Making Sense of China’s Caribbean Policy

Making Sense of China’s Caribbean Policy

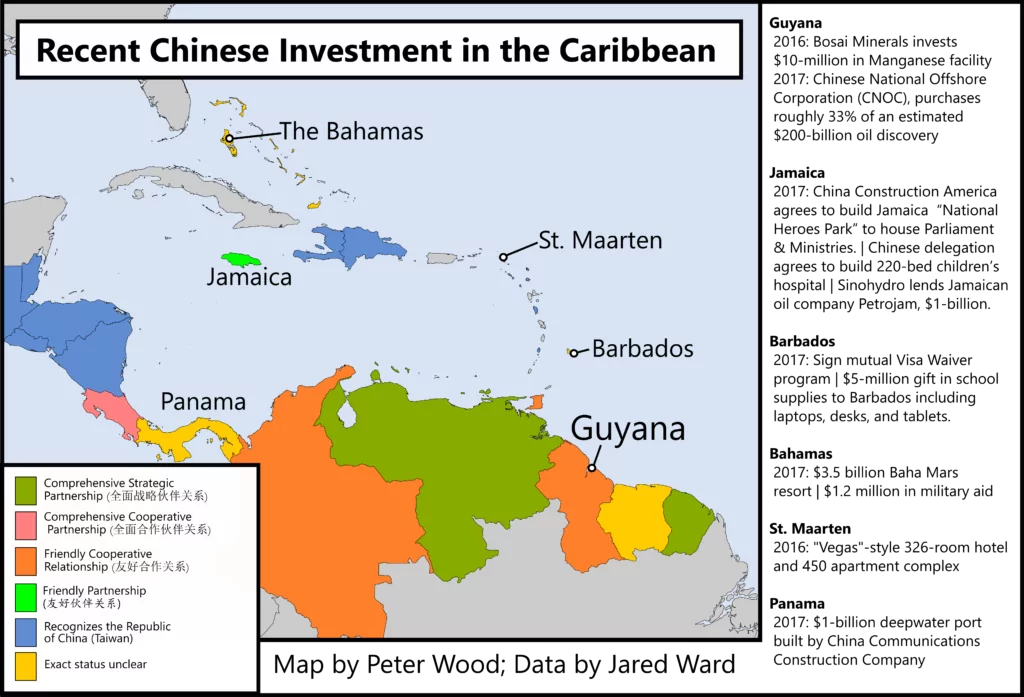

While the world’s attention focuses on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) connecting China with Eurasia and Africa, China is also making major investments in the Caribbean. In September 2016 the China Harbor Engineering Company (中国港湾工程有限责任公司) agreed to build a mega-port in Jamaica that would make the small island-nation a hub for mammoth Chinese ships soon crossing through an expanded Panama Canal (Jamaica Gleaner, September 24, 2016). Valued at $1.5 billion, the port will become China’s largest in a region that has become a growing target for Chinese aid and diplomatic overtures. Barbados, a small island in the Lesser Antilles, has received millions from Chinese companies to restore historical landmarks and provide free medical care. In March of this year, a visa waiver program was created, aimed at opening the Caribbean paradise to an untapped market of 20-million Chinese tourists. Chinese funds have restored the Baha Mar luxury resort in the Bahamas. In Guyana, Chinese companies have developed the timber, oil, and gold industries.

China’s short and long-term interests in the region appear to be not only motivated by economics but also aimed at connecting nations in America’s backyard to a Maritime Silk Road under Chinese influence. Recent developments in Sino-American relations have magnified the importance of border seas and the Caribbean, like the South China Sea, is likely to become a stage for clashing Chinese and American visions of global politics.

Chinese promises of aid to the Caribbean are consistent with a pattern elsewhere in the developing world. Beijing touts its own success as a developing nation; a rags to riches story of a non-Western power rising to global prominence. Caribbean officials generally view China’s checkbook diplomacy in a positive light. Generous loan terms and willingness to undertake badly needed infrastructure projects have helped offset drying up funds from Western institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. The influx of capital and projects bring promises of badly needed jobs for locals and training programs to teach transferable skills that last. However, on the ground, these promises are much more complicated, leaving locals wondering, as one Jamaican official did: “What does China want from us? That’s the big question that everyone has about this: Why?” (Global Post, April 22, 2011).

China’s Increased Caribbean Footprint

In late 2016, the PRC released its first White Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean, laying out guidelines for China’s engagement in the region (FMPRC, November 24, 2016). Xi Jinping’s 2014 visit to Trinidad and Tobago elevated interest in the region. The White Paper lays out broad principles such as noninterference in political affairs (不干涉内政的原则), mutually beneficial relationships (平等互利), and infrastructure and turnkey projects aimed at creating immediate improvements in the local economies. According to Beijing, this focus on addressing local problems is what makes their worldview different from America in the Caribbean. These lofty policy goals and carefully worded political statements are left to Chinese State Owned Enterprises (SOE) and lending banks to be put into practice.

China’s main arms in the Caribbean are a combination of lending banks, individual Chinese investors, and State Owned Enterprises. Chinese financial institutes such as the Chinese Export-Import Bank (中国进出口银行) make funds available to lend to SOE’s that bid on contracts to complete projects. The massive Baha Mar Bahama resort, valued at $2.4 billion, was built by the China Communications Construction Company (中国家桶建设股份在限公司). Chinese officials have also made clear that funds made available for nations involved in the BRI will also include Caribbean nations. Zhu Qingqao (祝青桥), head of the Latin American and Caribbean Affairs Department (拉丁美洲和加勒比司) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) made clear it clear that the Caribbean is part of Maritime Silk Road. In an interview in June with Cuban newspaper Granma, Zhu said that China put investments in Caribbean nations on par with projects receiving more focus in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East (Granma, June 2). Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness expressed his country’s interest in formally joining BRI; calling it a “noble expression,” that promoted cooperation and inclusiveness across the developing world (Jamaica Gleaner, June 22).

While China’s invitation for Caribbean nations to join BRI is tempting, Chinese SOE’s in the Caribbean have become embroiled in controversy and unveil a much more complicated reality where Chinese visions of development have mixed results and receptions. Accusations against Chinese companies range from flouting local labor laws to providing job and contracts exclusively to Chinese nationals, to an exploitation of natural resources (NACLA, June 26, 2013). This double-edged sword of Chinese aid to the Caribbean is on display in Guyana, China’s oldest CARICOM ally from the English-speaking Caribbean. Guyanese politicians continue to praise China as an invaluable partner and a potential model to follow to their own successful rise from poverty. In practice, Chinese promises of jobs, housing, and electricity have a mixed legacy that is often more gilded than gold.

Sino-Guyanese Relations: A Case Study in China’s Caribbean Policy

Guyana reluctantly embraces a paradox common to many developing states: rich in natural resources with poor economies. Besides its vast tracts of rain forest rich in lumber harvest, the discovery of an offshore oil and gas field earlier this year may make the small nation a major oil producer in the region (NYTimes, January 13). While China has shown a recent interest in these natural resources, Sino-Guyanese relations trace back to Guyana’s first Prime Minister Forbes Burnham. In 1972, Guyana went against Cold War currents and became the first former colony of former British West Indies to grant Beijing, not Taipei, diplomatic recognition. In the early years of the relationship, China would use Guyana as a laboratory of sorts and the site of its first foreign aid project in the Western Hemisphere—the Bel Lu Clay Brick Factory. The brick factory promised to make 10-million bricks a year; however, due to mismanagement and a lack of Chinese enthusiasm to step back in, the factory closed in the early 1990s and is now overgrown. Guyana has remained one of China’s most consistent CARICOM partners and in recent years has received millions in medical, military, and technical assistance. Other projects have improved telecommunications and built infrastructure aimed at making Guyana’s natural resources more accessible and further integrating its economy with its neighbors.

However, China has also been the target of criticisms common to its efforts elsewhere in the developing world. Local companies are often shut out of projects; all contracts are awarded to Chinese companies through a secretive bidding process. Furthermore, Chinese job creation promises often fall short and rely primarily on Chinese nationals. Baishanlin (白山林), a recent acquisition of Long Jian Forest Industries, a state-owned enterprise (SOE), has been at the center of a growing controversy and an example of how China’s development program can potentially sour bilateral relations.

Baishanlin arrived in Guyana over a decade ago and made promises familiar to many Caribbean nations. It would be given access to millions of acres of timber reserves in exchange for creating 10,000 local jobs and leaving behind a wood processing plant for the development of Guyana’s forest industry. Job creation has fallen short and those who do work for the SOE have filed grievances over inadequate pay, long hours, and exploitation of natural resources (Stabroek News, July 26, 2016). Additionally, Baishanlin’s promise to build a wood processing plant, a requirement for it to receive tax breaks has not been met, leading the Guyana Forest Commission to seize Chinese owned logging equipment and other assets (Demerara Waves, September 7, 2016). Most recently, the Chinese Development Bank has asked the Guyana government to hold off reallocating Baishanlin owned lands while it gathers the capital to recapitalize the loans owned by the company. (Demerarawaves, April, 19). As for now, the failed promises of Baishanlin remains a grim reminder for those in the region debating whether to widen their relations with Beijing.

Sympathetic Partner or Neo-Colonialist? Making Sense of China’s Caribbean Policy:

Guyana shows the double-edged sword of Chinese investment but also provides insights into China’s foreign policy toward the region as a whole. The entire Caribbean region has only 41-million people and there is little indication Chinese tourists are willing to make the around-the-world trip for vacation. What then is China’s interest in pouring billions of dollars into a region that can promise little in return? One possibility is that China’s policy is directed at Taiwan. The Caribbean is one of the last bastions for Taipei’s dwindling diplomatic alliances. The Dominican Republic, Belize, Haiti, Saint Lucia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Saint Vincent still recognize Taipei—not Beijing. This frames China’s checkbook diplomacy as a carrot to draw away Taiwan’s allies and isolate Taipei further politically. While the “One-China” policy does remain significant in all of China’s relations, this only explains a charm offensive toward nations like Panama, which until recently retained relations with Taiwan. China’s largest partners in the region—Jamaica, Guyana, Trinidad, and Barbados—have recognized Beijing exclusively since the 1970s.

China’s push for closer relations with these Caribbean nations was part of a pivot toward the ‘Third World’ in the waning years of the Mao Zedong Era (1949–1976). In the early 1970s, nations like Guyana and Jamaica became part of a Third World bloc that helped push the PRC’s final bid for UN membership. China’s initial interest in the Caribbean coincided with the beginning stages of Sino-American rapprochement when security anxieties about growing Sino-Soviet hostilities brought China from the recluses of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). The Caribbean became part a vast Third World that included Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America in which Mao envisioned China more fit to lead than the industrialized, white, Soviet Union or America. The Caribbean has always been unable to offer Beijing the same natural resources or strategic military alliances with countries in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. However, geopolitically the region provides economic and symbolic incentives for China’s investments. Many of China’s largest infrastructure projects, like ports in the Bahamas and Jamaica, will be used to accommodate larger volumes of cargo coming from China for transshipment throughout the Western Hemisphere. According to a proposal presented by Baishanlin, the driving force for the China National Development Bank Program’s investment in Guyana is its access to 277-million consumers, a $130-billion export market, and over $2-trillion in buying power. [2] Furthermore, in small Caribbean nations, China’s aid can make a greater impact for less investment; setting Beijing up to better compete with Western companies.

Conclusion

Beyond market access, China’s increased presence in Caribbean affairs can be understood as a subtle jab at American Western Hemisphere dominance at a time when Washington is pushing Beijing in the South China Sea. Xi Jinping, when he was still Vice President of China, visited Jamaica in 2009 and 2013 (Xinhua, February 14, 2009). Xi’s 2013 visit to Trinidad was one of his earliest trips abroad. In an interview before the trip Xi lauded Trinidad and China’s long cultural ties and common paths of development. In both 2009 as VP and later as President he described Sino-Caribbean relations according to an old Chinese saying which says “close friends stay close at heart though thousands of miles apart.” At a time when Washington is accusing China of bullying smaller countries in the South China Sea, Beijing has repeatedly held the Caribbean up as an of America’s history of big-power chauvinism. A Global Times editorial that lashed out against ramped up tensions caused by the US and reminding Washington “The South China Sea is not the Caribbean. It is not a place for the US to behave recklessly.” (Global Times, February 23). Just as China views the South China Sea as a core national interest, Washington views the Caribbean as naturally within its sphere of influence. Success in connecting America’s backyard to the Belt and Road Initiative presents a way for Xi to position China to challenge America in its own hemisphere.

Jared Ward is a Ph.D. Candidate and Associate Lecturer at the University of Akron in the Department of History. His dissertation and research focuses on China’s foreign relations with the Caribbean during the Cold War.

Notes

- Peter J. Meyer “US Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean: FY 2016. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R44113.pdf. January 7, 2016, Congressional Budget Office

- Author’s Private Collection