Death of Islamic State East Asia Leader Abu Dar Puts Philippine Militant Leadership in Flux

Death of Islamic State East Asia Leader Abu Dar Puts Philippine Militant Leadership in Flux

On June 28, a pair of suicide bombers (Rappler, June 29) struck a Philippine outpost, killing five and wounding nine. It was the third suicide bombing in a year, in a country that had so far not had any, raising fears of increased Islamic State influence. It comes at a time when IS cells in Southeast Asia are in flux, regrouping from the 2017 siege of Marawi, while IS in the midst of its own transformation following the loss of the caliphate.

On April 29, the leader of Islamic State (IS), Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, made his first video appearance in several years. While he discussed with his staff IS’ global operations following the loss of their Caliphate, he importantly did not mention the Islamic State in East Asia (ISEA), puzzling analysts. Was this simply an oversight? Or did it reflect frustration with the lackluster state of operations and current leadership void?

Starting in mid-2014, there was a gaggle of small militant groups and cells in Southeast Asia that pledged bai’at – allegiance – to al-Baghdadi. IS-Central never returned the recognition until early 2016, declaring the Abu Sayyaf leader, Isnilon Hapilon, to be the emir of the regional affiliate. Other groups were labeled “brigades.” A formal wiliyat, or province, was not declared until 2018, and only when IS began to lose significant parts of its territory in Syria and Iraq, and began to revert to a global insurgency model.

As IS-Central hemorrhaged territory in 2017-2018, IS militants in the Philippines began their five-month siege of the city of Marawi. That siege was planned and executed by Isnilon Hapilon, the Maute brothers, and Humam Abdul Najib, a.k.a. Abu Dar.

More than 1,000 were killed in the bloody fighting that marked IS’ most serious assault into Southeast Asia. It also saw IS releasing a slick video as part of its “Inside the Caliphate” series, calling on people to wage jihad in Marawi, drawing even more foreign fighters to the area.

The Mautes hailed from a family of Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) members, and had studied Islamic jurisprudence in the Middle East, before returning to Lanao del Sur and forming a group aligned with Islamic State — Khilafa Islamiyah. Hapilon, had brought his men from Basilan, an island where the Abu Sayyaf had made a strident comeback, after U.S.-assisted Philippine forces had declared the island pacified. Hapilon’s men engaged in savage fighting. Abu Dar had traveled to Afghanistan in 2005, where he was trained as a bomb-maker. In 2012, he returned to the Philippines, where he joined his cousins, the Mautes, in establishing Khilafa Islamiyah.

Islamic State announced the establishment of the Islamic State in East Asia (ISEA) wiliyat in July 2016, but sent very mixed signals about it, seemingly walking back their own announcement.

Hapilon and the Maute brothers were killed in the final days of the Marawi siege, along with a leading Malaysian militant, Dr. Mahmud Ahmad, but Abu Dar slipped out of the city and started to regroup his forces (New Strait Times, November 1, 2017; Rappler, March 5, 2018).

Dar sought to take advantage of the government’s botched reconstruction of Marawi and tens of thousands of disaffected displaced peoples, as well as skeptical combatants from MILF, who were opting out of the peace process with the government. Dar, the senior-most IS leader in the Philippines, was responsible for a number of attacks throughout 2018 (Benar News, September 7, 2018).

A large bounty was placed on Dar’s head, and his wife, Nafisa Pundug, was arrested in the southern city of General Santos in April 2018 (Benar News, June 22, 2018; Rappler, July 16, 2018).

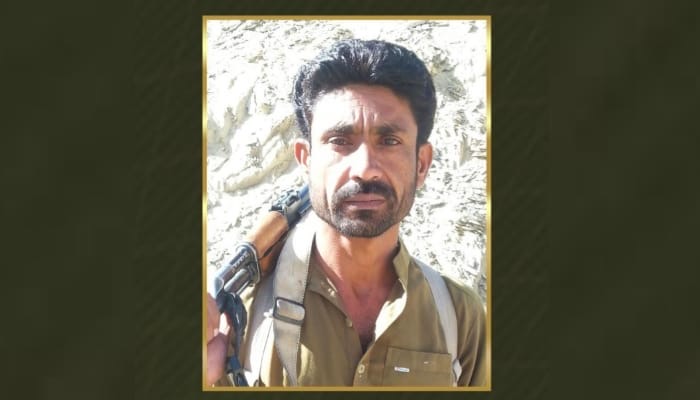

A March 14 gunfight that left three members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) dead, resulted in the death of Abu Dar. DNA tests confirmed his death a month later (Benar News May 14).

Dar was one of the rare militants in the southern Philippines who helped bridge the parochial splits among small militant groups, which tend to be organized along ethnic and tribal lines. He was responsible for infiltrating militants from Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Middle East into Marawi, giving him a leading role in maintaining international networks (Benar News, June 22, 2018).

Dar’s death has had a real impact on the course of the Islamic State’s operations in the Philippines. His IS cell was actively regrouping; it was engaged in small-scale offensive operations, and he was able to maintain the pipeline of men and resources from Southeast Asia to augment their ranks.

There is no clear successor to Abu Dar. But Furuji Indama and Hatib Hajan Sawadjaan are the figures to watch.

Furuji Indama, known for his brutality, hails from Basilan and emerged as Isnilon Hapilon’s deputy as the Abu Sayyaf regrouped in 2014. The most gratuitously violent acts in the country are invariably tied to him.

He was thought to be in charge of the group behind the beheading of 14 Philippine soldiers in 2014. Indama led a bloody attack in April 2016 that left 22 soldiers dead (Channel News Asia, October 17, 2017). In July 2016, in an attack that foreshadowed the siege of Marawi, Hapilon and Indama attacked and held a village in Tipo raising the Islamic State flag; displacing more than 1,000 people (GMA Network, July 7, 2016).

When Hapilon left Basilan in early 2017 with many of his men to join the Mautes for the first combined operation with another militant group under the Islamic State banner in Marawi, he left Indama in charge of Abu Sayyaf forces on Basilan. The violence escalated.

Indama was responsible for the beheading of seven loggers in July 2017, and the following month, his men attacked a village, destroying all government buildings, including a health clinic. Nine were killed and 10 wounded in the attack (Benar News, July 31, 2017; Rappler, August 21, 2017).

Indama is equal parts militant and warlord, with a penchant for extortion, especially of large-scale development projects (Rappler, August 1, 2018). The May 2015 beheading of a telephone company employee working for a project that ran through Indama’s territory was a clear signal that any commercial project in his territory can only happen with his blessing (Inquirer.net, May 4, 2015).

But Indama’s real threat may be in his role as the new conduit for foreign fighters in and out of the southern Philippines. In August 2017, Malaysian authorities arrested one of his top aides, Hajar Abdul Mubin, a.k.a. Abu Asrie, who was planning terrorist attacks in Kuala Lumpur (Rappler, September 3, 2017). A series of arrests in 2018 in Malaysia’s Sabah state, a critical transit hub in and out of Indonesia and Malaysia, exposed his reach. Malaysian police uncovered two large cells that were fundraising for him, moving militants, and providing other logistical support (Benar News, February 21, 2018).

In January and February 2018, Malaysian police arrested 10 people in Sabah; one of the seven Filipino members of the cell was a top aide of Furuji Indama (Channel News Asia, February 21, 2018). In March, two additional members of the Abu Sayyaf, including a trained bomb-maker tied to Indama, were arrested (Benar News, March 26, 2018). That November, Malaysian authorities disrupted an eight-person cell that included six members of the Abu Sayyaf and another aide to Indama (Benar News, November 16, 2018).

Indama’s Basian cell has been less involved with kidnapping for ransom than the Sulu faction, now headed by Hatib Hajan Sawadjaan (Associated Press, February 21), which has fully involved itself in kidnapping of both locals and foreigners, as well as maritime ship-jackings.

Sawadjaan’s cell was responsible for the 2015 kidnapping of two Canadians and a Norwegian from Davao. The former were executed in 2016, and in 2017, a German national was beheaded (SCMP, June 13, 2016). One of Sawadjaan’s key aides is Behn Tatuh, thought to be the man who executed the two Canadians and who is active on social media (Global News, December 20, 2018).

More importantly, Indama’s leadership within the broader Islamic State movement is not clear. Hapilon, until his death, was the emir of ISEA, and Indama was his deputy. But he remained in Basilan, running the ASG. Indeed, the current relationship between Islamic State and the Abu Sayyaf is unclear.

Two major terrorist attacks in the past year suggest that the key node between the Abu Sayyaf and IS Hatib Hajan Sawadjaan (AP News, February 21).

On July 31, 2018, a Moroccan man, Abu Kathir al-Maghribi, drove up to a checkpoint outside of Lamitan town on Basilan Island, detonating an ammonium nitrate bomb, killing 10 (Benar News, August 3, 2018). The fatalities included a soldier, five paramilitary members, and three civilians, among them a woman and a child. That operation was led by the Jolo-based Hatib Hajan Sawadjaan, a long-time Abu Sayyaf commander.

Then in January of this year, there was a double bombing at a cathedral during Sunday Mass on the island of Jolo (Rappler, January 28). The suicide bombings were perpetrated by an Indonesian couple, who had attempted to join the Islamic State in Syria before being returned to Indonesia. The pair had traveled to Sulu, where they joined Sawadjaan. IS claimed responsibility for the attack (Benar News, July 23). The attack killed 23 people and wounded more than 100.

The latest attack on a military outpost in Sulu, was allegedly the work of a pair of suicide bombers. Significantly, the bombers were Filipinos, the first from the country to engage in a suicide bombing (Benar News, July 2). But the third suicide bombing in less than a year certainly raises questions of whether this is being directed by IS, or a local commander like Sawadjaan is simply trying to make the case for an unequivocal declaration of a wiliyat. Amaq News Agency claimed credit for the attack. And the attack clearly reflects increased radicalization.

IS claimed responsibility for the attacks, though they were clearly supported by the Abu Sayyaf in their attack on Basilan Island, and they likely perpetrated the double bombing at the cathedral in Jolo. ISEA command and control, as well as coordination with the Islamic State’s central command, is unclear. But it is evident that Islamic State will rely more and more on regional affiliates to broaden the battlefield, as IS morphs into a global insurgency.

The U.S. Department of Defense believes that Sawadjaan is the acting emir of ISEA, but there is no official recognition of either him or Inadama from IS-Central.

Both Indama and Sawadjaan have a proven reach into Malaysia, in terms of both logistics and operations. Due to the death of militants such as Zulkifli bin Hir, Dr. Mahmud Ahmad, and Abu Dar, Sawadjaan has become the point man for foreign militants entering the Philippines for training and operational experience. Sawadjaan’s daughter married a Malaysian militant, Amin Baco, who was part of the Marawi siege. He is likely poised to take on a greater leadership position in ISEA.

As such, both Indama and Sawadjaan have become the AFP’s main targets (Benar News, April 24). Authorities have expressed concern that Indama has dispatched lieutenants to Manila to carry out terror attacks to pressure the government into ending its offensive. Authorities arrested two ASG operatives working on his orders in Quezon City in April, and two others in June (Rappler, April 15; Benar News, June 17).

In late June, IS released a video about current operations in the Philippines, part of a series about the global jihad. While much of the video was recycled, it is believed that the video was narrated by Sawadjaan, himself.

In July, Indonesian police arrested a member of the IS-linked Jamaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD), who was receiving funds and orders from a new Southeast Asian IS leader based in Khorasan Afghanistan. The previous month, Malaysian police arrested an Indonesian who was charged with further developing the logistics networks to get personnel in and out of the southern Philippines (Benar News, July 23).

The views reflect those of the author, and not the National War College or Department of Defense.