The Maute Brothers’ Path to Militancy in the Islamic State Inspired Fighting in Mindanao

The Maute Brothers’ Path to Militancy in the Islamic State Inspired Fighting in Mindanao

On May 23, 2017, Islamic State (IS) forces invaded the town of Marawi in Mindanao, Philippines. At first, it was unclear whether reports of the invasion were an exaggeration. However, after the fighting persisted for more than one month, with over 200 Maute militants and nearly 20 Philippine security forces reportedly killed, it became clear the battle was more than an IS “publicity stunt” (gmanewsnetwork, June 18). Moreover, both Islamic State videos and statements and local reports made clear that a Marawi-based group led by the Maute Brothers, who pledged baya’a (loyalty) to Islamic State, were behind the operation in Marawi. Islamic State also widely promoted the fighting in Marawi as the highlight of its magazine, Rumiyah (Rome), in June 2017 (Rumiyah, June 7).

But who are the now internationally notorious Maute Brothers who led this operation?

Path to Militancy

The Maute Brothers’ path to militancy began innocently enough. As teenagers in their native town of Butig in Lanao del Sur in the 1990s, according to those who knew them, they “seemed like ordinary young men… they studied English and the Koran, and played basketball in the streets” (Gulf News, June 19). Both of them even studied at a Protestant Church-run school, making their turn to killing Christians in the streets of Marawi during this operation seem contradictory (Inquirer.net, June 19). But their trajectory evidently changed in the early 2000s, when the two brothers—Omarkhayam and Abdullah—traveled to Egypt and Jordan, respectively, for religious studies.

Omarkhayam Maute studied at al-Azhar University in Cairo. There he met and married the daughter of a conservative Indonesian cleric, returning to Indonesia with her after they married. Those who knew him in Cairo never saw Omarkhayam as an extremist, however. He was known to enjoy spending time with his baby daughters and taking vacations by the Red Sea. (Gulfnews, June 12). A Philippine diplomat recalled that “he seemed to me like the typical devout Muslim, judging by what he was wearing. He had a turban and a goatee… I wouldn’t say at the time that he came across as a radical” (Straitstimes, May 26). Omarkhayam left Egypt for Indonesia with his wife and taught at her father’s school in Indonesia until 2011, when they settled back in Mindanao. It appears once in Mindanao he moved toward the path of militancy (Gulfnews, June 12).

Abdullah Maute’s life after Jordan is more obscure. One theory is that he also went to Indonesia when his brother was there, and that is when both Abdullah and Omarkhayam met Ustadz Sanussi, a fugitive Indonesian Jemaa Islamiya (JI) member (Inquirer.net, June 19). Sanussi placed the two brothers in contact with other Southeast Asian militants such as the Mindanao-based Zulkifli bin Hir (a.k.a. Marwan) (see Militant Leadership Monitor, April 29, 2015). Sanussi returned with the Maute Brothers to Mindanao, where he was subsequently killed along with six other JI members in 2012 (Inquirer.net, November 24, 2012). The location of Sanussi’s death was telling: he was killed in a safe-house owned by the Maute’ Brothers’ father, Cayamora Maute, who is an engineer. Investigations showed that the Maute family was aiding the transfer of JI funds from Indonesia to Sanussi through their bank accounts (Philstar.com, May 29).

Family and Militant Influences

The Maute Brothers, now connected to the JI and Abu Sayyaf networks in the Philippines, took over from Sanussi after his death with the formation of the “Maute Group.” Once in charge, the Maute’s family background and the environment—both locally and internationally—seem to have played a big role in their push toward jihadism. The Maute Brothers’ mother, Farhana, who owned a furniture and used-car businesses, helped to finance the two brothers and recruit local youths to their group. Thus, she was seen as the “heart of the Maute organization” (Philstar, June 11).

Similarly, Omarkhayam and Abdullah’s older brother, Mohamadkhayam, is married to the daughter of the former Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) vice chairman for Military Affairs and graduated with a degree in civil engineering. He is now reportedly directing the operations and intelligence of the Maute Group. (Philstar.com, May 29). Given this family connection to militancy, at the onset of the operation in Marawi, the Philippine security forces arrested the Maute Brothers’ father and mother, Cayamora and Farhana Maute, for their role in financing and preparing the logistics of the operation (Rappler, June 15).

Indeed, the Maute Brothers’ path seems to have gone through the MILF. When MILF signed a peace agreement with the government in 2010, a Saudi-educated elder MILF commander, Ameril Kato, set up his own his group that rejected the agreement. His group known as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) was based in Maguindanao with an estimated 300 fighters (Kato claimed to have up to 5,000 fighters) (Inquirer.net, February 1, 2015). The Maute Brothers reportedly sent representatives to visit Kato in his hideout in a secluded area of Maguindanao’s South Upi region after he suffered a hypertensive stroke that left half of his body paralyzed and eventually caused his death (Philstar.com, May 25). Kato died in 2015, which is just the time when the Maute brothers coopted some of his fighters in the direction of the then rising Islamic State (Inquirer.net, April 14, 2015).

Planning the Operation

Two precursors to the operation in Marawi occurred in February 2016, when the Maute Group beheaded a Philippine army officer in Butig and then, in April 2016, beheaded two Christian workers in an attack that was claimed by Islamic State. Then, in September 2016, the Maute Group detonated a bomb in Davao, Mindanao, killing 14 people. (abs-cbnnews, October 7, 2016). This prompted the Philippine military to launch an offensive in Butig in November 2016. A military spokesman said at the time: “The mission is to flush out the group and neutralize the enemies and to bring back normalcy to the area. Before we can achieve that, there will be a series of operations” (Rappler, November 26, 2016).

With connections to Abu Sayyaf via Sanussi and to some of the hundreds of fighters under Kato, by 2015 the Maute Brothers were able to connect with IS. This was facilitated by a longtime Abu Sayyaf leader dating back to the early 2000s, Isnon Hapilon, who had a direct connection to IS and was named its “amir over the Soldiers of the Caliphate in the Philippines” (in later publications all of “East Asia”) (al-Naba #67, February 9). Hapilon had pledged allegiance to IS as early as July 23, 2014, just after Abubakar al-Baghdadi declared the Caliphate, which Hapilon reiterated in another pledge in January 2016 (Twitter, August 12, 2014; (Twitter, January 4, 2016).

Some Philippine experts believe that during the Tablighi Jamaat convention in Marawi, which began one day before the Maute Brothers’ operation in Marawi, foreign fighters were able to enter the city. Since then, 40 Indonesians and dozens of Malaysians and Singaporeans have been reported in the ranks of the Maute Brothers (Philstar.com, June 5; Straitstimes, June 4). Experts believe that “actual” IS fighters from Southeast Asia could have snuck into Hapilon’s island bases in southern Mindanao. However, Middle Easterners would have needed a more legitimate cover, such as attending the Tablighi Jamaat convention, to enter a more mainland location like Marawi in Lanao del Sur (Inquirer.net, June 3).

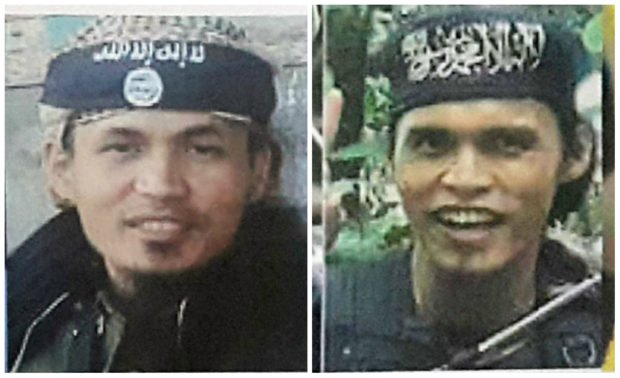

Indeed, while the Maute Brothers may have been the leaders of the operations in Marawi on-site, Hapilon seems to have been the mastermind of the operation. On June 7, photos surfaced of Hapilon with the Maute Brothers in Marawi apparently planning the operations in the city (gmanetwork.com, June 7). In response to their collaboration, Philippine President Rodrigo Dutarte issued a new bounty for Hapilon’s capture as well as new bounties on both Maute Brothers (Inquirer.net, June 6). Nonetheless, one month into the operations, Hapilon and the Maute Brothers still remain at-large. Although the Philippine military claimed on June 23 that the Maute Brothers were “very likely” killed, no evidence was provided. At the same time, the Maute Brothers have provided no counter-proof that they are live. If anything, unless one side confirms their fate, the Maute Brothers’ mystique may even grow (Philstar, June 23).

Regional Context

The Maute Brothers pulled off the most brazen operation in Southeast Asia in recent memory—perhaps only the Bali Bombings by JI in 2002 and 2005 were larger in scale, but those were one-off attacks. The operation in Marawi, in contrast, is the first time in Southeast Asia since the growth of jihadism after the September 11, 2001 attacks that jihadists have occupied a town for an extended period of time. With an al-Qaeda that is increasingly quiet in Southeast Asia, this operation is a big propaganda score for Islamic State. Moreover, it shows that what remains of al-Qaeda’s old networks in Southeast Asia, especially JI and Abu Sayyaf, have now become part of the Southeast Asia network of Islamic State.

Another important aspect of this operation is the Maute Brothers’ ability to garner several hundred fighters to their cause. In this respect, if future negotiations with MILF do not succeed or MILF fighters are inspired by the success of the Maute Brothers, it could lead more MILF fighters to defect. This would be a big boon for the Maute Brothers, who already appear to have significant local support around Marawi and international support from Islamic State but lack a broader national-based movement. With the defection of MILF fighters to the Maute Group, it could bolster the claims its fighters are already making in propaganda videos that they are Islamic State’s “East Asia Province” (the designation has not been made formally by Islamic State, however) and capable of carrying out and claiming multiple attacks. This would serve Islamic State’s interest in deflecting attention from its struggles in Syria and Iraq and highlighting its successes outside of the Middle East.