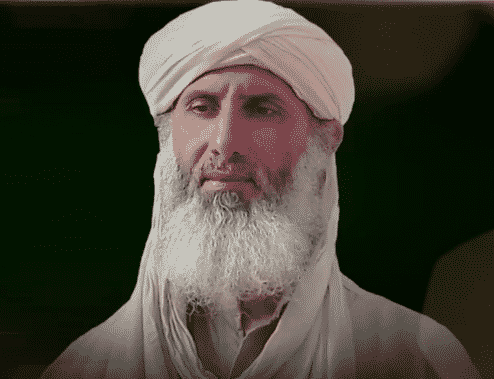

Al-Qaeda’s Influential Online Strategist: Abu Sa’d al-Amili

Al-Qaeda’s Influential Online Strategist: Abu Sa’d al-Amili

Though the writings of online jihadist strategists are readily available, analysts have struggled with what use to make of them due to the secrecy that surrounds these writers. Are jihadists in the field likely to heed their advice? Or are these men keyboard warriors blowing off steam, whose pronouncements will do little to sway al-Qaeda and its fellow travelers?

One of the most prolific online jihadists is Abu Sa’d al-Amili, who has for over a decade provided a great deal of strategic guidance, with a focus on North Africa. Al-Amili is interesting because he writes with an air of authority and recent revelations confirm that he is an important figure in Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). After AQAP admitted in July 2013 that its deputy amir Said al-Shihri had been killed by a drone strike, jihadists revealed a great deal of information about al-Shihri, including the fact that he posted in online forums under the alias Abu Asma al-Kubi. The revelation of al-Shihri’s identity demonstrates that operational leaders participate in online fora. It is thus conceivable but unproven that al-Amili may have an operational role.

Al-Amili’s connection to al-Shihri suggests al-Amili’s importance to AQAP. Al-Amili wrote the introduction to a compilation of Shihri/Kubi’s writings, entitled From the Heart of the Frontlines, which was posted in early 2013. [1] The fact that al-Amili was chosen to write the introduction says something about his status. The introduction also makes clear that he knew who Kubi really was, as al-Amili revealed, for the first time, that Kubi was “one of the people of the frontlines.” Another indication of al-Amili’s high-level knowledge is his involvement in a disinformation operation following false rumors of Shihri’s death in January 2013. At the time, both al-Amili and another senior online jihadist, Abdallah bin Muhammad, confirmed al-Shihri’s death. But in April tweets, al-Amili “officially confirmed” that al-Shihri was alive and suggested his previous claims were designed to mislead authorities, boasting that the “cunning” of the mujahideen had delivered “a powerful blow to the enemies of God.” [2]

The news that al-Amili is likely important within AQAP casts his writings in a new light. A review of his work reveals a figure who has evolved from general exhortations to more specific and actionable advice directed to specific al-Qaeda affiliates. Further, al-Amili’s writings provide a strong indication of the strategies that Salafi-Jihadist groups would actually adopt to exploit the Arab uprisings.

Background

Al-Amili’s writings have appeared in jihadist publications since at least 2002. His earliest known article in a jihadist publication appeared in a September 2002 commemoration of the 9/11 attacks, which al-Amili described as being solely religious in nature. [3] Though al-Amili is often described as “shadowy” due to the sparseness of biographical details, a review of his writings provides some important information.

Though he appears to now be in Yemen, al-Amili claims to have lived in Denmark; in December 2007 he specified that country as his place of residence. [4] If he was located in Europe (a claim that has not been confirmed), al-Amili seems to have left for more active fields of jihad between then and November 2009. In that month, the jihadist online forum Shumukh al-Islam advertised a question-and-answer session with al-Amili, allowing users to post questions for him—an honor typically reserved for recognizable online clerics. Around the same time, Shumukh al-Islam set up a sub-forum dedicated to al-Amili’s writing. Al-Amili was clearly gaining prominence on the jihadist web and his writing became more focused and less general. These changes are likely attributable to liaising with established jihadist groups. When he participated in the Q&A session, al-Amili explained at length why he provided minimal biographical details, suggesting that he made this decision because he was involved in operational work. [5]

Al-Amili seems to be considered a religious authority by jihadists who know him. In comments they contributed to a book that compiles al-Amili’s answers to his Shumukh al-Islam Q&A, jihadist figures Abu Ahmad Abd al-Rahman al-Misri and Abu Ayyub al-Ansari both refer to him as “our honorable shaykh.” However, al-Amili’s theological education is likely unimpressive. Like another jihadist figure concerned about his own meager qualifications, Abu Yahya al-Libi, al-Amili stresses the battlefield as the true path to qualification as an imam. [6]

Given the lack of biographical detail about al-Amili, one may ask if he is in fact a persona (perhaps the name used by a collective of jihadist thinkers) rather than an actual individual. This possibility is unlikely. For one thing, al-Amili has written publicly for over a decade, and when he started out, he was neither prominent nor particularly prolific. If AQAP or another group were creating a persona, they are unlikely to have taken so much care to establish a backstory. The bottom line is that al-Amili’s life and work follows the trajectory of a real person: he gained prominence over time, gradually established relationships with other senior jihadist figures and his thoughts continued to evolve in the way that a real person’s do.

Strategic Ideas

Al-Amili’s early writings contained several core ideas that would later influence how he believed al-Qaeda could exploit the Arab uprisings. He has long believed that the movement should be judged not just by its mujahideen, but also by its relationship to multiple segments of the Muslim community. In November 2007, for example, he wrote an article dedicated to those who gave the mujahideen money and support, a topic that would also factor in his writing the following year. [7]

One of al-Amili’s earliest reactions to the Arab uprisings, in April 2011, delineated the various factions to which the jihadist movement had to relate. [8] One faction was the Ansar (supporters), who are not on the battlefield but “have become an indivisible part of the body of jihad.” He saw the uprisings as an opportunity to expand the pool of Ansar. Another faction that al-Amili commented on was the “moderates,” who ideologically are midway between al-Qaeda and its enemies, and whose exhortations often discourage the mujahideen. Though al-Amili viewed this group negatively, he suggested that “we can channel their listening habits,” persuading them at least to end their hostility—and perhaps swaying some moderates to join the mujahideen. Probably the most important faction was what al-Amili dubbed the spectators, who have “considerable weight in the field.” Al-Amili believed that “as the mujahideen advance to the final victory,” the spectators would rush to support them.

Al-Amili actually articulated his basic approach to the Arab uprisings in June 2010, before the revolutions began. At that time he described “a new kind of knight,” who can prove his merit “in the fields of dawa (call to Islam), hisba (verification), and jihad.” [9] He re-emphasized the importance of dawa in January, 2011 as various groups were trying to situate themselves with respect to the revolutions. [10]

Conclusion

The pillars of dawa, hisba, and jihad would indeed become central to jihadist strategy in transitional countries like Tunisia and Egypt for the first couple of years following the fall of the old regimes, since the movement came to enjoy unprecedented opportunities to spread its message. In turn, hisba was manifested in vigilante violence aimed at perceived enemies of the movement but falling short of making war on the state. In this way, Salafi-Jihadists believed they could intimidate their foes without prompting a state crackdown (though Tunisia’s Salafi-Jihadists took it too far with the assassination of the left-leaning politician Muhammad Brahmi).

Al-Amili emphasized that a focus on dawa and hisba was in support of jihad, rather than in lieu of it. He said that jihadists should “hold on to their weapons and never neglect them,” an approach that Tunisia and Egypt’s jihadists embraced even while their strategies focused on dawa. [11]

In addition to his general advice for navigating the environment brought by the Arab uprisings, al-Amili has also provided specific advice to regional groups. One Salafi-Jihadist group on which he has focused is Ansar al-Shari’a in Tunisia (AST). An article al-Amili published in May 2012, for example, urged AST to adopt “constructive patience” until Tunisians were fully ready to embrace Salafi-Jihadism. Al-Amili also tried to guide AST as Tunisia’s government became increasingly confrontational; by November 2012, he advised the group to be ready to fight with “sword and pen,” a statement that represented a reversal of his previous encouragement that Tunisian Salafi-Jihadists should refrain from violence.

Just as al-Amili counseled, jihadist strategies in North Africa are now changing as Tunisian and Egyptian jihadists find themselves in greater confrontation with the state. Al-Amili will surely continue to weigh in on approaches these groups should adopt; and when he does, analysts should listen.

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross is a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and an adjunct assistant professor in Georgetown University’s security studies program. He is the author or volume editor of twelve books and monographs, including Bin Laden’s Legacy (Wiley, 2011).

Notes

1. Abu Sa’d al-Amili, introduction to Abu Asma al-Kubi, From the Heart of the Frontlines: Religious Teachings and Jihadist Incitement, Part 1, posted to Ansar al-Mujahideen Network, 2013.

2. See Amili posts on Twitter as @al3aamili.

3. Abu Sa’d al-Amili, “Educational Pause,” in Kitab al-Ansar no. 1, Sept. 2002, pp. 51-64.

4. Al-Amili made this claim on his now defunct blog, which could be found at alaamili.maktoobblog.com.

5. Abu Sa’d al-Amili, Reflections and Guidance on Operational and Jihadist Queries, posted online Feb. 2, 2010. This 198-page book compiles al-Amili’s answers during the Q&A session that he undertook for Shumukh al-Islam.

6. Abu Sa’d al-Amili, The Raids of New York and Washington: Benefits and the Required Role (Al-Ma’sadah Media Production Establishment, 2010).

7. Abu Sa’d al-Amili, “Be Gold’s Helpers,” Sada al-Jihad no. 20, posted Nov. 16, 2007; see also Abu Sa’d al-Amili, “Factors and Conditions of Renaissance,” Sada al-Jihad no. 31, posted Dec. 18, 2008.

8. Abu Sa’d al-Amili, “The Influences of al-Qaeda Attacks on the Psyche of People,” posted to the Hanin forum, Apr. 26, 2011.

9. Abu Sa’d al-Amili, “May God Accept Your Sacrifice, al-Maqdisi,” posted to Shumukh al-Islam, June 13, 2010. Dawa (proselytism) and jihad should already be familiar concepts to most readers. Hisba, or the obligation of “commanding right and forbidding wrong,” is an important Islamic concept. While Salafi-Jihadist groups believe that hisba necessitates violence, this kind of violence is categorically distinct from jihad, which is carried out against external enemies of the faith. In contrast, “forbidding wrong” suggests that the objects of these efforts are already a part of the Muslim community.

10. Abu Sa’d al-Amili, “Assault Them at the Proper Gate… Victory Will be Yours,” Ansar al-Mujahideen network, Jan. 31, 2011.

11. Abu Sa’d al-Amili, “Shari’a Clari?cations and Highlights on the Two Revolutions in Libya and Syria: Episode One (the Libyan Revolution),” published by al-Ma’sadah Media Production Establishment, Aug. 26, 2011.