causing massive damage to Belarusian refineries and spoiling Russia’s reputation as a dependable supplier to Europe—but this leverage will be short-lived. Minsk has demanded more than three-quarters of a billion dollars from Russia for the revenue it lost when Trasneft had to shut down the pipeline to clean it. Although compensation is in the cards, Minsk is unlikely to obtain anywhere near the damages it wants. And once the issue is resolved, Belarus will lose a lot of the leverage it currently has to prod Russia into favorable energy-dispute fixes.

Oil Imports and Transit Rows

Belarus and Russia’s oil-import and oil-transit disagreements have become more contentious in the past five years as Russia’s own revenue picture has deteriorated. One factor in this deterioration has been lower global oil prices. For instance, the Russian economy shrank by 3.7 percent in 2015, when oil prices plummeted to their lowest since 2012, while inflation reached 12.7 percent.[15] Falling energy prices meant less money, which was exacerbated further by Western sanctions imposed on Moscow to punish it for its seizure of Crimea, its support for eastern Ukrainian separatists, and its overseas adventures in Syria and elsewhere. According to Russian President Vladimir Putin, over the past five years Russia lost $50 billion merely due to the sanctions—a substantial amount for the Kremlin to use for both domestic projects and foreign affairs.[16]

Looking for additional revenue anywhere it could find it, Russia asked Belarus to pay higher prices for oil in 2016. When Minsk balked, Russia reduced its oil exports to Belarus by 30 percent in the first quarter of 2017.[17] Although the reduction was temporary, it underscored the critical role that Russian oil plays in Belarus’s economy.

The Russian-operated Druzhba oil pipeline is a strategic asset and major revenue generator for both Russia and Belarus. In fact, a quarter of Russia’s total oil exports flow through the Druzhba. In return for allowing part of the pipeline to remain on Belarusian soil, Minsk receives below-market prices for oil for its domestic use, transit fees on EU-bound oil flowing through the Druzhba, as well as revenue from re-exporting Russian crude and selling refined products to neighboring countries.

Because Belarus’s economy is so closely tied to Russia’s, lengthy oil- or gas-supply disruptions can cripple it. During the 2016–2017 dispute, Mink tried offsetting the losses it was suffering from a 30 percent reduction in Russian supplies by importing crude through Black Sea ports in Ukraine and Baltic ports in Poland. But the higher oil prices and shipping expenses cost Belarus an additional $1 billion.[18] At one point, Belarus hoped to import oil through the planned Odesa–Brody Pipeline. But the project, which would have run from the Black Sea port of Odesa to the western Ukrainian city of Brody, near the Polish border, was shelved in 2013.

A positive energy-related development for Belarus’s economy is that a major retrofitting of its refineries is likely to be completed this year. Both were originally designed to handle the poor-quality crude that Russia produced during Soviet times. The upgrading, which began in 2017, will allow them to handle better-quality oil.

Nevertheless, an enormous cloud continues to hang over Belarus’s economic prospects, including when it comes to the long-term profitability of its refineries: the change in Russia’s oil tax law (analyzed in greater detail in the next section of this study).[19] Without some kind of relief from Moscow, Minsk is likely to take a huge hit to its economy, affecting what it can spend on health care, social programs, pensions and other important efforts. The problem is rooted in Russia’s decision to shift oil taxes from exporters to producers—that is, the companies that actually extract the oil. When Russian refineries protested that the higher taxes would hurt them by raising the cost of the crude they buy, the Kremlin gave them a tax rebate. Belarus, on the other hand, cannot afford to give its refineries a tax rebate—it would cost the government too much revenue. With the new tax regime in Russia, Belarus will be losing on average $17 per ton (assuming an oil price of $60 per barrel).[20] To try to recoup some of the revenue it is losing as a result of higher Russian crude prices and last year’s contamination of the Druzhba pipeline (described in detail in the following section), Belarus suggested increasing the tariff by 21 percent. In August 2019, Minsk increased the transit fee by 3.7 percent.[21] And the government is now considering adding an environmental tax to Russian oil transit in order to recoup the incurred costs.[22] Most recently, on January 30, 2020, Minsk announced that it would raise the tariff by an additional 6 percent, starting from February 1.

Two Unresolved Oil-Sector Spats

The two major still-unresolved oil disputes between Minsk and Moscow are 1) what to do about the revenue Belarus is losing from Russia’s oil-tax maneuver and 2) how much Russia should pay Belarus for its Druzhba contamination losses. Belarus not only wants Russia to come up with a way to reverse the oil-revenue shortfall it is experiencing from the tax change but also to compensate it for the revenue it has already lost as a result of the contamination accident. But the sides remain poles apart on the amount of reimbursement Minsk should receive.

Oil-Tax Reform Disagreement

Russia began changing the way it taxes oil in 2015, in response to a plunge in global prices and the sanctions the West imposed on it. It is gradually reducing its tax on oil exporters to zero while increasing its tax on producers.

Although the change is expected to generate an additional $23.6 billion a year for Russia’s budget by 2025, it jarred the oil industry by lowering its profit margins.[23] This was a problem not just for the industry, but also for the Russian government because the domestic oil sector needs to be healthy for Russia’s economy to thrive. The producer tax meant less money for Russian oil companies to spend on maintaining existing operations, bringing new fields to production, and expanding distribution networks. The government’s solution was to give the industry tax breaks for refinery modernization.

To maintain their profit margins, Russian producers began charging more for crude to offset the higher tax they were paying. Russian exporters, in turn, passed the higher cost on to Belarusian importers, slashing Belarus’s revenues. The shift in the oil-tax burden from Russian exporters to producers has been a huge financial blow to Belarus, costing it an additional $400 million in 2019.[24] Moreover, Minsk has also been unable to take advantage of the drop in Russia’s oil export duties because, as a member of both the Customs Union and the Eurasian Economic Union, it was exempt from the duties in the first place. Meanwhile, the refinery-modernization tax breaks that Russia gave its producers do not apply to Belarus, because its refineries are not Russian companies.

The Belarusian discontent over Russia’s tax reform led to another bilateral dispute at the end of 2019. The oil-import contract expired on December 31, 2019, and the parties could not find a compromise. As a result, on January 3, 2020, Russia cut direct oil supplies to Belarus while maintaining the transit through the country.[25] Belarus claims that its economy will lose $10.5 billion–$11 billion between 2019 and 2024. In recompense, Minsk demand from Moscow either yearly compensation for the losses or a $10 discount on imported oil. To date, the parties have agreed on a methodology for the compensation, although the actual amount that may be coming Belarus’s way is still subject to further negotiations.[26] The next round of talks is scheduled for February 1, 2020; and Minsk and Moscow have to additionally come to some agreement on the amount of compensation Belarus should receive for the contamination of the Druzhba pipeline in summer 2019.

With traditional suppliers such as Rosneft, Gazpromneft, Lukoil, Tatneft and Surgutneftegaz balking at offering Belarus a discount, Lukashenka started seeking alternatives to them both in Russia and abroad—something he has done in previous disputes, with no sustainable success. On January 4, 2020, Belneftkhim, the Belarusian state concern for oil and chemicals, announced it had signed a contract with Russneft for supply of 750,000 tons of oil for the Mozyr refinery.[27] But the contract is signed for only the first quarter of 2020, and even that volume will not suffice to fully supply Belarusian demand. Lukashenka’s efforts to find willing suppliers abroad has yet to yield any progress absent a small volume purchase from Norway. On January 21, the Belneftkhim refinery announced the purchase of 80,000 tons from Norway via the Lithuanian port of Klaipeda.[28]

Lukashenka’s government also addressed letters to Poland, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and the Baltic States, hoping to secure a commercially feasible supply contract. However, the talks with these suppliers have yet to yield any positive results. Poland was the first to disappoint Belarus, announcing that it was technically impossible to reverse the flow of the Druzhba pipeline.[29] The Kazakhstan option remains the only direction on which Belarus has had any success in talks, but even the Kazakhstani alternative comes with its own challenges. For instance, on January 21, Lukashenka complained that Moscow was not allowing Kazakhstan to use its territory for the transit.[30] And even if Belarus ultimately signs a deal with Kazakhstan, Minsk will have to pay Nur-Sultan[31] $5 a ton more than Russia’s price.[32] This would be a major increase for Belarus, given that it imports 18 million tons of oil a year for its domestic consumption. Belarus faced a comparable situation during a 2012 dispute with Russia. Azerbaijan and Venezuela were willing to sell it crude, but the cost would have been considerably higher than Russian oil.

Lukashenka seeks alternative supplies to gain a bargaining chip with Russia. In 2019, he sent a shot across Russia’s bow when he announced that Belarus was talking with Poland and the Baltic States about obtaining oil through the so-called Northern Route.[33] In addition, it was reported that Belneftkhim is trying to implore the United States to remove sanctions against it so it can import US oil.[34] The US Treasury Department placed sanctions on Belarus during the George W. Bush administration, in 2007. But the Barack Obama and Donald Trump administrations have waived the sanctions on a number of Belarusian energy enterprises since 2015. The most recent exemption, for 18 months, was provided on October 22, 2019.[35]

Another alternative is resurrecting the idea of the Odesa–Brody Pipeline—a possibility that Belarusian and Ukrainian officials discussed last November. Ukrainian officials said the sides actually established a joint commission to oversee the delivery of oil from Brody to the Mozyr refinery.[36]

The key to whether Belarus goes with an alternative, of course, is whether it is price-competitive with Russian supplies—a big “if.” Nonetheless, President Lukashenka rigorously rebuked the price competitiveness argument, claiming that he was not bluffing when he talked about alternative supply options. The Belarusian leader went further, saying that even though Saudi or US crude was more expensive, its quality was much better than Russian oil.[37]

Druzhba Contamination Dispute

On April 19, 2019, Belneftkhim announced a sudden deterioration in the quality of oil being imported to the Naftan and Mozyr refineries via the Druzhba pipeline.[38] On April 24, Belarus suspended the export of Russian oil to other countries, and Germany, Poland and Ukraine cut Russian oil imports within the next three days.[39] Tests of the oil transported by the Druzhba pipeline revealed it had higher-than-permitted levels of organic chlorides.

Belarus and Russia created a joint commission to determine how much compensation Minsk should receive from Moscow for its Druzhba export/transit losses and the damage to its infrastructure from the contaminated oil. But those talks have made little headway to date because of the huge gap between what the sides believe the figure ought to be.

The debacle has also hurt Russia’s credibility in Belarus and Europe. Until the contamination occurred, Russia enjoyed the reputation of a dependable oil supplier to the continent. In the six decades that the Druzhba pipeline has been operational, there had not, until now, been any similar incidents that might call into question the reliability of the pipeline.

Gas Transit-Fee Rows

The 39 billion cubic meters of Russian gas that Belarussian pipelines deliver to Europe annually is a mutually beneficial business for both countries.[40] It accounts for a fifth of the gas that Russia delivers to Europe, and it generates half a billion dollars in transit-fee income for Belarus. Although this amount does not constitute significant part of Belarusian budget revenues, Russian gas transit does equip Minsk with additional leverage in gas import negotiations with Gazprom.

Belarus imports 20 bcm of Russian gas a year for its own use.[41] Belarus has no domestic oil or gas reserves to speak of, but its economy is highly energy-intensive. So it has no choice but to import Russian gas, since it is the cheapest available. Russia gave Belarus a huge price discount until their first energy dispute in 2004. But Gazprom has increased the price of Belarus’s supply several times since then.

Belarus’s Weak Negotiating Leverage Vis-à-Vis Russia

The two partners have had three major transit-fee rows since 2004. Each time, Russia demonstrated its stronger negotiating position over Belarus by reducing the amount of Europe-bound gas flowing through Belarusian pipelines for a few weeks at a time. Besides failing to find a price-competitive alternative to Russian gas, Belarus has tried—unsuccessfully—to reduce its domestic gas consumption, which has held steady at 18–19 bcm per year since 2004.[42]

The bottom line is that natural gas continues to be vital to Belarus’s economy and its people’s standard of living. As an example, its state-owned utility, Belenergo, burns gas to generate 97 percent of its electricity.[43] Gas is also the country’s main fuel for heat. Although total energy consumption in the country decreased rapidly between 2012 and 2015, it has remained stable since then. While its per capita natural gas consumption remains twice as high as the average figures in Europe—1,880 versus 903 cubic meters, respectively.[44]

Belarus is the only Eurasian Economic Union country that imports gas directly from Russia, and it pays the lowest price of any member— $127 per 1,000 cubic meters.[45] Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, members that do not border Russia, pay $165. By comparison, European countries pay $230–$250 per 1,000 cubic meters.[46] Before a meeting between Presidents Lukashenka and Putin on December 6, 2019, the Belarusian leader even mulled accepting a price tag of $110 for Russian gas.[47]

Belarus has reciprocated Russia’s price generosity by charging Gazprom the lowest gas transit fee of any EEU country. But it complains that the price Russia charges it still violates the economic bloc’s fair-competition provisions. As proof, Lukashenka notes that gas in Russia’s Smolensk Oblast, which borders Belarus, costs only $70 per 1,000 cubic meters.

Since Belarus and Russia’s first energy spat in 2004, Gazprom has increased Belarus’s gas prices to near the bottom of the range it charges European countries, minus delivery costs. It has also built other pipelines to deliver its gas to Europe—namely, Nord Stream and TurkStream—diminishing Minsk’s bargaining power in price negotiations. Meanwhile, Russian oil and gas companies have acquired sizable stakes in Belarusian energy operations, further reducing Minsk’s leverage in its oil and gas dealings with Moscow. As one crucial example, unlike the situation in Ukraine, Belarus does not own the pipelines that carry Russian gas to Europe—Russia does.

Gazprom has also weakened Belarus’s bargaining position by creating a liquefied natural gas (LNG) receiving terminal and a floating regasification unit in Russia’s European exclave of Kaliningrad Oblast as well as by expanding its gas storage facilities there. This makes the detached Russian territory less dependent on gas from Russia proper having to pass through Belarus.[48]

External and Market Forces Playing in Belarus’s Favor

Although Russia’s new Nord Stream Two and TurkStream pipelines to Europe will further reduce Minsk’s leverage in bilateral gas-price negotiations with Moscow, Belarus still has some cards to play, thanks to several macroeconomic and geopolitical developments.

First of all, the European Union recently dealt Russia a setback that will require it to continue using Belarusian pipelines to deliver a significant proportion of its gas exports to Europe. Namely, an EU court rejected Gazprom’s demand that it be allowed to use 100 percent of the capacity of a pipeline link between the Nord Stream One pipeline, which originates in Russia, and overland European pipelines serving Germany and the rest of Europe. The overland link around which the EU case revolved, the Opal pipeline, connects Nord Stream, which runs from Russia under the Baltic Sea to Germany, with Germany’s domestic network as well as serves several other European countries.

Russia is now concerned that the court decision on Opal will set a precedent for links between its Nord Stream Two pipeline, which is supposed to be completed in 2020, and other pipelines in Germany and beyond. Until Gazprom sorts out the court decision, it will likely continue having to send gas through Belarus (and Ukraine)—or at least keep that transit corridor in reserve.

Another reason Gazprom is likely to continue using Belarus’s pipeline network is that it has a major stake in—and thus is profiting from—one of the country’s two pipeline companies, the aforementioned gas transit infrastructure operator Beltransgas. Russia has no incentive to walk away from this profitable business venture at this time.

A geopolitical factor figuring into Gazprom’s calculus on whether to continue using Belarusian pipelines is Russia and Ukraine’s gas pipeline standoff. As a result of the increasingly fractious relations with its once-friendly neighbor, Russia has been rushing to finish Nord Stream Two and recently inaugurated TurkStream Two, both of which bypass Ukrainian territory. However, until Nord Stream Two begins delivering an additional 55 bcm per year of Russian gas to Europe directly, Gazprom will need every alternative it has to supply the continent, including its Belarusian pipelines.

Another consideration in Russia’s calculus on whether to continue using Belarus as a transit country is the decline in Europe’s own gas production, mainly in the North Sea and the Dutch Groningen field. Belarus’s Yamal-Europe pipeline annually delivers 32 bcm of Russian gas to northwestern Europe—the very region where the North Sea and Groningen production is declining.

Gazprom knows that if it fails to keep serving this market, liquefied natural gas companies are likely to eat into some of its share. So far, the state-owned gas giant has maintained its dominance, with pipeline gas still accounting for 86 percent of EU imports. But the United States, Qatar and even Russia’s Novatek are trying to boost LNG sales to Europe, threatening Gazprom’s market share.[49]

US LNG exports, in particular, have soared in the past two years, now making the United States the world’s third-largest exporter. In 2018, more than 70 percent of US LNG ended up in Asia, versus 13 percent in the EU.[50] But the situation changed dramatically in 2019. Price differences between LNG going to Asia and liquefied gas supplies destined for Europe fell. Meanwhile, US companies collectively added more LNG-exporting capacity, and US and EU leaders pledged to strengthen their strategic cooperation, including in energy. The result is that Europe now obtains 32 percent of the United States’ total LNG exports.[51]

Novatek’s Europe incursion has been particularly nettlesome for Gazprom, since it is a Russian company. Novatek is today Russia’s second-largest gas exporter and the largest exporter of Russian LNG. It sells mainly to Europe, despite the fact that the company’s Yamal LNG terminal is located in Russia’s Far East. Novatek has begun using next-generation LNG ships that can traverse the Arctic Ocean even in winter. Three of Yamal LNG’s trains (liquefaction and purification facilities) are currently operational, and, although with delay, it plans to finish the fourth unit in the first half of 2020.[52] Furthermore, Novatek and its partners are about to make a final investment decision on the construction of the three-train Arctic LNG 2 production project.[53] This means Gazprom will have to keep on its toes to prevent Novatek from whittling away at its market share in the world’s two most lucrative gas markets—Asia and Europe. One way it plans to do this is to increase its own LNG capacity from the current 16.5 million tons annually to 19.8 million within five years.[54]

Thanks at least in part to all these geo-economic and market-force trends working in Minsk’s favor, on December 31, 2019 (only few hours before their previous natural gas deal expired), Belarus and Russia agreed to extend their gas contract for one more year.[55]

Enter a Nuclear Power Plant

Natural gas’s stranglehold on Belarusian power production will begin diminishing next year, when Russia’s Rosatom commissions Belarus’s first nuclear plant. The facility, financed by $10 billion in Russian loans, is in the northwestern Belarusian city of Astravets. Its capacity of 2.4 gigawatts will be enough to power 1.7 million homes.

The commissioning will be the culmination of nine years of work. The facility’s first reactor is expected to be operational in early 2020.[56] The plant will boost Belarus’s state revenues by giving it the ability to sell even more electricity to neighboring countries. Belarus imported electricity from Russia until 2018. But that year, it became self-sufficient in electricity generation for the first time, even allowing it to sell 1 billion kilowatt hours of excess power to, primarily, the Baltic States.[57] The new nuclear plant, which alone will generate 17 billion kilowatt hours,[58] will enable Belarus to export even more, particularly to Ukraine and Lithuania. Indeed, the Ukrainian parliament set the stage for buying Belarusian electricity in September 2019 by replacing a law that had heretofore prevented such imports.

With memories of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in Soviet Ukraine still fresh, however, many people living in countries near Belarus have opposed the Astravets plant. This has been especially the case in Lithuania, whose leadership and regular citizens alike have lambasted the fact that the plant is being built only 50 kilometers from their country’s capital, Vilnius. To underscore its unhappiness, Lithuania at one point warned it may not to purchase any Belarusian electricity. It also threatened to stop allowing its power-transmission lines to carry Belarusian-produced electricity to Estonia and Latvia. Ironically, Lithuania is already importing Russian gas through its first LNG terminal at Klaipeda.[59]

In 2019, Belarus exported 2 billion kilowatt hours of electricity to Ukraine and the three Baltic States, which constituted 80 percent of its total power exports. Currently, Belarus’s electricity trade with the Baltics is conducted via Nord Pool, a European power exchange platform mainly used by Scandinavian and Baltic countries.[60] No cross-border electricity transmission link exists between Belarus and Latvia, so generally exports must first pass through the Lithuanian grid. Nonetheless, Riga has signaled that it would import electricity from the Astravets nuclear plant even if Lithuania refuses to permit its transmission lines to be used to deliver that power. Without finally building direct Belarusian-Latvian transmission line connections and other necessary infrastructures to facilitate the electricity trade, Estonia and Latvia could theoretically import Belarusian power through Russia.

In addition to the transit bottlenecks, Minsk’s electricity exports face serious competition from Russian suppliers in the region. To address this market weakness, Belarus has partnered with Chinese companies and financial institutions. According to recent reports, Chinese State energy company Power China and its subsidiary North China Power Engineering (NCPE) will be helping Belarus to sell electricity from its nuclear plant. NCPE, which has already constructed and modernized other elements of Belarus’s electricity infrastructure, is contracted to build 23 transmission and inter-connection facilities linked to the Astravets nuclear plant. Belarus has also received a $5 billion loan from the Export–Import Bank of China for this project.[61]

Conclusion

It is difficult for countries that must import oil, natural gas and other power-generating commodities to achieve the energy security their economies need. Belarus is a prime example. Its lack of oil and gas reserves has made its economy dependent on energy from its hydrocarbon-rich, internationally ambitious neighbor, Russia. Painfully aware of this vulnerability, landlocked Belarus has tried but failed to diversify its economy. It continues to derive much of its revenue from selling value-added products that its two refineries make from Russian crude and from the transit fees it charges to deliver Russian oil and gas to Europe. This means Belarus’s energy security continues to depend on a complex web of relations with Russia.

Part of the complexity stems from the fact that Belarusian-Russian energy relations have never been based on business interests alone. They have been linked to other issues as well, including Moscow’s desire for the two countries to be politically and economically integrated.

With Belarus so dependent on Russian oil and gas, and Moscow wanting to use its petroleum muscle to bend Minsk to its political will, the two have become embroiled in off-and-on energy disputes for 15 years. Despite Russia holding most of the cards, in the majority of cases Belarus found ways to obtain outcomes it could live with. The resolutions always failed to last, however. Within a few years, another dispute would pop up, Belarus losing additional ground with each settlement. Some of the past resolutions have created long-term problems for Minsk. This is particularly true of agreements that involve Russian companies taking over pieces of Belarus’s critical energy infrastructure in lieu of cash payments.

Belarus and Russia have been working on political and economic integration for 20 years, but the talks have made little headway to date. Then–Russian prime minister Dmitry Medvedev inserted himself into the process in 2018 to try to kick-start the negotiations again. But whether his initiative leads to a timely resolution of the issues preventing further integration remains to be seen.

A lot is riding on the results of those talks, not just for Belarus and Russia but for the European Union, too. The Russian economic publication Kommersant reported in December 2019 that Moscow and Minks are working on establishing joint markets and even a joint oil and gas regulatory agency by 2021. Yet, two issues could stall such integration efforts: the price Belarus pays for Russian gas and the compensation it is demanding for the Russian oil-tax changes that have hammered the Belarusian economy.[62]

One implication of a Belarus-Russia confederation would be that Moscow could deliver its oil and gas directly to the EU without using a middle man, since it would have greater control over its pipelines in Belarus than at any time since the two countries’ independence. Another energy-related benefit deeper integration would bestow on Moscow would be more ability to dictate how Belarus regulates its oil, gas and electricity markets. These developments would offer Russia more control over its oil and gas transit costs to Europe, increasing its clout in regional energy geopolitics.

Integration would create both pluses and minuses for Belarus. On the positive side, Russia would probably pump more money into Belarus’s chronically capital-poor economy. But in exchange for the largesse, Russian companies would likely take over more of Belarus’s key energy assets.

Despite plans to bring the Nord Stream Two and TurkStream gas pipelines online in the near future, for now Russia continues to need Belarus’s energy-transit link to Europe. This will remain the case unless major geopolitical changes envelop the region or there is regime change in Minsk or Moscow. To decrease its dependence on Russia, Belarus must diversify its economy and its sources of energy supplies. It has failed to achieve both objectives in the past, and the task is unlikely to prove any easier going forward.

Notes

[1] “Belarus-Country Profile,” The Observation of Economic Complexity, https://oec.world/en/profile/country/blr/#Exports.

[2] Slavneft Official Website, https://www.slavneft.ru/eng/company/geography/mozir/.

[3] European Council, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/infographs/energy/bloc-2c.html.

[4] Global Intelligence Report, “Yamal-Europe Natural Gas Pipeline,” Oilprice.com, February 14, 2011, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Natural-Gas/The-Yamal-Europe-Natural-Gas-Pipeline.html

[5] Elena Mazneva, “Gazprom annexes Belarus to Russia,” December 29, 2011, Vedomosti.ru, https://www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2011/12/30/igra_na_trubah.

[6] “Nuclear fuel for BelAes to be delivered in 1Q of 2020,” Sputnik Belarus, December 19, 2019, https://sputnik.by/economy/20191219/1043523369/Yadernoe-toplivo-na-BelAES-zavezut-v-pervom-kvartale-2020-goda.html.

[7] “How much does Belarus make in oil exports,” Express.by, April 27, 2019, https://ex-press.by/rubrics/ekonomika/2019/04/27/skolko-belarus-zarabatyvaet-na-tranzite-rossijskoj-nefti-menshe-chem-na-korovax.

[8] Russia is the largest trading partner of Belarus, whereas Belarus is Russia’s fourth-largest trading partner. Trade turnover between the two countries equaled $21 billion in 2019. See: Daniel Workman, Worlds Top Exports, January 2, 2020, https://www.worldstopexports.com/russias-top-import-partners/.

[9] “Economy of Belarus grew 1.2% in 2019,” Belta Belarus, January 16, 2020, https://www.belta.by/economics/view/vvp-belarusi-v-2019-godu-vyros-na-12-376167-2020/.

[10] Sergei Danilochkin, “Belarus: Moscow And Minsk Back Down From Gas Crisis As Temporary Supplies Resume,” Radio Free Europe, February 19, 2004, https://www.rferl.org/a/1051606.html.

[11] Belarus Ministry of Foreign Affairs, https://mfa.gov.by/en/courtiers/russia/.

[12] Gazprom’s total exports equaled 239 bcm in 2019, excluding the sales of gas purchased by the company abroad. Of that volume, 199 bcm was delivered to Europe. See: “ ‘Gazprom’ konkretiziroval itogovyye dannyye po dobyche gaza v 2019 godu,” Interfax, January 2, 2020, https://www.interfax.ru/business/690081.

[13] “Russia oil row hits Europe supply,” BBC News Service, January 8, 2007, https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6240473.stm.

[14] At one point, Lukashenka called the first Nord Stream pipeline “the most idiotic project” the Russians were pursuing. “Lukashenko names the most idiotic project of Russia,” Lenta.ru, January 14, 2007, https://lenta.ru/news/2007/01/14/project/.

[15] “Upshot of Russian Economy in 2016: Surplus shading into zeitnot” Interfax, December 29, 2016, https://www.interfax.ru/business/543640.

[16] Elena Gosteva, “Putin has calculated the costs: Who lost more?” Gazeta.ru, June 20, 2019, https://www.gazeta.ru/business/2019/06/20/12429169.shtml.

[17] “Russia reduces oil supply to Belarus by 30%,” Neftegaz.ru, April 3, 2017, https://neftegaz.ru/news/transport-and-storage/211414-rossiya-v-1-kvartale-2017-g-snizila-postavki-nefti-v-belorussiyu-na-30-i-dumaet-chto-delat-dalshe/.

[18] “Russia and Belarus regulate the gas crisis,” Neftegaz.ru, April 4, 2017, https://neftegaz.ru/news/politics/211387-nuzhno-idti-na-ustupki-rossiya-i-belorussiya-uregulirovali-neftegazovyy-spor-i-dogovorilis-o-sozdani/.

[19] “Russia’s Oil Sector Is Facing A Massive Tax Overhaul,” Oilprice.com, June 11, 2018, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/Russias-Oil-Sector-Is-Facing-A-Massive-Tax-Overhaul.html.

[20] Olga Dolgaya, “Andrey Buynakov: Politics of sales are changing,” Belchemoil.by, November 27, 2019, https://belchemoil.by/news/ekonomika/andrej-bunakov-politika-prodazh-menyaetsya.

[21] “Belarus increases the transit fee for Russian oil,” Belsat.eu, August 7, 2019, https://belsat.eu/ru/news/belarus-povyshaet-tarif-na-tranzit-rossijskoj-nefti-no-ne-na-tak-mnogo-kak-hotelos-by/.

[22] Aleksandr Yarevich, “Has Belarus levied environmental tax on oil transit?” Naviny.by, January 13, 2020, https://naviny.by/article/20200113/1578926895-belarus-vvela-nalog-na-tranzit-nefti-kasaetsya-li-rossii.

[23] “Budget overhaul: How much will gasoline cost?” Gazeta.ru, October 28, 2019 https://www.gazeta.ru/business/2019/10/28/12782102.shtm.

[24] “Tax overhaul may cost Belarusian budget $400 million,” Komsomolskaya Pravda, October 10, 2019, https://www.kp.by/online/news/3634899/.

[25] “Russia suspends oil supplies to Belarus,” RIA Novosti, January 3, 2020, https://ria.ru/20200103/1563086307.html.

[26] “Moscow and Misnk agree the methodology of compensation,” RBK, December 18, 2019, https://www.rbc.ru/politics/18/12/2019/5df7491e9a79476e63ff800e.

[27] “Supply request for oil from Russia processed for Russneft and Neftis,” Interfax Belarus, January 4, 2020, https://interfax.by/news/policy/ekonomicheskaya_politika/1269577/.

[28] “Belarus starts buying oil from Norway,” Korrespondent.ru , January 21, 2020, https://korrespondent.net/business/economics/4184591-belarus-nachala-zakupat-neft-u-norvehyy.

[29] “Polish operator assesses possibility of oil supply to Belarus via Druzhba,” RIA Novosti, January 14, 2020, https://ria.ru/20200114/1563417715.html.

[30] “Lukashenka: Russia does not allow Kazakstan to supply oil to Belarus,” RIA Novosti, January 21, 2020, https://ria.ru/20200121/1563671127.html.

[31] Kazakhstan’s capital city of Astana was renamed Nur-Sultan in 2019.

[32] “Kazakhstan’s dilemma: How to sell oil to Belarus while not angering Russia,” Sputnik.by, October 28, 2019 https://sputnik.by/columnists/20191028/1043082445/Kazakhstanskaya-dilemma-prodat-neft-Minsku-i-ne-possoritsya-s-Moskvoy.html.

[33] “Belarus is seeking to buy U.S. crude oil”, Radio Free Europe, August 22, 2019, https://www.rferl.org/a/belarus-lukashenka-us-oil-purchase-russia-reliance/30124113.html.

[34] “Belarus has intensified efforts to lift us sanctions”, Belarusinfocus.info, August 22, 2019, https://belarusinfocus.info/belarus-west-relations/belarus-has-intensified-efforts-lift-us-sanctions-and-diversify-foreign,

[35] “Belarus Sanctions Regulation,” The US Treasury, October 22, 2019, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/Documents/belarus_gl2g.pdf.

[36] “Minsk seeks to import oil via Odessa-Brody route,” Oilcapital.ru, November 25, 2019, https://oilcapital.ru/news/export/25-11-2019/minsk-hochet-poluchat-neft-po-marshrutu-odessa-brody.

[37] “This is not a bluff: Lukashenko on alternative oil import options,” January 24, 2020, https://www.belta.by/president/view/eto-ne-blef-lukashenko-rasskazal-o-vidah-na-alternativnye-postavki-nefti-377114-2020.

[38] “Belarusian oil refinery blames Russia for the oil quality,” UAWire, April 23, 2019, https://uawire.org/belarusian-oil-refinery-blames-russian-oil-for-the-equipment-damage.

[39] “Belarus has stopped exporting oil to its neighbours”, Currenttime TV, April 23, 2019, https://www.currenttime.tv/a/belarus-petrol-export/29899296.html.

[40] “Gazprom expects to maintain gas transit through Belarus at 39.3 bcm in 2018-2019 – report,” Interfax, June 15, 2018, https://www.interfax.com/newsinf.asp?pg=5&id=838995.

[41] “Russian, Belarusian ministers to discuss gas price next week,” TASS, November 6, 2019, https://tass.com/economy/1087306.

[42] BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019, https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2019-full-report.pdf.

[43] “Belarus-Addressing challenges facing the energy sector,” World Bank, June 1, 2006, https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/239061468004774448/Main-report.

[44] “Energy Consumption in Belarus,” World Data, https://www.worlddata.info/europe/belarus/energy-consumption.php.

[45] “Russia Gazprom cuts gas price for Kyrgyzstan,” Reuters, April 1, 2016, https://af.reuters.com/article/commoditiesNews/idAFL5N1742LF.

[46] “Gazprom may increase gas output by 80-115 bcm by 2035,” TASS, February 25, 2019, https://tass.com/economy/1046377.

[47] “Lukashenka: It is not Minsk’s fault,” Oilcapital.ru, December 6, 2019, https://oilcapital.ru/news/markets/06-12-2019/lukashenko-minsk-ne-vinovat.

[48] “Gazprom brings energy security of Kaliningrad Region to new level,” Gazprom, January 8, 2019, https://www.gazprom.com/press/news/2019/january/article472626/.

[49] “Liquefied gas report,” European Commission, August 8, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/oil-gas-and-coal/liquefied-natural-gas-lng.

[50] The US Energy Department, LNG Report, March 3, 2018, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2018/03/f49/LNG%20Monthly%202017.pdf.

[51] “U.S-Europe LNG trade,” European Commission, November 19, 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/eu-us_lng_trade_folder.pdf.

[52] “Troublesome start for first Arctic LNG plant manufactured in Russia,” The Barents Observer, January 23, 2020, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/industry-and-energy/2020/01/troublesome-start-first-arctic-lng-plant-made-russia.

[53] “2019 Rewind: Year of FIDs,” Oil & Gas 360, January 2, 2020, https://www.oilandgas360.com/https-www-lngworldnews-com-2019-rewind-year-of-fids/.

[54] “Arctic LNG,” Novatek, https://www.novatek.ru/en/business/arctic-lng/.

[55] “Kontrakty na postavku gaza v Belarus’ i tranzit cherez territoriyu respubliki prodleny do 2021 goda,” Gazprom, December 31, 2019, https://www.gazprom.ru/press/news/2019/december/article497273/.

[56] “Russian built nuclear power plant in Belarus nears completion,” Emerging Europe, September 27, 2019, https://emerging-europe.com/news/russian-built-nuclear-power-plant-in-belarus-nears-completion/.

[57] Belarus consumed 37 gigawatt hours (GwH) of electricity in 2018 and exported 1 GwH. See: “Electricity export from Belarus increases sevenfold in 2018,” Belmarket.by, February 23, 2019, https://www.belmarket.by/v-2018-godu-eksport-elektroenergii-iz-belarusi-vyros-bolee-chem-v-7-raz.

[58] “Will it be possible to consume electricity generated from BelAes in domestic market?” UDF.by, September 25, 2019, https://udf.by/news/main_news/199606-udastsja-li-osvoit-jelektrojenergiju-belajes-na-vnutrennem-rynke.html.

[59] “Presidential aide calls for not using Klaipeda LNG terminal for Russian gas imports,” Baltic Times, October 24, 2019, https://www.baltictimes.com/presidential_aide_calls_for_not_using_klaipeda_lng_terminal_for_russian_gas_imports/.

[60] “Belarus names the conditions for direct electricity supply to Latvia,” Sputnik News, November 27, 2019, https://lv.sputniknews.ru/economy/20191127/12823409/Belarus-nazvala-uslovie-stroitelstva-LEP-dlya-pryamykh-postavok-elektroenergii-v-Latviyu.html.

[61] “Chinese companies help Belarus to sell Astravets power,” Baltic Times, December 12, 2019, https://www.baltictimes.com/chinese_companies_help_belarus_to_sell_astravyets_power/.

[62] “Belarus and Russia have not agreed on gas price yet,” Komsomolskaya Pravda, November 29, 2019, https://www.kp.by/online/news/3689276/.