Beijing’s Latest Global Leadership Bid

Executive Summary:

- The Global Governance Initiative (GGI), announced by Xi Jinping at the 2025 Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit, marks a strategic evolution from sectoral cooperation to competition for global governance leadership. It critiques the so-called “global governance deficit” (全球治理赤字), which lead to the underrepresentation of the Global South, and calls for a more equal global governance system.

- The GGI advocates reform in international institutions while attempting to establish emerging international mechanisms in various aspects, calling out frontiers such as artificial intelligence (AI), space, and deep sea. It also references current measures, such as the newly established International Organization of Mediation (IOMed), as the pathway for implementation.

- This new initiative completes the previous three Chinese-led initiatives, covering security, civilization, and development, providing an overarching framework that challenges the Western-led global order. While specific measures remain announced, the GGI reveals Beijing’s ambition to reshape international governance structures and establish alternative institutional arrangements, even as officials frame it as enhancing existing institutions and upholding UN principles.

The Global Governance Initiative (GGI), which General Secretary Xi Jinping unveiled in September, aims to provide “Chinese solutions” (中国方案) to what Xi describes as a “global governance deficit” (全球治理赤字). It uses inclusive rhetoric of improving existing governance mechanisms obscures a parallel institution building effort, which follows Xi’s articulated vision of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) as leader—not merely participant or advocate—in global governance.

GGI Discourse Criticizes the West

It seeks to confront three perceived weaknesses in contemporary global governance, including the underrepresentation of Global South countries in international institutions, the erosion of authority within existing governance frameworks, and what Beijing terms the “effectiveness deficit” (有效性赤字) in addressing transnational challenges. The GGI operates through five core principles: sovereign equality, international rule of law, multilateralism, people-centric governance, and action-oriented results. In his explanation of the initiative, Xi urged the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to become a “participant, advocate, and leader” (参与者、推动者、引领者) during this period of “revolutionary” (革命性) change in international power, and to actively participate in the formulation of international rules (PLA Daily, September 13; People’s Daily, September 26).

Official commentaries and opinion pieces released alongside the initiative explicitly criticize unnamed powers for withdrawing from United Nations treaties, cutting international funding, obstructing Security Council resolutions, and undermining WTO mechanisms. Calling out “hegemonic, domineering, and bullying tactics” (霸权霸道霸凌行径), including abuse of national security pretexts for sanctions, “long-arm jurisdiction” (长臂管辖) practices and creating exclusive “small cliques” (小圈子), these articles clearly refer to the West in general and the United States in particular (Qiushi, September 11; Xinhua, September 12; People’s Daily, September 15; Xinhua, September 16). Commentaries also emphasize that the GGI does not aim to “start a new venture” (另起炉灶), but to uphold multilateralism and strengthen global governance, especially addressing the underrepresentation of the Global South within international institutions (Wenhui Daily, September 14).

New Mechanisms to Shape Emerging Sectors

The GGI framework remains rather vague for now, but PRC diplomats have identified several domains within which to seek reform. In a speech, Deputy Permanent Representative to the United Nations Geng Shuang (耿爽) called upon more countries to join the International Organization for Mediation (国际调解院, IOMed), a newly established institution by the PRC based in Hong Kong. Geng positioned the organization as a valuable supplement to existing mechanisms for resolving global conflicts. PRC experts note that both reforming existing international mechanisms (改制) and building emerging international mechanisms (建制) such as the IOMed represent specific paths to improve the effectiveness of the GGI. They argue that the establishment of the IOMed aligns with the five core principles of the GGI by enhancing the representation of developing nations, adhering to international law, and providing a peaceful resolution to international disputes. The IOMed will also strengthen the capabilities of developing countries to enforce mediation and develop a work plan to promote its use, providing funds, scholarships, and training (The Paper, September 28; Xinhua, October 10).

In emerging domains such as artificial intelligence (AI), the GGI also aims to prevent the emergence of both of technology monopolies and risks such as algorithmic bias and autonomous weapons. According to official statements, this is to ensure that AI’s benefits become “public goods shared by all mankind” (全人类共享的“公器”). The GGI echoes the Global AI Governance Initiative (全球人工智能治理倡议), previously advocated for by Beijing, which called for the establishment of a Global AI Cooperation Organization (世界人工智能合作组织) to encourage cooperation, technology exchange, setting standards for data protection and security, and the establishment of a mutual recognition mechanism for model audits in key sectors such as finance, healthcare, and national defense (China Brief, September 5; Qiushi, September 28).

The GGI also includes ambitious financial governance reform targeting the dollar-dominated international monetary system and Western-controlled financial infrastructure. The governor of People’s Bank of China, Pan Gongsheng (潘功胜), stated that the GGI aligns with the need to reform the international monetary system and improve the cross-border payment system, noting that more countries are now using Renminbi (RMB) for settlement. Pan also called for governance reforms to international financial organizations like the International Monetary Fund to reflect the rising economic status and voice of emerging markets (Qiushi, September 16).

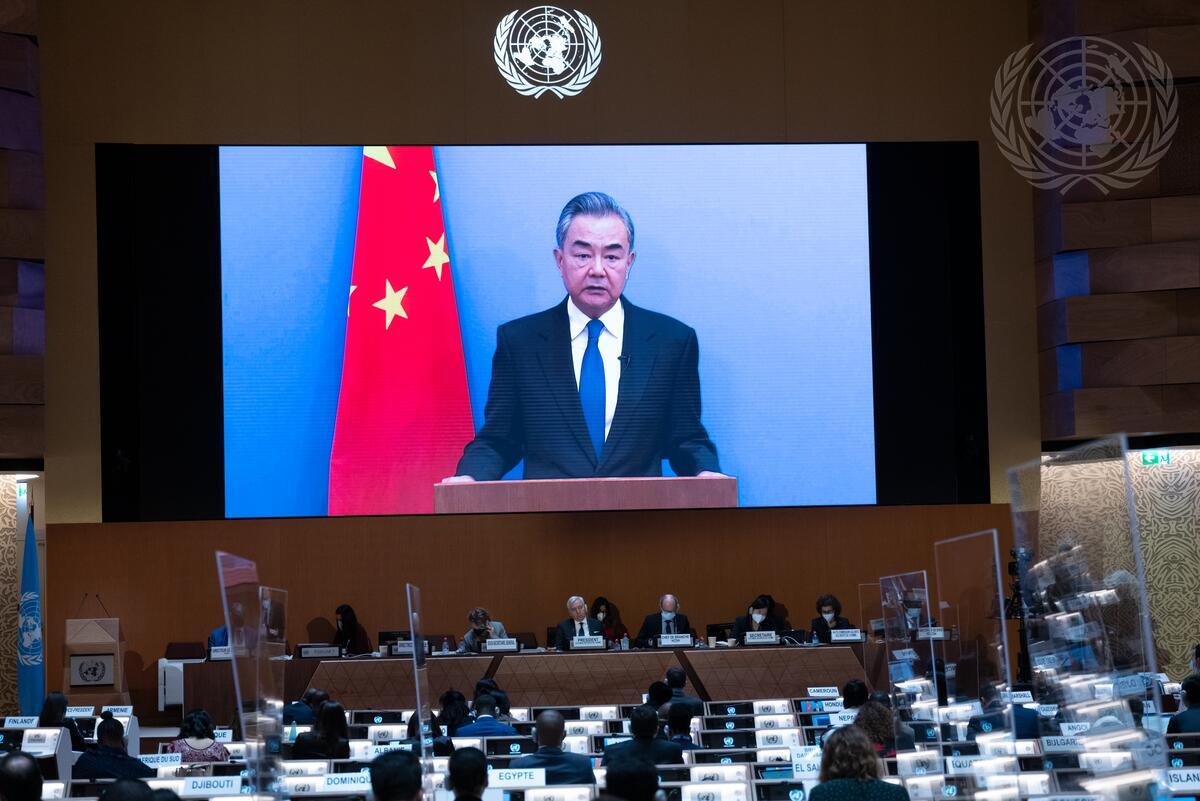

In late October, Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) and PRC Permanent Representative to the United Nations Fu Cong (傅聪) reiterated the PRC’s unwavering support for the United Nations. They claimed the GGI aligns with the purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter and provides a pillar of support at a time when the foundation of the United Nations is faltering. Wang cited examples of PRC support, including the establishment of a new “China-UN Global South-South Development Facility” (联合国全球南南发展支持机制) and the reform of the UN Security Council (UNSC) (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, October 27; Xinhua, October 25).

The GGI’s rhetoric of enhancing existing global governance structures obscures a more fundamental strategic objective. While officials claim these PRC-led entities complement existing frameworks, their governance structures, membership composition, and operational mandates suggest parallel systems designed to route around Western-dominated institutions where Beijing claims to be underrepresented. This institutional proliferation pattern contradicts the explicit claim of not creating a new venture, instead revealing Xi’s articulated vision of the PRC as the leader, not merely a participant or advocate in global governance.

Past Initiatives Fuel Beijing’s Confidence

The success of Beijing’s earlier global initiatives suggests that GGI has the potential to reshape global governance structures. The Global Security Initiative (GSI), for instance, has demonstrated remarkable traction in Africa, where Beijing has systematically embedded its security institutions into African partner countries through the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). Since 2022, Beijing has secured official endorsements from African governments, established joint law enforcement operations in multiple countries, and committed to training 6,000 senior African military officers by 2027. The GSI’s concrete implementation, including the creation of bilateral law enforcement centers like the Ethiopia-China Law Enforcement Center and joint operations protecting Belt and Road infrastructure, shows how PRC initiatives can move beyond rhetoric to demonstrate regional influence. But concerns were also raised against Beijing’s increasing export of domestic police wares, technology, and surveillance systems that have interfered in African governance, undermined democratic norms, and impacted civil liberties (Africa Center for Strategic Studies, August 4; China Brief Notes, September 30, 2024).

The GGI has garnered rapid endorsement from Russia, Malaysia, Slovakia, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Cuba, and dozens of other countries and international organizations. Russian President Vladimir Putin noted the GGI aligns closely with Russia’s view on Eurasian security (Kremlin, October 2). Even the UN’s leadership has welcomed the initiative’s multilateral focus (People’s Daily, September 15; China Daily, September 17).

The launch of the GGI coincides with the UN’s 80th anniversary and leverages the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) platform—an explicitly anti-Western institution—to signal Beijing’s solutions for alternative multilateral frameworks over Western-dominated institutions (Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs, September 4; Xinhua, September 12). This timing, along with the 80th anniversary of the Second World War, allows Beijing to position itself as the defender of multilateralism precisely when the United States appears to be retreating from global institutional leadership.

Conclusion

The GGI constitutes a fourth pillar of Beijing’s current global initiative framework, though additional global initiatives may be unveiled in future. Together, these pillars address what Beijing identifies as humanity’s fundamental needs: material development, security, cultural dialogue, and institutional governance (Shanghai Observer, September 14; China Daily, September 15). By positioning itself as putative leader, this approach demonstrates unprecedented strategic ambition across all dimensions of international relations.

Beijing persistently encourages other countries to verbally sign on to its initiatives. It has had comparatively little success to date, however, in incorporating its preferred language into UN resolutions or treaties. Desires to contribute “Chinese solutions” are therefore manifesting much more clearly through parallel institutions where the PRC exercises much greater control.

By appealing to the Global South, Beijing hopes to build a coalition that could alter international power dynamics. Its experience with GSI’s implementation demonstrates how these initiatives function as mutually reinforcing stepping stones for expanding influence across regions and sectors, providing tangible regional support in exchange for broader support on global governance. Grievances about the underrepresentation of the Global South have given traction to these PRC-led initiatives to become a competing pole of governance authority, ultimately challenging the more democratic institutions that exist today.