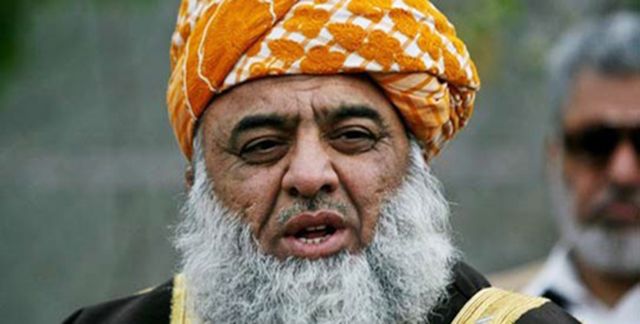

From Islamist Agitator to Taliban Target: Pakistan’s Maulana Fazlur Rehman

From Islamist Agitator to Taliban Target: Pakistan’s Maulana Fazlur Rehman

Early Life and Education

Maulana Fazlur Rehman was born into a religious family in 1953 in Dera Ismail Khan, one of the more underdeveloped areas in Pakistan. His ancestors came from Kandahar. Due to the severe and harsh winters in Kandahar, they would migrate to Dera Ismail Khan during winter months and return to Kandahar in the spring. When the grandfather of Maulana Fazlur Rehman fell ill and subsequently abandoned the migrant life, he settled in Dera Ismail Khan where he gave his son, who later became known as Mufti Mehmood, a religious education. [1] Mufti Mehmood studied in the local madrassa in Dera Ismail Khan and went to Darul Uloom Deoband (now in India) for higher Islamic studies. After completing his studies at Deoband, Mehmood returned to his village and started his career as an imam in the local mosque but later joined madrassa Qasimul Uloom in Multan (South Punjab) as a teacher and mufti (one who is authorized to give fatwa-s).

Maulana Mufti Mehmood, the father of Maulana Fazlur Rehman, was a prominent Deobandi cleric and politician who had opposed the partition of British India and the creation of Pakistan on religious basis. However, he later accepted it as a political reality. [2] Following Pakistani independence, Mehmood joined the Jamiat Ulama-e-Islam (JUI), a party founded by Deobandi ulema who had decided to stay in Pakistan. In 1956 he became the vice president of the JUI and later won the 1962 general elections. In the 1970 general elections, Mufti Mehmood won again, defeating Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Later, he joined the Provincial Assembly and was elected Chief Minister of Northwest Frontier Province (now known as the Khyber-Pukhtoonkhwa Province).

Maulana Fazlur Rehman began his childhood studies at home before his father placed him in a local elementary school in Dera Ismail Khan. He was later sent to a middle school in the ancient Sufi city of Multan, where he also graduated from high school. After completing his studies, Rehman’s father called him home and entered him into a madrassa where he completed his religious education. After finishing at the madrassa, he began teaching at the madrassa Qasimul Uloom in Multan. [3]

Maulana Fazlur Rehman Enters Politics

Although Maulana Mufti Mehmood had not initially been opposed to General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq’s martial law regime, he was not happy when General Zia reneged on his promise of holding free and fair elections after hanging Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1979. At the time of his death in 1980, Mehmood was holding consultations with his JUI party leaders about whether to oppose Pakistan’s Martial Law regime in light of the former prime minister’s brutal execution. He did not oppose General Zia because a large section of the JUI was still in support of the general, and any withdrawal of support would have divided the JUI. As happens in many prominent South Asian religious and political families, Maulana Fazlur Rehman replaced his father both as a politician and cleric in the dynastic tradition. Rehman could not be elected the amir of the party because many of the members of its ulema considered him too young and inexperienced. Despite this perception by his elders, he was eventually elected the general secretary of the party. Rehman remained the de facto head of the JUI because of his family background and the Central General Council of the JUI eventually elected him the central amir.

Though Maulana Fazlur Rehman inherited his father’s political clout when Mehmood died, Rehman chose to oppose the military dictatorship from the outset of his political career. Less than a month after his father’s death, Rehman severely criticized General Zia in a speech given in Karachi at a function held to condole his father’s death. He repeatedly criticized the regime thereafter. In the early 1980s, several parties, including the Pakistan People Party (PPP), decided to form a political alliance to oppose Zia’s military dictatorship. The PPP invited the JUI to join the new alliance. Rehman supported the alliance, but a large number of the JUI’s central leaders did not. Consequently, in 1981 the JUI broke up into two factions due to disagreement over whether or not to support the Zia regime. The faction led by Rehman became know as the Jamiat Ulama-e-Islam-Fazlur (JUI-F) while another religious leader named Sami-ul-Haq formed the Jamiat Ulama-e-Islam-Sami (JUI-S) (see Spotlight on Terror, May 23, 2007). [4] The majority decided to join the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) and joined Rehman’s JUI-F. Rehman remained steadfast in his opposition to the Zia regime and was repeatedly arrested in the years subsequent. The alliance Rehman forged with the PPP lasted until 1996 when the Pakistan Army dismissed Benazir Bhutto’s government for the second time.

Maulana Fazlur Rehman and Electoral Politics

As popular pressure mounted on the regime to return to democracy, General Zia announced that he intended to hold party-less general elections in which politicians could run on individual platforms but not as candidates of any established political parties. The MRD decided to boycott Zia’s proposal as a matter of principle. The experiment in democratization ultimately failed. General Zia’s handpicked prime minister, Muhammad Khan Junejo, turned on him. Zia dissolved the government and parliament in May 1988 but soon after died in a mysterious plane crash in August 1988. All political parties, including the JUI-F, took part in the general election that followed and JUI-F emerged as the most popular Islamist political party in the country. [5]

The Rise of Maulana Fazlur Rehman—Chair of the National Assembly’s Foreign Affairs Committee

As a result of JUI-F’s political alliance with the PPP, Maulana Fazlur Rehman and his party voted for the PPP’s presidential candidate, Sardar Farooq Ahmed Khan Leghari, after the 1993 general elections. Since the support from the JUI-F members in parliament was crucial in the election, the PPP had to accept a number of conditions from the JUI-F, one of which was to help elect Rehman as the chair of the prestigious Foreign Affairs Committee of the National Assembly. The PPP followed through with their assistance and Rehman was elected the chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee on March 1, 1994. Although this committee is not as powerful as its equivalent in a Western country, it brought Rehman to the world stage. Another condition required the government to designate three ambassadors on the recommendation of the JUI-F. In addition, the PPP members in the Balochistan Assembly were to vote for the JUI-F candidate in the senate elections. The PPP was to also appoint JUI-F leaders as ministers in the federal cabinet and advisers in the Punjab and Sindh governments. [6]

The other conditions to which the PPP government was almost blackmailed into accepting related to the Islamization of Pakistan. They included the strengthening of the Federal Shari’a Court, making the Islamic Ideological Council (IIC) more powerful, and implementing Islamic laws based on the recommendation of the IIC. [7] This Islamization of the country was bound to have a great impact on law making because the PPP government had also agreed to nominate four JUI-F ulema in the IIC. The agreement also included a clause to keep the Islamic articles in the constitution intact and establish an Economic Council to replace the interest-based economy with an Islamic banking system. Another clause recommended the visit of a parliamentary delegation to Makran in Balochistan where a small Muslim sect called Zikris, who Sunni fundamentalists consider to be heretical, is based. The goal of the JUI-F was for Zikiris to be declared non-Muslims in the manner of Pakistan’s persecuted Ahmadi minority. [8]

Support for the Taliban

The election of Maulana Fazlur Rehman as the chair of the National Assembly’s Committee on Foreign Affairs and the amir of the JUI-F coincided with the beginning of the Taliban movement in Afghanistan. Since the movement was Deobandi in origin and many of the Taliban commanders had studied in the JUI-F-controlled madrassas in Pakistan, Rehman, with his considerable domestic political muscle, put all his weight behind the Afghan Taliban. A meeting of the central shura of the JUI-F in June 1996 extended its support to the Afghan Taliban who followed what many in Pakistan believed to be orthodox Islam. They have established peace in the territories they are ruling. The stability in Taliban-ruled territories is crucial for the Islamic laws to go unaffected. [9] Rehman played an important role in making the administration of the late Benazir Bhutto tilt in favor of the Afghan Taliban during her second term as prime minister from 1993 to 1996. In this capacity, Rehman also played an important role in generating support for the movement in other Muslim countries (BBC News, November 6, 2002).

Post 9/11 Period

JUI-F under Rehman reacted very sharply against General Pervez Musharraf’s decision to join the U.S.-led coalition in Afghanistan. Several JUI-F leaders, with encouragement from Rehman, excommunicated General Musharraf from Islam for supporting American interests in the fight against the Afghan Taliban. A prominent JUI-F leader and then head of Jamia Binoria in Karachi, Mufti Nizamuddin Shamezai, stated: “Musharraf openly supports the U.S. and its allies against Taliban. And under Islamic laws if any Muslim cooperates with infidels against Muslims, he must be excommunicated from the religion.”

Mufti Nizamuddin Shamezai was known for his close relations with al-Qaeda. The JUI-F called for strikes and demonstrations in Pakistani cities in support of the Afghan Taliban after the coalition forces and their Afghan allies ousted the Taliban regime in Kabul in late 2001. Many other Islamist parties supported these calls. Although there were protests across Pakistan, the demonstrations in the Balochi provincial capital of Quetta were particularly notable. Tens of thousands of madrassa students descended in the streets and paralyzed life in Quetta. The anti-U.S. demonstrations led by the JUI-F following Friday prayers in Balochistan have been part of its political strategy since the fall of 2001 (The Baloch Hal, April 2).

Friendly Opposition under a Military Regime

As soon as General Musharraf decided to hold elections in 2002, Islamist parties formed a new political alliance called Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA), with encouragement from the Pakistani military. The positions of the Islamist alliance and the Pakistani military on several issues were so similar that the MMA became popularly known as the Military-Mullah Alliance. Important components of the MMA are known to have had deep links with the country’s military. The MMA won the Provincial Assembly elections and formed the government in Peshawar, with a nominee of Rehman as the Northwest Frontier Province’s Chief Minister. In Balochistan, the MMA was also an important member of the governing coalition. The MMA Islamized the laws and radicalized societies in the two provinces that border Afghanistan (Newsline [Karachi], July 15, 2003). To keep the two most popular parties out of the political system—i.e. the PPP and Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz Sharif (PML-N)—the military helped the MMA general secretary, Maulana Fazlur Rehman, get elected to the office of the Leader of the Opposition in the National Assembly. Despite its role in the opposition coalition, the MMA helped the Musharraf regime pass the Legal Framework Order (LFO) that legitimized the military rule in lieu of the passage of their proposed Shari’a law bill (Ibid.).

Although Maulana Fazlur Rehman has been able to expand his political support base by cooperating with the military, he has failed to endear himself to the even more hardline Deobandi Pakistani Taliban who have emerged from the Federally Administered Tribal Areas in the last decade. The Pakistani Taliban exist in staunch opposition to the Pakistan Army, unlike the Afghan Taliban that Rehman supported who relied on Pakistan’s military establishment for succor. Two recent suicide attacks on Maulana Fazlur Rehman at the end of March, believed to have been carried out by the Pakistani Taliban, reflect the widening gulf between the traditional Deobandi Islamists seeking to operate within the boundaries of Pakistan’s entrenched political framework and the highly radicalized Deobandi jihadists who have set their crosshairs on the Pakistani state. Anyone who does not fit into this newer, increasingly harsh Deobandi paradigm, including a veteran Islamist stalwart like Rehman, remains a target for the Pakistani Taliban’s wrath (see Terrorism Monitor, April 14).

Notes

1. Shaykh Abdul Qayyum, “Maulana Fazlur Rehman ka siasi Safar” in Urdu, (Talagang, Punjab Province: Maktaba Farooqia, 1999), Pp 20-22.

2. Author interview with Maulana Fazlur Rehman, July 2002, Islamabad.

3. Ibid.

4. Author interview with Maulana Samiul Haq, February 2002, Akora Khattak.

5. Tabulated from the reports of the Election Commission of Pakistan from 1988 to 1997.

6. Author interview with a former PPP minister, October 1999, Islamabad.

7. Ibid.

8. Not all of these conditions were implemented in the final analysis.

9. Qayyum, op. cit., pp. 125-126.