Chasing the Professor: A Portrait of Jemaah Islamiyah’s Upik Lawanga

Chasing the Professor: A Portrait of Jemaah Islamiyah’s Upik Lawanga

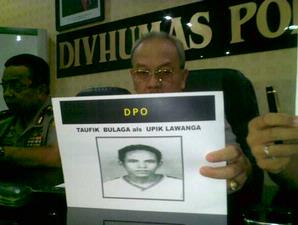

Taufik Buraga (a.k.a. Upik Lawanga) is a 34-year old high school-educated Indonesian jihadi from the small neighborhood of Tanah Runtuh, Poso on the island of Sulawesi (once known as Celebes). [1] He currently ranks as the foremost Jemaah Islamiyah (JI)-affiliated bomb expert. Since he set up shop on the island of Java in 2009, he has begun leading small-scale terrorist networks in bomb attacks.

Upik Lawanga specializes in low-yield “booby trap” explosive devices, including bombs that can be concealed inside flashlights, bombs that explode when doors are opened and thermos bombs that explode when the lid is opened. Because of his expertise, his apprenticeship under the late Malaysian national Dr. Azahari Husin, and his work instructing members of his own local networks in the craft of bomb-making, Lawanga has earned the nicknames “Prof (short for “Professor)” and “Poso’s Azahari.”

In 2009, Upik Lawanga was identified by Ansyaad Mbai, the head of the Indonesian Security Ministry’s Anti-Terrorism Agency, as one of three continuing dangers in Indonesia along with the late Dulmatin (see Militant Leadership Monitor, March 2010) and the now captured Umar Patek (see Militant Leadership Monitor, April 2010). In June 2011, Lawanga was listed as one of the Indonesian Police’s Ten Most Wanted (Detik News [Jakarta], June 15, 2011). Lawanga was most recently believed to be hiding in Kebonagung, north of Solo, or in one of Yogyakarta’s regencies. On July 19, 2011 two Densus 88 squads and a Yogyakarta Mobile Police Brigade conducted operations to search for him in those locations. Although they did not find Lawanga, they did arrest seven people in Yogyakarta and five people in Central Java who were alleged to be affiliated with his network (Pontianak Post [Jakarta], July 20, 2011).

Back in Poso, Upik Lawanga’s parents were “getting sick” upon hearing the news about their son’s bombings. In 2009, Lawanga’s older brother called on him “to surrender to security forces… in order for their family to have quiet.” Lawanga’s wife and young son are reportedly living in Morowali, one of Poso’s neighboring counties (Tempointeraktif, August 2, 2009).

The Origins of Lawanga’s Militancy

Upik Lawanga’s childhood neighborhood in Poso, called Tanah Runtuh (meaning “fallen earth,” referring to a landslide that occurred there in 1998), was home to a prominent religious leader, Haji Adnan Arsal, who worked in the local government’s religious affairs office. Arsal also operated as a JI recruiter and organizer in the wake of a massacre of Muslim students at the hands of Christians at the Walisongo Pesantren (madrassa) in 2000. Numerous students who survived the massacre were provided shelter and schooling by Arsal in Landangan, a town nine kilometers from Poso (Kabar Indonesia, January 25, 2007). It was in this milieu of inter-religious strife that Lawanga became enmeshed in jihad in Poso. He then became a member of what would later become the Tanah Runtuh group.

The first major attack involving Upik Lawanga-designed bombs occurred on May 28, 2005 when two potassium-chloride, Trinitrotoluene (TNT) and sulfur-filled pipe-bombs detonated at Tentena market in Central Sulawesi. The attacks, targeting Christian shoppers, killed 22 people and wounded more than 40 (AP, May 28, 2005). Based on police records, the two bombs were the largest explosions recorded in the history of Poso’s Christian-Muslim conflict, which started in 1998. The bombs were strategically placed 20 meters from each other in the busiest areas of the market and detonated 15 minutes apart from each other. A suspect called Sarjono (a.k.a. Paiman) was arrested by Indonesian police on January 11, 2007. During his subsequent interrogation, Paiman admitted to working with Lawanga to prepare several attacks in Poso. He purportedly provided Lawanga with the detonator for a bomb in the town of Tentena in Central Sulawesi Province.

Another Poso native, Amril Ngiode, was imprisoned for 15 years in 2007 for his involvement in the twin Tentena bombings. In his trial, Ngiode detailed how he aided Lawanga in assembly of the explosive devices: “He [Upik Lawanga] filled casings with TNT and sulfur. I helped stamp the powder mix with a wooden stick.” Ngiode added that a wooden implement was preferred over an iron equivalent since the heat caused by the friction could set off the bomb prematurely (Jakarta Globe, August 24, 2010).

Botched Capture and Flight to Java

If Densus 88 had not botched an attempt to capture Upik Lawanaga in 2006, his career may have ended there and the lives of his future victims may have been spared. In May 2006, four Densus 88 officers on two motorcycles went into Lawanga, the eponymous district north of Poso where Upik Lawanga then lived. Their goal was to arrest him outside of the Nurul Iman Mosque after morning prayers. The officers immediately handcuffed and arrested Lawanga as he left the mosque, but Lawanga shouted for help. One person ran out to bang on an electricity pole causing a crowd of people to come to the scene and aid Lawanga. Lawanga, according to the neighborhood leader of his community in Poso, always behaved well toward his neighbors and relatives and was considered a decent man amongst his people (Tempointeraktif, August 2, 2009).

After the crowd arrived, the Densus 88 officers fired warning shots in the air, but, overwhelmed, they then panicked and departed, leaving their motorcycles and a handcuffed Upik Lawanga behind. The angry crowd burned the two motorcycles and beat up one of the officers, leaving him wounded and later hospitalized (Kompas, May 29, 2006). That afternoon, the police chief of Poso visited the neighborhood with fellow officers to calm down the crowd and explain to them why Lawanga was a terror suspect. The crowd reacted by hurling stones at the police vehicle that was protecting the officers. The officers returned to their headquarters in Poso without Lawanga (Kompas, May 9, 2006).

In 2006 and 2007, various pipe bombs designed to be thrown like firecrackers and cardboard box bombs designed to detonate when opened were used against police officers in Poso. While there is no definitive link to Upik Lawanga, those devices are typical of his style. On September 9, 2006, Lawanga is reported to have made the flashlight bomb that a motorcyclist placed on the porch of a resident in Kawua whose house was located several hundred meters from Armed Forces’ Poso Battalion 714 (Tempointeraktif, April 15, 2011). When a 20-year old neighbor picked up the flashlight and turned it on, the flashlight exploded and killed her (Jakarta Post, October 9, 2006).

As of January 2008, Upik Lawanga was still believed to be in Central Sulawesi Province, but by February 2009 he is believed to have traveled to Bekasi, West Java to meet with the late Noordin Top Muhammad (Manado Post, July 20, 2011). Less than six months later, Lawanga is believed to have co-assembled the bombs that exploded in the JW Marriott and Ritz-Carlton hotels in South Jakarta on July 17, 2009 which killed nine (Reformata, August 19, 2009; Jakarta Post, July 29, 2010). No other major attacks were attributed to Lawanga from 2009 until 2011, when a series of parcel bombs struck targets in Jakarta.

Parcel Bombings

The evidence from the circuits, materials, manufacturing techniques and targets of three parcel bombings in Jakarta on March 15, 2011, led police to suspect Upik Lawanga. Police believed that either Lawanga himself or his disciples were behind the attacks, which were the first of their kind in Indonesia.

One of the targets in the parcel bombings is hardly surprising given Upik Lawanga’s previous run-ins with Densus 88, his record for attacking Christians during the Poso conflict and JI’s overall contempt for Densus 88. In the evening of March 15, 2011, a parcel bomb arrived at the offices of the Badan Narkotika Nasional (National Narcotics Agency) and was addressed to its chief, Brigadier General Goris Mere, a Christian and a former high-ranking officer in Densus 88 with a record for leading a number of successful raids against terrorists in Indonesia.

Upik Lawanga may have selected Brigadier General Mere as a target in response to a verbal order from JI founder Abu Bakar Baa’syir. During Baa’syir’s preliminary terror trial in the South Jakarta District Court in February he stated: “Densus 88… is dominated by Christian officers led by Goris Mere… Basically, Densus 88 is the tool of America and Australia whose goals are to eliminate the warriors who fight for Islamic Shari’a” (Jakarta Globe, March 15, 2011).

A parcel that exploded earlier in the day on March 15, 2011 was addressed to Ulil Abshar Abdalla, an outspoken critic of hardline Islamist groups, the founder of the Liberal Islam Network and a senior member of Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s Democratic Party—and sent to the office where Abdalla formerly worked at the Institute for Studies on Free Flow of Information (ISAI). Unlike the bomb sent to Brigadier General Mere, which was detected and defused, the parcel to Abdalla blew off the arm of the police officer who opened it. The bombs sent to Abdalla and Brigadier General Mere were both packaged in a book called Mereka Harus Dibunuh Karena Dosa-dosa mereka Terhadap Islam dan Kaum Muslimin (They Must be Killed for their Sins Against Islam and Muslims) (Jakarta Post, March 16, 2011).

The third parcel bomb was addressed to and sent to the house of Yapto Soerjosoemarno, the chairperson of the Pemuda Pancasila (Pacansila Youth Movement), and was contained inside a book titled Masih Adakah Pancasila (Does Pancasila Still Exist)? [2] The bomb to Soerjosoemarno, which was detonated using a three-wire circuit and a 3.7 volt battery from a Nokia 3315 cell phone, had the “signature” of Upik Lawanaga’s bombs and reinforced the police’s suspicion that Lawanga was involved (Manado Post, July 20, 2011).

Conclusion

Upik Lawanga has neither the pedigree of high-profile Indonesian terrorists, such as Patek or Dulmatin, whose jihadi careers began fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan, nor is he a “mastermind” like Noordin or Azahiri Husin. He is also not an ideological leader like Baa’asyir. Instead he epitomizes the new type of threat that Indonesia is facing with JI’s formal structure and networks dismantled. Lawanga’s bomb-making skills and connections to jihadis in Java enable him to operate small, hard-to-detect, and mobile cells independent from centralized, top-down leadership.

As Densus 88 hones in on terrorist leaders, infiltrates their networks, and makes it more difficult for jihadis coming from abroad to continue their operations in Indonesia, terrorists with Lawanga’s skill-set and capabilities will likely become scarce. Furthermore, teaching the next generation of Indonesian jihadis bomb-making skills in the same way that Lawanga learned from Azahiri Husin will become more difficult as Densus 88 kills off or arrests the older generation of jihadis. Crack downs on havens like the former Tanah Runtuh community will also disperse these jihadis further afield accelerating decentralization of terrorist networks in Indonesia.

Staying on the run and leading small cells in Java will not be easy for Lawanga. The Densus 88 of today has been professionalized to a degree in stark comparison to 2006 when it managed to let Lawanga escape capture. The July 19 operation that netted a dozen suspects in Lawanga’s network will provide Densus 88 with intelligence from those suspects’ interrogations. The answers Indonesian authorities receive from these questionings may offer them leads on Lawanga’s whereabouts and activities. Densus 88 has been focused sharply on terrorists in Java increasingly since November 2005 (see Terrorism Monitor, August 12, 2011) when it eliminated Lawanga’s teacher, Azahari Husin. It is hard to imagine that today’s Densus 88 will spare Lawanga any luck the next time it senses his presence.

Notes

1. His last name is often misspelled as “Bulaga” in Indonesian and foreign media, but Buraga is the correct spelling.

2. Pancasila encompasses the five principles upon which Suharto governed Indonesia, but that JI and its affiliates in Indonesia, including the Poso jihadis, wanted to overturn in order to create a state governed by Islamic principles. The five principles of Pancasila are: Belief in the one and only God; Just and civilized humanity; The unity of Indonesia; Democracy guided by the inner wisdom in the unanimity arising out of deliberations amongst representatives; and Social justice for the all of the people of Indonesia.