Hot Issue: The Battle for Southern Yemen

Hot Issue: The Battle for Southern Yemen

Executive Summary

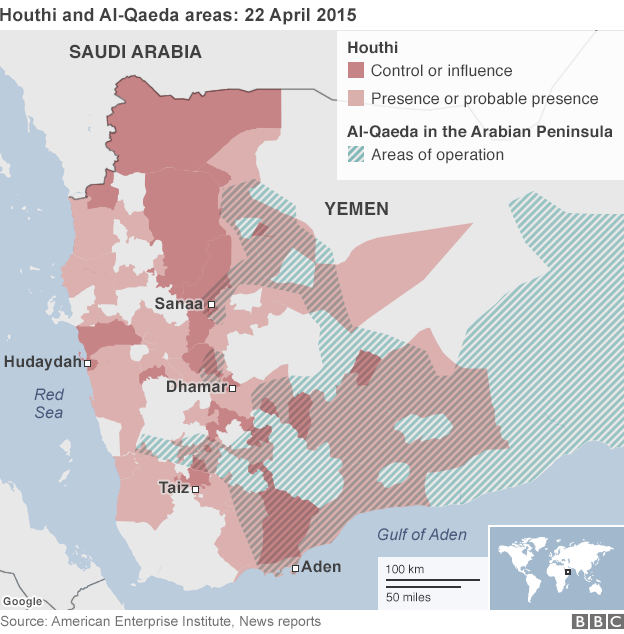

On March 25, Saudi Arabia and its coalition partners launched air strikes and implemented a naval blockade against Yemen to weaken Yemen’s Zaydi Shi’a Houthis and to reinstall the exiled government of Yemeni President Abd Rabbu Mansur al-Hadi. Operation Decisive Storm has now lasted ten weeks and has failed to achieve either of these goals; however, it has ignited a civil war in Yemen that has little to do with sectarian divisions and everything to do with north-south tensions. In addition to rekindling old fights, the Saudi-led campaign, which has destroyed much of Yemen’s infrastructure and produced a nationwide humanitarian crisis, has also created the ideal conditions for the expansion of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and now, the Islamic State.

Introduction

Ten weeks of air strikes by Saudi Arabia and its partners have failed to substantively weaken Yemen’s Houthis. The capital of Sana’a, most of northwest Yemen and parts of the southern port city of Aden remain in the control of the Houthis, a northern Yemeni rebel group, and their allies. While the Saudi-led war has thus far failed to force the Houthis to retreat, it has ignited a long smoldering conflict between forces in north and south Yemen. Although much of the media coverage of the fighting in Yemen has characterized it as a battle between Sunnis and the Zaydi Shi’a Houthi rebels, the truth is far more complex. The battle for south Yemen has little to do with sectarian differences and everything to do with a failed unification and dwindling resources. The war between the Houthis and their allies and south Yemen’s militias and People’s Committees will have no victors—beyond takfiri groups like al-Qaeda—and could result in the long-term fragmentation of Yemen.

A Divided Country

Few times in Yemen’s history have existed when the country has been united under one ruler or regime. Yemen’s mountainous topography, its deserts and, most importantly, its cultural traditions have long worked against the construction of a strong centralized state. In both the north and the south, the coercive authority of the state is limited, and power is diffuse. Power is most often divided among—and contested by—numerous tribal blocs, influential families and formal and informal functionaries of the state. While there is a “Yemeni” identity that encompasses all of Yemen, north and south Yemen are politically and socio-culturally distinct and have two very different modern histories.

What can be broadly termed north Yemen—those parts of northwest Yemen that made up the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR)—has traditionally been dominated by two tribal confederations, the Hashid and the Bakil. The two confederations of tribes are made up of numerous tribes and clans whose members are both Zaydi Shi’a and Sunni. [1] For much of its history, north Yemen was ruled by a Zaydi imam, whose rule was, to varying degrees, dependent on the cooperation and acquiescence of north Yemen’s most powerful tribes. The 1962-1970 North Yemen Civil War, in which republican forces fought royalist forces that supported the imamate, led to the dissolution of the imamate and the marginalization of Zaydism and members of the Zaydi elite. This marginalization led directly to the rise of what became known as the Houthi Movement, which was dedicated—at least in its early years—to peacefully preserving and protecting Zaydi traditions and beliefs.

South Yemen’s history, partly due to its long coastline and the ancient and strategic port of Aden, was very different from its northern neighbor. In 1839, the British established an outpost in Aden, which became a Crown Colony in 1937. For much of their time in south Yemen, the British pursued a policy of limited and strategic engagement with the rulers of south Yemen’s autonomous sultanates that stretched from Lahij, near Aden, to the Hadramawt in the east. As the importance of Aden grew and as the expansionist aims of north Yemen’s ruler, Imam Yahya (1869-1948), became clearer, British authorities created what came to be known as the Eastern and Western Protectorates. The protectorates were a loose confederation made up of the tribal shaykhs and sultans that governed the territories surrounding Aden. It was not until 1963, when it faced a rising tide of nationalist sentiment in south Yemen, that the British attempted to establish a more formal state structure in the form of the Federation of South Arabia.

The nationalists in south Yemen then launched a deadly insurgency against the British that lasted until 1967 when the British hastily departed, and an independent south Yemen was formed. The nascent south Yemen, which was named the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) in 1969, was dominated by the Marxist National Liberation Front (NLF). The leadership of the NLF launched an ambitious and partly successful program to remake south Yemen into a Marxist state. Tribalism and tribal identities were suppressed, and some cultural values were altered. Veiling of women declined, schools were made coeducational, and in marked contrast to the north, a relatively transparent system of bureaucratic institutions replaced the authority of ruling families, shaykhs and tribal elders. [2]

A Failed Unification

With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, the PDRY lost its primary source of foreign aid. The already weak economy of the PDRY was in danger of collapsing. The rapidly deteriorating economy in the south and the erroneous belief by the leadership of the PDRY that they could dominate the government of the far more populous Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) led to a hasty and ill-planned unification of north and south Yemen in 1990. Early on, the unification was marred by assassinations of politicians from the now former PDRY. The Yemen Socialist Party, which represented much of the south, did poorly in the national elections held in 1993. As a result, the framework for unification broke down, and, in 1994, the south declared that it was seceding from the union and became the short lived Democratic Republic of Yemen (DRY).

The 1994 civil war between the government led by Ali Abdullah Saleh, which was dominated by northerners, and the government of the rebellious south set the tone for north-south relations for much of the next two decades. The rebellion in the south was quickly put down by the militarily superior forces of the north, which relied heavily on tribal militias. Punitive measures followed the rebellion. Many of south Yemen’s relatively well-trained bureaucrats and military officers were fired, and influential northerners who supported Saleh and his war in the north seized properties, businesses and land across south Yemen. Many southerners viewed this as little different from government sanctioned looting. The unequal distribution of revenue from the development of Yemen’s oil and gas resources, the bulk of which are located in what was the PDRY, led to more condemnations of the north’s dominance over the south. The brief but dramatic increase in state revenues that arose from Yemen’s oil resources primarily benefited the north; south Yemen remained economically and culturally marginalized.

Beginning in the early 2000s, south Yemen’s forcibly retired military officer and bureaucrats began organizing a peaceful resistance movement that sought redress of many of the injustices that arose from the 1994 civil war. The movement, known as the Southern Movement, was, for most of its early history, amorphous and consisted of numerous groups, often with very different agendas. As the Yemeni economy declined along with falling oil production, the resistance movements in the south gained influence and their calls for secession became more strident. The Yemeni government, still led by Saleh, launched what were most often punitive and violent crackdowns on members of the various southern separatist groups. The leadership and membership of these separatist groups now make up the majority of the leadership and membership of the People’s Committees that are fighting to control the south.

During the popular uprising against the Saleh government in 2011, the southern separatists groups, in particular the Southern Movement, gained more ground. Much of south Yemen was left ungoverned as military units and government officials aligned with Saleh and/or the north withdrew. Both southern separatists and takfiri groups like al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) filled the vacuum.

The installation of Abd Rabbu Mansur al-Hadi a southerner, as president in 2012, did little to quell secessionist ambitions in the south. Hadi, who had sided with Saleh and the north in the 1994 civil war, failed to address the southerners’ grievances, and the security services continued to pursue and arrest members of southern secessionist organizations during Hadi’s tenure.

Houthis on the Offensive

At the same time that southern separatists were making gains in the south, the Houthis were consolidating their hold on a large swath of northwest Yemen. As in the south, what remained of the Yemeni military either defected or fled the northern governorates of Sa’ada and Hajjah following the popular uprisings of 2011. The Houthis, who prior to 2011 had controlled Sa’ada and large portions of Hajjah, rapidly expanded by means of alliances and military force into the governorates of al-Jawf and Amran. The Houthis’ gains in northwest Yemen culminated in their September 2014 takeover of Sana’a (al-Jazeera, September 27, 2014). The march into the capital by Houthi forces and their allies was largely uncontested due to the fact that most of the Yemeni Armed Forces stationed in and around Sana’a stood down. The commanders of most of the military forces located near the city were either loyal to former president Saleh, who is now nominally allied with the Houthis, or they were opposed to President Hadi and his government (Al-Monitor, September 29, 2014).

Even after the Houthi takeover of Sana’a, the Houthi leadership, led by Abdul Malik al-Houthi, remained engaged with—and on relatively good terms with—much of the leadership of the various southern separatist groups. In what was no doubt an attempt to broaden the appeal of the Houthis as a national movement, Houthi rhetoric identified with the southerners as a fellow oppressed group.

After their seizure of Sana’a, the Houthis steadily increased the pressure on President Hadi and his government. The Houthis set up what was essentially a shadow government that, in the beginning, seemed to be motivated by a genuine desire to crack down on what was rampant and long-standing corruption within the Yemeni government (London Review of Books, May 21). The Houthis’ plan to remain a shadow government was upended, however, when President Hadi abruptly resigned on January 22 (al-Arabiya, January 22). The Houthis were unprepared and lacked the support to officially take power in Sana’a as they knew that that they did not have enough support to lead a government. Consequently, the leadership insisted on continuing negotiations with all stakeholders in Yemen, including representatives from the south.

On February 21, President Hadi fled Sana’a for Aden, where he repudiated his resignation (The National [Abu Dhabi], February 21). Hadi’s attempt to set up an alternative capital in Aden prompted the Houthis and their allies to push south. In response to the military gains made by the Houthis, who were on the outskirts of Aden by March 25, Hadi left for exile in Riyadh (al-Jazeera, March 25). Saudi Arabia and its allies launched Operation Decisive Storm on March 25, the same day that Hadi fled Aden.

Battle for the South

According to the former UN Special Adviser on Yemen, Jamal Benomar, negotiations between all major stakeholders in Yemen were nearing an interim conclusion on a power sharing agreement when Saudi Arabia and its allies launched Operation Decisive Storm on March 25 (Wall Street Journal, April 26). Despite the Houthis’ push into south Yemen, representatives from the south remained engaged in negotiations. The commencement of aerial strikes by Saudi Arabia and its partners ended the negotiations and led to a dramatic escalation of violence between the Houthis and southern militias, who, with the support of Saudi Arabia, were determined to reverse the gains made in the south by the Houthis and their allies. At the same time, the Houthis, now assisted by a significant percentage of the Yemeni Armed Forces, redoubled their efforts to take and hold as much territory in the south as possible in order to prevent Saudi Arabia and its partners from creating a beachhead, from which they could more easily reinstall and support the government of President Hadi.

The seizure of the southern port of Aden was critical to both sides. As the former capital of an independent south Yemen, Aden is strategically and psychologically important for southern separatists. At the same time, as a gateway to Yemen, the Houthis and their allies must prevent the port from being controlled by southern militias. As a result, Aden has seen some of the heaviest and most brutal fighting in what has been ten weeks of war. While Saudi Arabia has air-dropped weapons to southern separatist forces and has provided them with aerial support, much of the city remains in the hands of the Houthis and their allies. The aerial bombardment and Houthi aligned forces’ indiscriminate use of artillery in densely populated urban areas has laid waste to much of what was already one of Yemen’s most impoverished cities.

The stalemate in Aden mirrors the tactical situation across much of south Yemen. Neither Houthi aligned forces nor the militias of the People’s Committees, even with Saudi support, are strong enough to defeat the other.

A War in Which the Only Victors are AQAP and the Islamic State

After ten weeks of bombing that have resulted in 2000 deaths, over half of which are civilian casualties, and billions of dollars in damage to infrastructure and private property, the Saudi-led war has achieved little beyond igniting a civil war that neither side can win, regardless of the backing they receive from outside powers (United Nations, May 18; Voice of America, May 22). The divisions between north and south Yemen run deep, but the two regions are inextricably linked. A divided Yemen is no more economically viable than it was in 1990 when the dire economic situation in what was an independent south Yemen drove the two countries to unite. Since 1990, Yemen’s population has increased dramatically, its water and oil resources have diminished significantly and now, especially following the most destructive war in its history, the country is far poorer.

The Saudi-led war and its naval blockade of Yemen’s ports have already resulted in what is Yemen’s most serious, and first, nationwide humanitarian crisis. More than 60 percent of Yemenis are now in need of humanitarian assistance, and there are 545,000 internally displaced persons (United Nations, May 18). Yemen’s already limited state services have collapsed. The war has produced the conditions in which groups like AQAP and the Islamic State thrive.

A protracted war in Yemen will have no victors or beneficiaries beyond takfiri groups like AQAP and now the Islamic State, which had little or no presence in Yemen before March. Both jihadist organizations are taking advantage of the power vacuum left in the wake of the Saudi-led war in Yemen. The Houthis, who are sworn enemies of al-Qaeda and all takfiri groups, had been on the offensive against AQAP. Before the start of Operation Decisive Storm, the Houthis and elements of the Yemeni Army had largely pushed AQAP out of at least two Yemeni governorates, including al-Bayda, which had been an AQAP stronghold. Now that the Houthis are battling with forces in the south, the pressure on AQAP has largely been removed. Concurrent with curtailment of Houthi led operations against AQAP, the military capabilities of the Yemeni Armed Forces have been seriously diminished. Saudi-led air strikes have largely destroyed the Yemeni Air Force, which was critical to the government’s ability to fight AQAP. The air strikes have also weakened the well-equipped and well-trained Republican Guard, which remains loyal to Saleh, who is allied with the Houthis.

AQAP quickly took advantage of the power vacuum by freeing its operatives from prisons across Yemen and going on the offensive (Telegraph, April 2). Al-Mukalla, Yemen’s fifth largest city, is now controlled by AQAP as is much of the governorate of Hadramawt, which produces a significant percentage of Yemen’s oil and gas (Yemen Times, April 6). The Islamic State has also seized the opportunity to insert itself into Yemen. The jihadist group has released a video showing its members executing Yemeni soldiers in the governorate of Shabwa (al-Bawaba, April 30).

With the Yemeni Army divided and degraded and with the Houthis battling to maintain a strategic foothold in Aden and Taiz, AQAP and the Islamic State are free to expand and consolidate their control of large parts of eastern Yemen. If a negotiated settlement is not reached and if the Saudi-led war in Yemen persists, the recent gains by AQAP and the Islamic State will likely be just the beginning of a major expansion by both groups. An expansion that may well have serious repercussions for Yemen’s regional neighbors.

Conclusion

Operation Decisive Storm has failed to achieve its stated aims of reinstalling the exiled government of President Hadi or forcing the Houthis to retreat in Yemen. Even if the Saudi-led coalition launches a ground invasion, it is unlikely that these aims will be achieved. The campaign has also successfully ignited a long simmering civil war and created an ideal operational environment for AQAP and the Islamic State. If Saudi Arabia and its coalition partners persist in their efforts to forcibly reinstall Yemen’s exiled government and continue air strikes against the Houthis and their allies, the result may be the permanent fragmentation of Yemen along north-south boundaries.

The only way forward is—as was clearly recognized by the Houthis, representatives of the south and most stakeholders before the start of Operation Decisive Storm—is through a negotiated settlement that recognizes Yemen’s long history of dispersed authority. Both the Houthis and members of south Yemen’s numerous separatist movements have long called for a political and constitutional framework that leads to the installation of a federal government in Sana’a that allows for strong regional governance and the equal distribution of resources.

Michael Horton is an analyst whose work primarily focuses on Yemen and the Horn of Africa.

Notes

1. It should be noted that while Zaydism is technically a sect within the Shi’a branch of Islam, it is doctrinally closer to Sunni Islam and is frequently referred to as the fifth school of Sunni Islamic thought.

2. See Noel Brehony’s Yemen Divided: The Story of a Failed State in South Arabia for an in-depth history of the PDRY.