A Profile of Northwestern Nigeria’s Kidnapping Duo: Nasiru Kachalla and Dogo Gide

A Profile of Northwestern Nigeria’s Kidnapping Duo: Nasiru Kachalla and Dogo Gide

Since Boko Haram claimed responsibility for the Kankara kidnapping in northwestern Nigeria’s Katsina State in December 2020, concern about banditry in the country has gained increasing national and international attention (see Terrorism Monitor, January 15). In the Kankara incident, the more than 300 schoolboys kidnapped from a school were subsequently released by bandits who had a link to Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau. However, many other targets of bandits have not been so fortunate. These victims have included Christian villagers, local village or political leaders, wealthy individuals whose family members have been abducted for extortion, herders whose cattle have been pilfered, and road passengers whose money and other belongings have been stolen.

The Kankara kidnapping bandits was reportedly were reportedly led by a man named Adamun Daudawa, and his accomplices were identified as Nashamuwa, Alhaji Auta, Na-Bajjallah, Dankarmi and Auwalu (Twitter.com/ankaboy, December 15, 2020). While they were known locally before the Kankara kidnapping, they lacked the prominence of two other leading bandits in northwestern Nigeria in recent years — Nasiru Kachalla and Dogo Gide. These careers of these two bandits are significant, demonstrating how northwestern Nigerian bandits mix criminal activities with jihadism while clashing with Nigerian security forces and rival bandits. Most of all, these bandits cause harm to local civilians who are in their way. The profiles, activities, alliances and rivalries of this bandit duo are detailed in this article.

Nigeria’s Bandit Duo

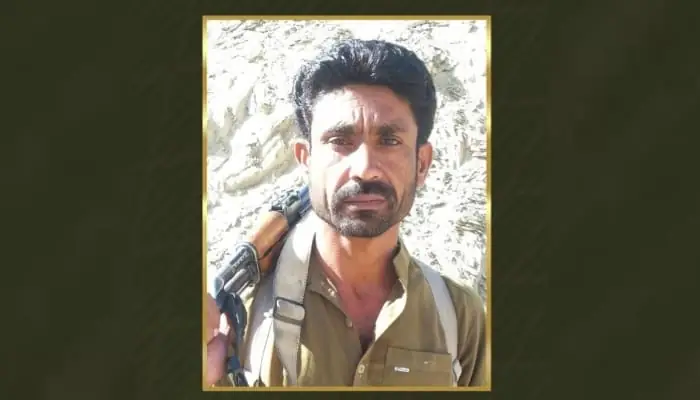

Nasiru Kachalla

Nasiru Kachalla was reported killed on December 28, 2020 in a clash with a rival bandit group in Kaduna State, which borders Katsina (pmnewsnigeria.com, December 28, 2020). Several kidnappings had been attributed to him by the security forces, including:

- the January 24, 2020 kidnapping of Bola Ataga, whose husband, Philip, is a prominent doctor, and their two children;

- the January 9, 2020 kidnapping of four seminarian students of Good Shepherd Major Seminary, Kaduna;

- the October 3, 2019 kidnapping of six students and two teachers at Engravers College in Kakau village of the Chikun local government, Kaduna.

Some of Kachalla’s methods can be gleaned from analyzing these operations. After kidnapping Bola Ataga, Kachalla’s bandits demanded a ransom of 150 million naira — nearly $400,000 (thecable.ng, February 2, 2020). Because the ransom was not paid, Bola Ataga was killed, and the bandits instead demanded $26,000 (10 million naira) for her two sons, which was paid. After the kidnapping, Philip Ataga financed the construction of a police station in his local community to help improve security there. Local youths also protested against the government’s failure to protect communities from the bandits. The demonstrations highlighted the deaths of Bola Ataga and a guard at her house who was killed when she was kidnapped (thecable.ng, February 1, 2020; thecable.ng, February 2, 2020).

The Good Shepherd Major Seminary kidnapping had a less tragic conclusion than the kidnapping of Bolo Ataga. The three seminarian students were released shortly after the kidnapping, with no report of a ransom being paid. However, it is likely that a ransom was paid but not publicly disclosed (Sahara Reporters, January 31, 2020). Nevertheless, the kidnappers reportedly released the first student after contacting his family, believing he was ill and would die in their hands (cathnews.com, January 21, 2020). The dormitory where the students were abducted hosted 268 students, although they were Christians, and not Muslims like the Kankara schoolboys (punchng.com, January 10, 2020).

This seminary kidnapping targeting Christians occurred after various Kaduna bandit groups began raiding Christian villages and abducting Christian leaders. Such raids have continued (thenationonlineng.net, December 27, 2020). It represents a sectarian angle to northwestern Nigerian banditry, even though the bandits, including Kachalla, rarely proclaimed Islam as their motivation, unlike jihadists. Nevertheless, it is common in Nigeria for Christians to attribute the scourge of banditry to “Fulani Muslims,” since many bandit leaders are Fulani and Muslim (crisisgroup.org, September 19, 2017).

Meanwhile, the Engravers College kidnapping resulted in a reported 10 million naira ($26,000) ransom being paid for the release of six female students and two teachers (premiumtimesng.com, October 26, 2019). This school was also Christian-run, and the targeting of students resembled the Good Shepherd Major Seminary kidnapping. Moreover, both of these kidnappings, and the kidnapping of Bola Ataga and her sons, were in Kaduna state’s Chikun local government area. Chikun, which was created in 1987 and is majority Christian with a significant Muslim minority, had managed to avoid the Muslim-Christian clashes plaguing the rest of Kaduna through political power-sharing (projects.harvard.iq.edu, 2013). However, Kachalla’s bandits threatened to disturb Chikun’s relative calm and showed how it was not only his victims who were harmed, but also the broader community.

Dogo Gide

While Kachalla’s tactics may have resembled those of jihadists, including Boko Haram, no reports have emerged pointing to him being involved with jihadism. Nevertheless, the al-Qaeda-loyal Boko Haram breakaway faction, Ansaru, which had been inactive since 2015, resurfaced in Kaduna in 2020 (thisdaylive.com, August 16, 2020). Ansaru’s most significant claimed operation was attacking a Yobe emir’s convoy that was passing through Kaduna. The attack killed several of the emir’s bodyguards before an operation by security forces forced Ansaru’s members to retreat (punchng.com, February 6, 2020).

It was Dogo Gide, not Kachalla, who reportedly established contacts with Ansaru and jihadists elsewhere in the Sahel (HumAngle, June 9, 2020). However, like Kachalla, he conflicted with rival bandit groups. Dogo Gide was reportedly injured in a Nigerian air force strike in June 2020, but those reports turned out to be false. At the time, Dogo Gide was attempting to arrange a ceasefire with those rival bandits so that they could form a unified bloc to fight the Nigerian military. However, not all of the bandit groups abided by the ceasefire, which led Dogo Gide to attack them. At this time, Kachalla, whose nickname was “Yellow,” was reportedly allied with Dogo Gide (HumAngle, June 14, 2020).

It was unclear if Dogo Gide was with Ansaru elements when he was injured (HumAngle, June 9, 2020). However, his forest hideouts and reported deputies from Zamfara overlapped with Ansaru. Ansaru founder Khalid al-Barnawi designated a Fulani deputy from Zamfara—who held his own weapons stash in Kaduna—to be his deputy before he was arrested in 2016 (thecable.ng, April 13, 2016). Ansaru also released photos of its fighters in a forested area when it once again announced its presence in Nigeria in October 2019 (Telegram, October 27, 2019). Ansaru and Dogo Gide were, therefore, operating in the same areas and all that was needed was for Dogo Gide to ally with Ansaru for them to find each other’s locations and coordinate. Presumably, Ansaru could provide tactical expertise to Dogo Gide’s bandits while the bandits could provide cover to Ansaru, helping it hide from the counter-terrorism pressure prevalent in other parts of the country.

After Dogo Gide was injured and due to his inability to unify the bandits to combat the security forces, he ended up calling for bandits to put down their weapons. He began preaching to local communities. He even went so far as to kill the most brutal bandit leader in northwestern Nigeria, Buharin Daji, although it is unclear what role, if any, Gide played in Kachalla’s death (punchng.com, September 21, 2019). Thus, although Dogo Gide caused much pain during his banditry career, his legacy is apparently becoming one of reform. At the same time, although Dogo Gide’s killing of Buharin Daji was intended to end the bandit leader’s ruthlessness and reign in northwestern Nigeria, the reality is it did little to improve local security (thenewhumanitarian.org, September 13, 2018). Moreover, it is unclear if Dogo Gide is committed to dialogue for the long-term, as it seems Ansaru appears to be lurking in the background of Gide’s latest talks with Nigerian Salafi scholar Ahmad Gumi (see Terrorism Monitor, February 26). Should such talks break down, Gide could again resort to attacks, with Ansaru by his side.

Conclusion

The cases of Nasiru Kachalla and Dogo Gide show the complex ways that Nigerian bandit leaders interact with each other, their communities, the Nigerian security forces and jihadists. A key difference between them and the jihadists is that they do not justify their violence in terms of establishing an Islamic state. Rather, they perceive themselves as victims of an unjust government, which compels them to engage in banditry and violate the law to sustain their livelihood. This may have correlations with, for example, piracy, either in the Gulf of Guinea off Nigeria’s coast or even off the Somali coast, where pirates justify their activities as necessary to respond to government and international companies’ violations of their coastal waters and fishing rights.

Given the growth of banditry in northwestern Nigeria, and the inability of the Nigerian security forces to curb it or the corruption and inequalities that facilitate the problem, new leaders like Nasiru Kachalla and Dogo Gide are likely to emerge. If these cases show anything positive, it is that bandit leaders may be willing to negotiate and even put down their arms. This is easier than with jihadist leaders, especially Shekau, because bandits are mostly interested in improving their lives here on earth, whereas Shekau’s top consideration is fighting for jihad and heaven in the afterlife. This means there may be opportunities for local civic actors, including village chiefs and religious leaders, to work together, engage bandits and find ways for them to put down their arms.

However, as Shekau and his larger rival, Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP), attempt to recruit bandits to their cause and preach among them, there is a risk that they will become increasingly enmeshed with jihadists, who are now mostly active in Nigeria’s northeast. This makes the consequences of not reigning in banditry even more pressing. This explains why Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari has publicly identified banditry as a security crisis equal to that of jihadism (guardian.ng, January 9).