Tensions in Tehran-Baku Relations: Iran’s New Transit Routes in Armenia and the Caspian Sea

Tensions in Tehran-Baku Relations: Iran’s New Transit Routes in Armenia and the Caspian Sea

Although many observers assumed that the recent uptick in tensions between Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan (see EDM, October 6) would die down following the telephone calls between Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian and his Azerbaijani counterpart, Jeyhun Bayramov (Al Jazeera, October 13), subsequent public remarks by the latter country’s President Ilham Aliyev again incensed Tehran. In his comments at an October 15 session of the Council of Heads of State of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), Aliyev mentioned that Azerbaijan “has blocked a drug trafficking route from Iran through [the] Jabrayil district of Azerbaijan to Armenia and further to Europe” (Azernews, October 15). In reaction to this statement, Iranian Supreme National Security Council Secretary Ali Shamkhani said that, “Ignoring the principles and requirements of the neighborhood and making false and unconstructive statements is not a sign of good faith and prudence” (Mehrnews, October 15). Weeks earlier, responding to an interview the Azerbaijani president gave to the Turkish outlet Anadolu Agency, Iran’s foreign ministry spokesperson, Saeed Khatibzadeh, declared, “Aliyev’s remarks are surprising because they come at a time when Tehran and Baku have good relations based on mutual respect and there are normal channels through which the two sides can talk at the highest level” (Anadolu Agency, September 28).

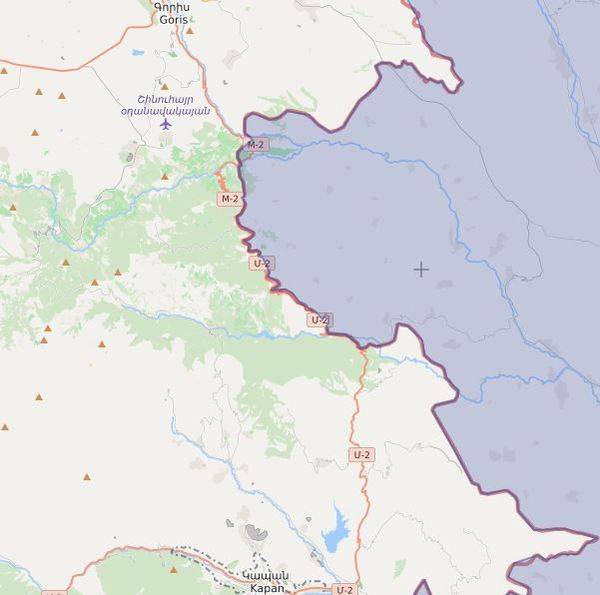

The recent antagonism between Tehran and Baku has had several consequences, including, notably, pushing Iran to seek out alternative transit routes to reach Armenia (and Georgia) as well as Russia. The catalyst was the Azerbaijani government’s decision to place restrictions on Iranian trucks traveling via the Goris–Kapan highway—a key segment of the main land route that links southern and northern Armenia and is part of a 400-kilometer road network stretching from Norduz, Iran, to the Armenian capital. Much of this highway straddles a disputed section of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border (see EDM, May 18, June 21) or turns deeply into Azerbaijani territory outright. Following the Second Karabakh War (September 27–November 9, 2020), roughly 21 km of that Soviet-era road in Armenia’s Syunik region, has been under Azerbaijani control.

Since early 2021, Azerbaijan has been setting up border guard posts and erecting signs reading “Welcome to Azerbaijan” on its sections of the highway and, on August 25, blockaded a section of it for nearly 48 hours. The situation was resolved with the help of Russian border guards, who patrol the Armenian side of the border (EurasiaNet, September 7). After these developments, Azerbaijan’s State Customs Committee stated that Iranian vehicles traveling along the Goris–Kapan highway are subject to a “state duty [$130] for the issuance of a permit regulating international road transport in the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan” (Customs.gov.az, September 13). Iranian truck drivers protested, saying that their destination was Armenia and not the Republic of Azerbaijan; moreover, they already have to pay a toll at the Norduz-Moghari Border Gate, on the border between Iran and Armenia, so they should not need to pay again. The vehement opposition and resistance of some Iranian drivers led to two arrests by Azerbaijani forces, further straining relations between Tehran and Baku.

In response, the Iranian government decided to define alternative routes to prevent the disruption of Iranian transit and trade with Armenia, Georgia, Russia and the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). The first alternative land corridor is the Tatev–Aghvani route, which entirely bypasses Azerbaijani territory. Iran has announced it would complete the unfinished portion of this road inside Armenia. And a technical delegation led by the head of Iran’s Construction and Development of Transport Infrastructures Company, Deputy Minister Kheirollah Khademi, visited Armenia to discuss completion of the Tatev–Aghvani route. Moreover, Iran has offered financial and technical support to Armenia, which plans to build a 550 km North–South Road Corridor that will traverse the entire country, beginning at the Iranian-Armenian border, but, critically, not cross into Azerbaijani territory (Fars News, October 4). Of course, it should be noted that the Tatev–Aghvani road was used prior to the recent developments along the Goris–Kapan highway. However, the Tatev–Aghvani route is notorious for its steep slopes and narrow passes that trucks have a difficult time traversing, particularly in rainy and snowy conditions. As such, the governments of Iran and Armenia hope to wholly reconstruct and improve the safety of this highway, specifically with truck transit in mind.

Iran’s second reaction to the Azerbaijani restrictions placed on the Goris–Kapan highway was to strengthen the Caspian Sea as a maritime alternative to the north-south land route across Azerbaijan to Russia. Thus, the director general of the Gilan Ports and Maritime Organization, Hamidreza Abaei, noted, “The destination of [Iranian] trucks carrying export goods is mainly Russia; a small number of trucks have Armenia and Azerbaijan as their final destinations. Given the problems created by Azerbaijan for Iranian trucks, the best-case scenario would be that all Iranian trucks reach Russia or Armenia directly by sea” (Eghtesad Online, October 6). To achieve this, Iran’s Trade Promotion Organization (TPO) signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) on cooperation in launching Caspian Sea shipping lines from Iran to Russia and Kazakhstan. Accordingly, in the first phase, six lines will be launched from the northern ports of Iran to the ports of Astrakhan and Makhachkala in Russia, as well as the port of Aktau in Kazakhstan as of October 23. In the second phase, by the end of the current Iranian calendar year (late March 2022), the number of these lines will increase to eight (Port News, October 15).

If the land corridor is important for Iran’s trade and transit with Armenia and Georgia, the maritime route is crucial for Iran’s transit and trade with Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union. In particular, negotiations are underway to convert the Iran-EEU Preferential Trade Agreement into a free trade agreement, which is expected to take effect in November 2022. Tehran is worried that its ability to increase the volume of trade with the EEU, especially Russia, will be hampered by restrictions on the land transit routes across the Caucasus.

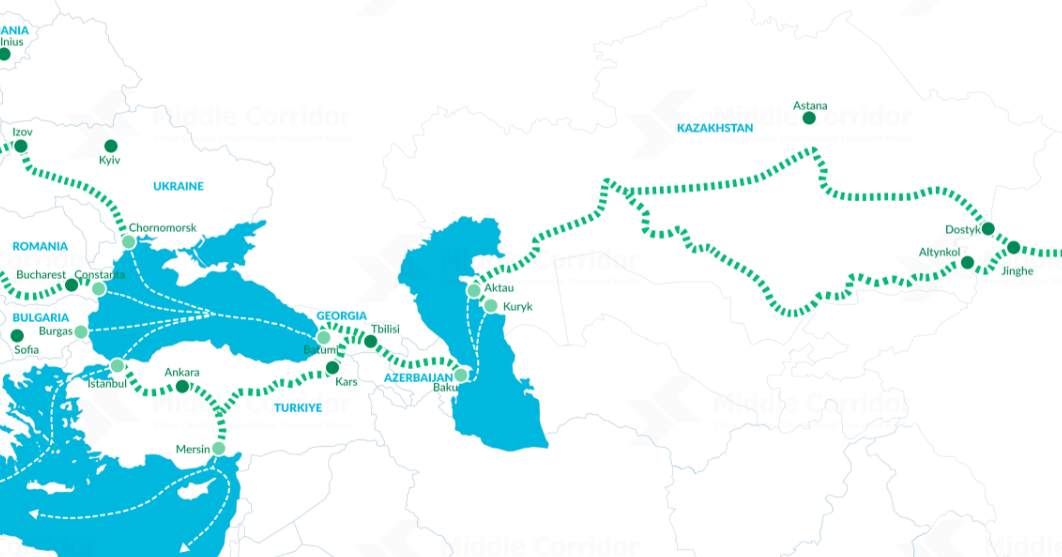

The outcome of the Second Karabakh War inadvertently brought to the fore old and new tensions and disputes between Iran and Azerbaijan. If these remain unresolved, they threaten to derail ongoing planning and development on multiple strategic, trans-border transit projects, including the North-South International Transit Corridor (Iran-Azerbaijan-Russia) as well as the completion of the Rasht–Astara railroad—the sole remaining rail piece of this corridor. In contrast, progress on the Tatev–Aghvani road promises to strengthen bilateral relations between Iran and Armenia, which were somewhat damaged during the Second Karabakh War, as well as facilitate the development of the Persian Gulf–Black Sea Transit Corridor via Armenia and Georgia.