An In-Depth Profile of AQAP’s Qassim al-Raymi

An In-Depth Profile of AQAP’s Qassim al-Raymi

With the sharpened U.S. focus on combating global terrorism, closer knowledge of al-Qaeda’s branch in Yemen, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) — and, crucially, its leadership — is becoming increasingly more important. Before the U.S raid in Yemen in February 2017, which according to U.S intelligence officials had top AQAP leader Qassim al-Raymi as the main target, the mastermind had gone largely unmentioned in the mainstream media.

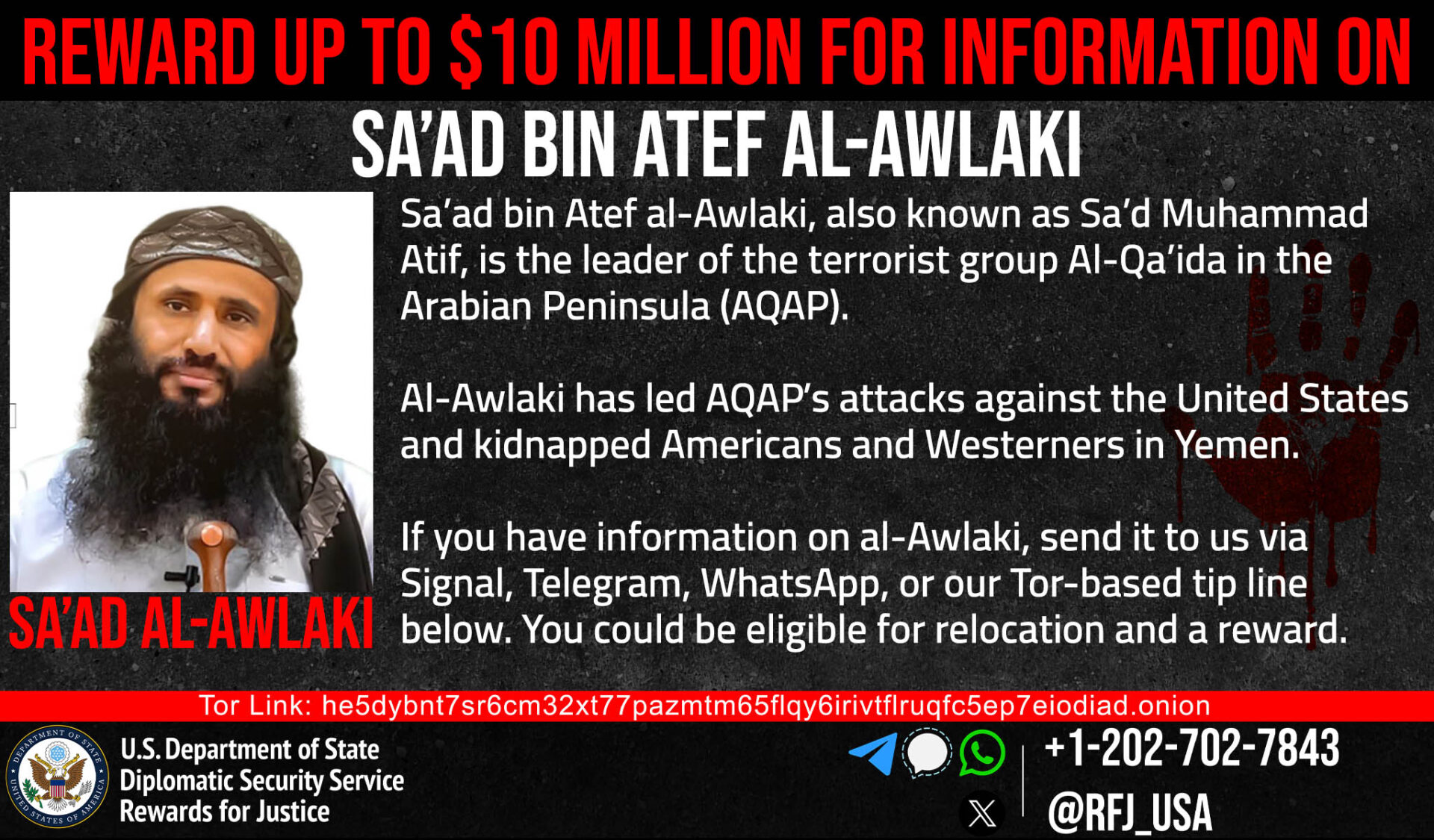

Though he has only recently started gaining wider attention, al-Raymi was first designated by the U.S. Department of State’s Reward for Justice Program as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist in May 2010, noting his senior role as an AQAP military commander, recruiter and trainer (Department of State, May 2010). A deeper examination of al-Raymi shows exactly what earned him this designation, revealing a charismatic man whose influence may establish him as one of the most dangerous terrorists in the world.

The Pistol Child

Qassim Abedah Mohammed Abkar al-Raymi was born on June 5, 1978 — some sources claim he was born in 1974 — in Yemen’s Raymah province, a mountainous region 200 kilometers southwest of Sana’a. The oldest of 12 siblings, al-Raymi grew up in a poor family, taking on fatherly roles early in life, because his father, a soldier in the Yemeni armed forces, spent weeks on end deployed to military installations (Department of State, May 2010; Monti Carlo Doualiya, June 16, 2015; al-Masdar Online, January 20, 2010).

Childhood friends remember him as tumultuous, chaotic and mischievous. Even before becoming involved in terrorism, descriptions of al-Raymi from those years capture an ominous, stubborn and hotheaded child with a pistol hanging from his belt at most times. This may have been al-Raymi’s first encounter with firearms, though surely not the last. As a teenager, in the early 1990s, without family consent or knowledge, al-Raymi vanished to points unknown (al-Masdar Online, January 20, 2010).

The 1990s were a ripe time for global jihad. Like other Arab jihadist volunteers, who came to be known as the Afghan Arabs mujahedeen (holy warriors), al-Raymi, as it turned out, had left home to join Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda Central (AQC) in Afghanistan, where he served as military trainer. While in Afghanistan, he linked up with fellow Yemeni Nassir Abdul Karim al-Waheshi, the late leader of AQAP.

Al-Raymi would return to Yemen in the early 2000s, following the U.S invasion of Afghanistan, only to be arrested by Yemeni security forces on charges of terrorism in 2005. However, a year later in 2006, al-Raymi, along with 23 detained AQ members including al-Waheshi, orchestrated a dazzling prison break in which forks were reportedly used to dig a tunnel to the nearest mosque (Rai al-Youm, June 16, 2015; Bawabatii, February 9).

Pre-AQAP Formative Experience

As the chief of military operations tasked with training and recruiting the next generation of AQ members in Yemen, al-Raymi is said to have orchestrated a number of attacks on Western targets in Yemen between 2006-2009, including: the car bombing of a group of Spanish tourists in the Ma’rib province in July 2007; an attack on Belgian tourists in Hadramawt province in January 2008; a mortar attack on the U.S. embassy in Sana’a in March 2008; and two suicide car bombs on the U.S. embassy in Sana’a in September 2008 (Bawabatii, February 9; al-Bawaba, July 2, 2007; al-Arabiya, January 18, 2008; al-Riyadh, September 18, 2008).

In January 2009, nearly three years after his prison escape, al-Raymi, alongside his mentor al-Waheshi, took a leading role in launching the AQ branch in Yemen— known formally as Tanzim Qaidat al-Jihad fi Jazeerat al-Arab (literally, Organization of Jihad’s Base in the Arabian Peninsula), best known as AQAP — by merging the Yemeni and Saudi AQ branches (Aden al-Ghed, June 16, 2015). AQAP, to be sure, is not the brainchild of these two; the group had existed in several variants since at least 1990, including as the Islamic Jihad in Yemen and al-Qaeda in Yemen (AQY), AQAP’s predecessor.

As al-Waheshi’s deputy, al-Raymi led AQAP’s military functions between 2009 and 2015, masterminding a number of global attacks (Bawabatii, February 9). Under his watch, AQAP claimed responsibility for the attempt to blow up a U.S.-bound commercial airline over the city of Detroit on Christmas day in 2009; the attempt to mail two packages containing bombs through UPS to synagogues in Chicago in October 2010; and the rampage at the Paris office of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in January 2015, which left 12 dead and several others wounded (al-Arabiya, January 10, 2015; al-Jazeera, December 28, 2009; BBC Arabic, October 30, 2010; al-Bawaba, November 5, 2010).

In Search of Popular Support

In June 2015, al-Raymi received the trust of AQAP Shura (Consultative) Council to become its top leader following the death of AQAP leader and AQ second-in-command Nassir al-Waheshi in a U.S drone strike in the coastal Yemeni city of Mukalla, in Hadramawt province (YouTube, June 16, 2016). Soon after, on July 10, 2015, al-Ramyi pledged allegiance to AQC leader Ayman al-Zawahiri (Assakina, July 11, 2015). Now that he is in full control of the group, the soft-spoken al-Ramyi took on the task of changing the popular image of AQAP from one that mostly draws on intimidation to one that largely appeals to local residents.

Within a few months of al-Raymi’s ascendance to top leadership, AQAP made several territorial gains in southern Yemen, where Sunni Muslims make up the majority of the local population. These included the capturing of the population centers of Ja’ar and Zanjibar, Abyan province, in December 2015 (YouTube, December 2, 2015; al-Quds al-Arabi, December 2, 2015); the recapturing of the commercial city of Azzan, Shabwah province, in February 2016 (YouTube, February 1, 2016; Rai al-Youm, February 1, 2016); and the retaking of several towns — Lawdar, Ahwar, and Shuqrah, Abyan province — in February 2017 (Sadapress.net, February 2).

AQAP’s territorial gains have been accompanied by two narratives. The first is that the group faced little local resistance. Given the embattled and dysfunctional Republic of Yemen Government (ROYG) and widespread violence across Yemen, locals appear to have little motivation to battle AQAP and risk retaliation. The second is that security, personal safety and service provisions have improved under AQAP governance. For example, in 2015, residents of Ja’ar city, Abyan province, explained that because of the lack of security and law enforcement, theft, bribery and nepotism had infested their local community under government rule. These conditions, residents said, changed under AQAP’s rule, as the terrorist group appeared to prioritize security and eliminate thuggish activities; provide consistent services, especially water and electricity; engage in mediating local disputes; and ensure swift justice (YouTube, April 12, 2015). Despite the harsh realities of living under enforced Sharia provisions, some residents found AQAP’s focus on addressing governance and the daily problems of the local population appealing.

AQAP also seems to have learned from experience, and thus is trying to win over locals by taking extra efforts to soften its image within its Sunni base of support. To this end, sparing civilian causalities and the destruction of cities has been the trend since al-Raymi assumed leadership. This likely has helped the group grow its popular support, and achieve its strategic objectives with less difficulty.

The following two examples illustrate how AQAP modified its strategy of almost total intimidation and compulsion into one that accommodates local concerns.

On November 29, 2015, and October 20, 2016, AQAP released statements defending its jihadist brand against the charges that its fighters unlawfully killed and wounded members of the Albu Bakr bin Diha sub-tribe of the al-Awalik tribe in the al-Dhala’ region, Shabwah province. Rather than ignoring the charges, AQAP asked the tribe to sit on a joint committee to investigate the matter. The committee concluded that shrapnel from an improvised explosive device (IED) that AQAP used against ROYG security forces had inadvertently killed the tribal members. AQAP then asked for the committee’s evidence be presented before a judge, in a religious court, for a definitive ruling. The court found AQAP guilty. AQAP accepted the verdict, formally apologized and compensated the families of dead and wounded accordingly. Throughout the process, the terror group was adamant about avoiding clashes with the locals by solving disputes through legal and peaceful means (Telegram, October 20, 2016).

Likewise, on April 25, 2016, AQAP released a statement explaining the circumstances involving its withdrawal from the city of Mukalla, Hadramawt province. Regional media outlets, such as the official Saudi Press Agency, reported that the Yemeni and UAE forces swiftly defeated AQAP, inflicting as many as 800 deaths (Saudi Press Agency, April 25, 2016. In fact, AQAP, aware of the offensive, simply withdrew on its terms toward the neighboring Shabwah province.

AQAP insisted the figure of 800 casualties was baseless, and that its losses could be “counted with the fingers on the hands” (Telegram, April 25, 2016). Moreover, the group said that the withdrawal decision was taken with local interests in mind, to spare the city bombardment and civilian causalities, after consultations with social and tribal figures in Mukalla. Media reports that emerged later on appear to corroborate AQAP claims (see Terrorism Monitor, October 14, 2016; Long War Journal, April 25, 2016).

The Far Enemy Is Never Far

Over the years, jihadist organizations, particularly AQC, have compartmentalized enemies into two categories — “far enemies” and “near enemies.” The former refers to Western nations and the United States, while the latter implicates apostate regimes in the Muslim world.

Al-Raymi appears to have moved away from this classification, noting that the far enemy is never really far. In a lecture published online, al-Raymi says that in the context of Yemen, the traditional cataloging of enemies would have the Yemeni government of President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi as the near enemy and the United States as the far enemy. The reality, however, al-Raymi asserts, is that the Yemeni government spends most of its time in Saudi Arabia, and its local security forces are too weak to present an immediate threat to AQAP. The United States, on the other hand, operates drones that fly only few miles above “our heads,” and is the most capable of inflicting damage. “Our leaders, like Abdu Rabbu [Mansour Hadi], is not the one attacking us — he is weak; it is the Americans,” al-Raymi concluded (YouTube, December 30, 2015).

This worldview matches that of Osama bin Laden, who saw Washington as the “head of the snake.” Likewise, al-Raymi, says that “if we want to kill an enemy, you would want to shoot him in the head, not in the leg. The leg is a secondary organ” (YouTube, December 30, 2015).

Also consistent with bin Laden’s worldviews is al-Raymi’s appreciation for a gradualist path toward establishing an Islamic caliphate, advocating for a measured imposition of Sharia law that would take into account local conditions, customs and nuances. He frequently criticizes Islamist groups — i.e. Islamic State — that prematurely declare a caliphate before having proper conditions and resources in place. “If you reap [unripe] fruit now, it is a waste of that fruit,” al-Raymi reasons (YouTube, December 30, 2015). Al-Raymi’s rationale for the unhurried declaration of an Islamic caliphate is that declaring it now would come at the expense of a more important issue — focusing the fight against the West and the United States, which all Islamist movements should join to defeat. “If each Islamist movement carries one operation per year against the United States, we would have been victorious by now,” he says (Marebpress.com, December 22, 2015; Akhbar al-Sa’aa, December 22, 2015; YouTube, December 30, 2015).

Looking Ahead at Security Conditions

With so much security and political disarray in Yemen, AQAP has been able to, and is likely continue to, build a sustainable presence in the country. It has been able to cater to the local Sunni population by providing basic services, and has made efforts to soften its image, which will likely help the group achieve its strategic goals with much less difficulty. AQAP’s leader Qassim al-Raymi has been key to recent successes, helping the terror group ascend from a small, barely known local group to one of the most talked about jihadist movements worldwide, and arguably the most successful AQ franchise.

A particular security challenge lying ahead is the evasive nature of al-Raymi — and, increasingly, his organization. Limiting exposure will likely be a key future AQAP tactic. It is clear that the group is increasingly adopting a more cautious military strategy through greater reliance on guerrilla hit-and-run tactics, ambushes, roadside bombs and rocket attacks. This tactical change is driven by al-Raymi. “It is a mistake to engage a stationary, well-positioned enemy face to face; we need to attack the enemy while it is on the move,” al-Ramyi said in an online lecture (YouTube, December 30, 2015). This shift will likely help inflict greater damage to AQAP’s adversaries while putting fewer of the terror group’s fighters at risk. Therefore, reliance on drone strikes and leadership decapitation is needed. This should come in concert to supporting the ROYG in building sustainable security forces while simultaneously working to improve governance and provision of basic service, countering AQAP’s soft approach.