China’s UPR: Support for Abuse Stalls at the UN

China’s UPR: Support for Abuse Stalls at the UN

Executive Summary:

- Analysis of UPR data suggests the PRC’s influence at the UN, at least on human rights issues, may be plateauing.

- The UPR outcomes reflect a potentially shifting global consensus on the country’s human rights practices, with increased coordination among critics and less cohesive support from friendly States. This suggests opportunities for more robust international advocacy for human rights improvements within the PRC.

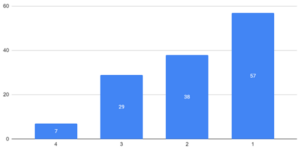

- The fourth UPR of witnessed a significant rise in the number of UN Member States submitting Advance Questions, from nine in 2009 to 36 in 2024, indicating heightened global scrutiny of the PRC’s human rights record, especially concerning international legal obligations, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong.

- The range of Recommendations made during the UPR session suggests a complex mix of support and criticism. The PRC exhibited considerable influence, persuading many member states to praise its record on human rights.

This is the second part of a two-part article examining the influence of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) at the United Nations through the lens of the Universal Periodic Review of its human rights. The first part, China’s Universal Periodic Review Tracks Its Influence At The UN, was published in Volume 24, Issue 2 of China Brief on January 19, 2024. For an explanation of the UPR process, please refer to this previous article.

The fourth round of the United Nations’ Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) took place on Tuesday, January 23 (United Nations, January 23). The first three UPRs, which took place in 2009, 2013, and 2018, occurred simultaneously with the PRC’s growing stature and influence at the UN. Consequently, these three UPRs saw an increase in questions from PRC-friendly states that were approving of the PRC’s human rights record and an attendant dilution of critical comments (China Brief, January 19). Looking at the trends between China and the other UN Member States at this review can serve as a litmus test to measure its relationships with the international community today.

Two features of the UPR that this article addresses are the Advance Questions—which are submitted in writing before the UPR session takes place—and the Recommendations that are made in the approximately one-minute-long time slot that is allotted to each UN Member State during the three-hour UPR session itself.

Trends in Advance Questions

Between 2009 and 2024, the number of UN Member States who submitted Advance Questions to China’s UPR increased dramatically, from nine to 36. This figure is inclusive of both questions that endorse the PRC’s human rights record and those that are critical of it. Among the latter, the most frequently raised topic is its compliance with international human rights law. This makes sense, given that the UPR’s original mandate is to review member states’ compliance with international legal obligations.

There has been a marked increase in the number of Advance Questions that address human rights violations in the PRC’s peripheral Autonomous Regions of Xinjiang and Tibet, as well as in the Special Administrative Region (SAR) of Hong Kong. These have reflected the deterioration in human rights in these regions across the last fifteen years. Part of the increased prominence of these issues at the UN can also be attributed to an increase in international awareness and the success of civil society and advocacy groups in focusing attention on the severity of the situations. Meanwhile, new themes have emerged across the UPRs, such as an increasing number of questions regarding the rights of LGBT+ people in the PRC.

States that are friendly to the PRC, meanwhile, have increased the number of questions that they have submitted over the years, but few have addressed compliance with international law. These questions typically concern development, poverty alleviation, and the environment—important issues that have an impact on people’s human rights, but also the rights that Beijing is most enthusiastic about promoting at home and abroad. This is in contrast to the indivisible and individual conception of human rights as understood in western discourse. Framing questions with the PRC’s preferred focus in mind allows States to avoid criticizing the PRC while permitting it to burnish its credentials as a proponent of a certain kind of human rights. Indeed, questions from friendly States are typically congratulatory and are not necessarily couched in such a way that answers are required.

To provide one example, Cuba’s Advanced Questions submitted prior to this month’s session included the following: “As it is pointed out in the Report to the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, China is advancing the Healthy China Initiative. Could you please share some good practices?” Not only is this a compliment which circumscribes the PRC’s responses, allowing it to avoid engaging with its extremely poor human rights violations, but this type of question dilutes the discourse and erodes the seriousness of the debate. At a superficial level, the appearance of both compliments and criticisms illustrates a rather balanced picture of a country’s human rights. However, this is far from the truth. Rather, the PRC coordinates with friendly states to pose such questions in order to create an overall picture which is at the very least equivocal about its human rights posture. By engineering an influx of approbatory comments at the UN, the PRC can subsequently brush off real criticisms when they arise by pointing to these alternative, more conciliatory characterizations. This behind-the-scenes management by the PRC is also why many of the questions from its friends appear repetitive. The homogeneity of much of the language is suggestive of States merely copying and pasting PRC talking points, perhaps received in briefings from the Chinese Mission. Evidence of such tactics goes back several decades. According to one scholarly account, in 1990 an African diplomat at the UN in Geneva was “visited by ten Chinese officials in his hotel room who explained to him how best to vote and what the economic consequences would be for his country if he rejected the Chinese script.” [1]

Trends in Recommendations

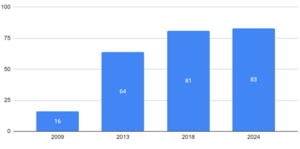

States have the opportunity to provide the PRC with Recommendations, which should ideally consist of constructive suggestions for improving human rights policies and practices. Part 1 of this article analyzed the number of UN Member States that made Recommendations to China beginning with the word “continue.” This analysis is extended here to include the updated data from this month’s UPR (Table 2).

These “continue” Recommendations are a rough proxy for States’ attitudes towards the PRC. They provide a fairly good litmus test which allows for straightforward comparisons across all participating States. However, such an analysis does not allow for a more granular approach of qualitatively assessing the substance of individual States’ Recommendations, or indeed of the Recommendations themselves. However, this methodology functions as a reasonable proxy, as Recommendations that urge a state to “continue” doing something implies that that State is already on the right track and need not change its current policy trajectory. Given that it is unlikely a State would request that the PRC continue with any of its practices that clearly contravene its international human rights obligations, such Recommendations are indicative of those States’ positive relationships with the PRC.

Over time, the number of UN Member States that have made such Recommendations has varied. The earlier UPRs saw a sharp increase. However, there has been very little change between the third and fourth UPRs. At one level, this—as well as the number of Advance Questions submitted—reflects a general increase in interest and engagement in the UN UPR across UN Member States. But it also reflects how Bejing was able to rally significant support and rapidly forge new friendships between 2009 and 2018. The lack of meaningful change between 2018 and 2024 suggests that the PRC may have reached an upper limit with its powers of persuasion for now. Whilst they have gained new friends, they have also lost some supporters.

For example, this year the State of Palestine gave China three very encouraging recommendations: “Continue its efforts in taking measures to improve health care services to guarantee the right to good quality and affordable health care to all persons including marginalized individuals; Continue its efforts to ensure equal access to education in urban and rural areas; Continue participation in the global human international rights governance system and strengthen mutual learning on human rights views and practices.” Supportive comments like these could be offered in the hope of receiving Chinese support in Palestine’s current conflict with Israel—it had not previously made any Recommendations to China (United Nations, January 23).

On the other hand, New Zealand had previously made Recommendations beginning with the word “continue” that urged the PRC to improve its human rights record in an encouraging way. This year, their cautious optimism ended. Instead, they made firm and direct Recommendations addressing civil and political rights, women’s rights, and specifically highlighting violations against Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Hong Kongers (United Nations, January 23).

Deceleration in the growth of the PRC’s international supporters correlates with observable trends outside of the UN. Many States began the 2010s enthusiastic about the PRC and eager to deepen engagement and reap the benefits from a more integrated and emerging global superpower. This was initially enhanced by the touted benefits of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other collaborative projects. However, perceptions in many parts of the world have shifted more recently, as excesses and implementation issues within the BRI have forced Beijing to distance itself from certain aspects of the project, and reorient BRI’s strategic direction This has damaged the friendships and led to less enthusiastic support for the PRC in international fora (CFR, April 6, 2023). These trends are reflected at the UPR. An analysis reveals a correlation between BRI signatories who receive higher levels of Chinese investment and those who offer positive Recommendations at the UPR. Inversely, States that were not a part of BRI were much less likely to give a supportive or even neutral Recommendations at the UPR (China Digital Times, January 26). Furthermore, many of the Recommendations made by friendly States did not use all the time allocated and spent much of it on formalities. Many of the Recommendations were vague and insubstantial—even States who feel the need to performatively support the PRC seem to have difficulty praising its approach to human rights in the last five years.

Across the four UPR cycles to date, only seven States have made “continue” Recommendations in every session: Bhutan, Egypt, Mozambique, the Russian Federation, Viet Nam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. As human rights have regressed under Xi Jinping, with several parliaments and governments recognizing an ongoing genocide in Xinjiang, the bar for human rights condemnations at the UN UPR has been raised (US Department of State, January 19, 2021; BBC, February 23, 2021; France 24, January 20, 2021; Reuters, February 25, 2021). Notably, 57 UN Member States made Recommendations beginning with “Continue” just once. This speaks to an inconsistency in the level of PRC support at the UN, suggesting that there are few States who are truly committed to backing the PRC over the long-term and that most States view their relationship as transactional.

Beijing’s most vocal critics have evolved over the last fifteen years. An increasing ability to coordinate has led to strong unified messages on specific issues being sent. [2] For example, in 2024, 18 UN Member States made Recommendations about the human rights violations in Hong Kong (Hong Kong Watch, January 23). This was a 300 percent rise from the six such mentions from 2018 (Hong Kong Watch, November 29, 2023). This rise stems both from enhanced coordination and in response to the deterioration in human rights in Hong Kong following the proposal of the National Security Law in 2019—a trend that is also visible among Uyghur, Tibetan, and other groups whose human rights are also a subject of the PRC’s UPR (see for example, Central Tibetan Administration, January 24; ChinaFile, January 22).

Conclusion

The conclusion of the UN’s Universal Periodic Review of human rights within the PRC last week has provided the most current data to track the country’s relations with other UN Member States. The picture that emerges from aggregating across fifteen years’ worth of data supports the argument that beyond a small core of loyal cheerleaders for the Chinese regime, many of the States that act in the PRC’s favor are fair-weather friends only, operating with a transactional calculus. Meanwhile, the PRC’s most vocal critics are increasingly coordinated in their condemnation of human rights abuses.

There is thus a growing consensus regarding the PRC’s human rights violations, and an acknowledgement that they have worsened since 2009. Firmer, more coordinated condemnation could persuade other States to criticize the PRC, and lead to foreign policies that have to acknowledge violations in States’ dealings with the country. In contrast, Recommendations from the PRC’s friends were less coordinated and more nebulous than in the past. This suggests Beijing’s goals for global influence may not rest on as solid a foundation as one might expect. This could mean that there are more opportunities for Beijing’s critics to rally the middle ground, where States are now more likely to be neutral than supportive of the PRC, and increase pressure to blunt the sharper repressive instincts of the regime. This month’s UPR suggests that China’s rise is slowing down and that there is cause for optimism for the promotion of human rights. This can be achieved through the United States and its allies promptly working with “middle ground” countries to consolidate an alliance to criticize the PRC’s abysmal human rights record. This would also help prevent future violations, name and shame, and seek pathways for accountability. This should also be a key component in shaping the United States’ and its allies’ policies towards the PRC more broadly.

Notes

[1] Rosemary Foot and Rana Siu Inboden, “China’s Influence on Asian states during the creation of the UN human rights council: 2005-2007” in E. Goh, ed., Rising China’s Influence in Developing Asia (OUP 2016).

[2] Evidence of coordination has been highlighted in the author’s conversations with diplomats.

Appendix

Table 1: Trends in Advanced Questions

| Advanced Questions | ||||||

| Compliance with international law | Hong Kong | Tibet | Xinjiang | Death Penalty | Freedom of expression | |

| 2009 | ||||||

| Canada | x | |||||

| Czech Republic | x | x | ||||

| Denmark | x | x | ||||

| Latvia | x | |||||

| Liechtenstein | x | |||||

| Netherlands | x | |||||

| Norway | x | x | x | x | ||

| Sweden | x | x | x | x | ||

| UK | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 2013 | ||||||

| Australia | x | |||||

| Bangladesh | ||||||

| Belgium | x | x | ||||

| Canada | x | x | x | x | ||

| Cuba* | ||||||

| Czech Republic | x | x | ||||

| Myanmar | x | |||||

| Spain | ||||||

| 2018 | ||||||

| Australia | x | x | ||||

| Austria | x | x | x | |||

| Belgium | x | x | x | |||

| Bolivia* | x | x | ||||

| Cambodia* | x | |||||

| Canada | ||||||

| Cuba* | x | |||||

| Germany | x | x | x | x | ||

| Laos* | x | |||||

| Nepal* | x | |||||

| Netherlands | x | x | x | |||

| Norway | x | x | x | x | ||

| Pakistan* | x | |||||

| Philippines | x | |||||

| Portugal** | x | |||||

| Slovenia | x | |||||

| Spain | x | |||||

| Sweden | x | x | x | x | ||

| Switzerland | x | x | ||||

| UK | x | x | x | |||

| Uruguay | ||||||

| US | x | x | x | x | ||

| Venezuela* | x | |||||

| Viet Nam* | x | |||||

| Australia | x | x | ||||

| 2024 | ||||||

| Algeria* | x | |||||

| Antigua and Barbuda* | x | |||||

| Australia | x | x | ||||

| Austria | x | x | ||||

| Bangladesh* | ||||||

| Belarus* | ||||||

| Belgium | x | x | x | |||

| Bolivia* | ||||||

| Burundi* | ||||||

| Cameroon | x | |||||

| Canada | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Cuba* | x | |||||

| DPRK | x | |||||

| Eritrea | x | |||||

| Germany | x | x | x | x | ||

| Iran* | ||||||

| Laos* | ||||||

| Liechtenstein | x | x | x | x | ||

| Netherlands | x | x | x | x | ||

| Nicaragua* | ||||||

| Pakistan* | ||||||

| Portugal** | x | |||||

| Korea | ||||||

| Russia* | x | |||||

| Singapore* | ||||||

| Slovenia | ||||||

| Spain | x | x | ||||

| Sri Lanka* | ||||||

| Sweden | x | x | x | |||

| Switzerland | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Syria* | ||||||

| UK | x | x | x | x | x | |

| US | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Venezuela* | x | |||||

| Viet Nam | x | |||||

| Zimbabwe | ||||||

*Indicates that the question the country asked was a ‘positive’ one, which praised the PRC’s human rights record

**On behalf of the Group of Friends on NMIRF’s (‘national mechanism for implementation, reporting and follow-up’)

(Source: author’s own, data from United Nations, undated)

Table 2: Which States made Recommendations that began with the word “Continue”?

| 2009 | 2013 | 2018 | 2024 | |

| State | ||||

| Afghanistan | x | |||

| Algeria | x | x | x | |

| Angola | x | x | ||

| Argentina | x | x | ||

| Azerbaijan | x | x | x | |

| Bahrain | x | x | x | |

| Bangladesh | x | x | x | |

| Barbados | x | |||

| Belarus | x | x | x | |

| Belgium | x | |||

| Benin | x | |||

| Bhutan | x | x | x | x |

| Bolivia | x | x | ||

| Botswana | x | |||

| Brazil | x | |||

| Brunei Darussalam | x | x | x | |

| Bulgaria | x | |||

| Burkina Faso | x | |||

| Burundi | x | |||

| Cabo Verde | x | |||

| Cambodia | x | x | x | |

| Cameroon | x | x | ||

| Central African Republic | x | |||

| Chad | x | |||

| Chile | x | x | ||

| Colombia | x | |||

| Congo | x | x | ||

| Cuba | x | x | ||

| Cyprus | x | |||

| Djibouti | x | x | x | |

| Dominica | x | |||

| Dominican Republic | x | x | ||

| DPRK | x | x | ||

| DR Congo | x | |||

| Ecuador | x | |||

| Egypt | x | x | x | x |

| El Salvador | x | |||

| Equatorial Guinea | x | x | ||

| Eritrea | x | x | x | |

| Ethiopia | x | x | x | |

| Fiji | x | x | ||

| Gabon | x | x | x | |

| Gambia | x | |||

| Georgia | x | |||

| Germany | x | |||

| Ghana | x | x | ||

| Greece | x | |||

| Guatemala | x | |||

| Guinea | x | |||

| Guyana | x | |||

| Hungary | x | x | x | |

| Iceland | x | |||

| India | x | x | x | |

| Indonesia | x | x | x | |

| Iran | x | x | x | |

| Iraq | x | |||

| Jordan | x | x | x | |

| Kazakhstan | x | |||

| Kenya | x | x | x | |

| Kuwait | x | x | ||

| Kyrgyzstan | x | x | x | |

| Laos | x | x | ||

| Latvia | x | x | ||

| Lebanon | x | x | ||

| Lesotho | x | x | ||

| Libya | x | |||

| Madagascar | x | |||

| Malawi | x | |||

| Malaysia | x | x | x | |

| Maldives | x | |||

| Mali | x | x | ||

| Malta | x | |||

| Mauritania | x | |||

| Mauritius | x | x | ||

| Moldova | x | |||

| Mongolia | x | x | ||

| Morocco | x | x | x | |

| Mozambique | x | x | x | x |

| Myanmar | x | x | ||

| Namibia | x | x | ||

| Nepal | x | x | x | |

| New Zealand | x | x | ||

| Nicaragua | x | x | ||

| Niger | x | x | ||

| Nigeria | x | x | ||

| Oman | x | |||

| Pakistan | x | x | x | |

| Panama | x | |||

| Peru | x | x | ||

| Philippines | x | x | ||

| Portugal | x | |||

| Qatar | x | x | x | |

| Republic of Korea | x | x | ||

| Romania | x | |||

| Russian Federation | x | x | x | x |

| Rwanda | x | |||

| Samoa | x | |||

| Saudi Arabia | x | x | ||

| Senegal | x | x | ||

| Serbia | x | x | x | |

| Seychelles | x | |||

| Sierra Leone | x | |||

| Singapore | x | x | x | |

| Somalia | x | |||

| South Africa | x | |||

| South Sudan | x | |||

| Sri Lanka | x | x | ||

| State of Palestine | x | |||

| Sudan | x | |||

| Syrian Arab Republic | x | x | x | |

| Tajikistan | x | x | ||

| Tanzania | x | |||

| Thailand | x | x | ||

| Timor-Leste | x | |||

| Togo | x | x | ||

| Trinidad and Tobago | x | |||

| Tunisia | x | x | ||

| Türkiye | x | |||

| Turkmenistan | x | x | ||

| UAE | x | x | x | |

| Uganda | x | x | ||

| Ukraine | x | |||

| Uruguay | x | |||

| Uzbekistan | x | |||

| Venezuela | x | x | x | |

| Viet Nam | x | x | x | x |

| Yemen | x | x | x | x |

| Zambia | x | |||

| Zimbabwe | x | x | x | x |

| Total | 16 | 64 | 81 | 83 |

Source: author’s own, data from United Nations, undated.

Number of UN Member States that made Recommendations beginning with “Continue”

Number of times States made Recommendations beginning with “Continue” across all four UPRs