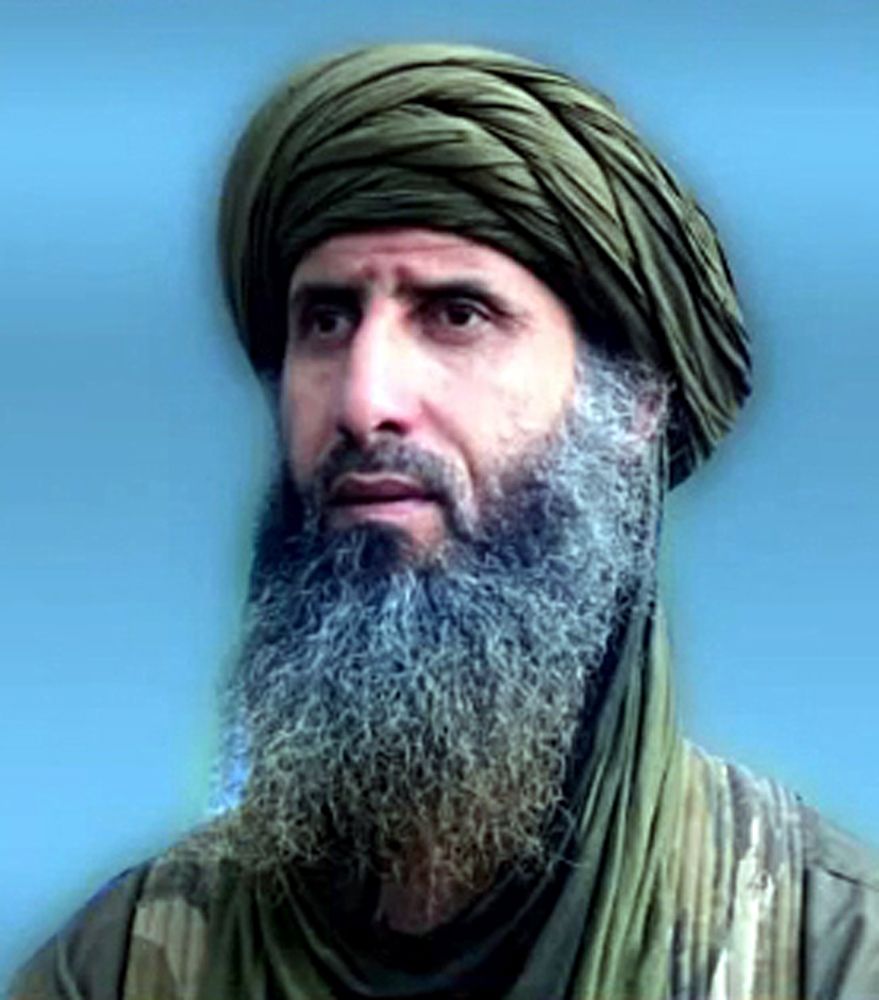

Abou Obeida Youssef al-Annabi: The Ideological Leader of AQIM

Abou Obeida Youssef al-Annabi: The Ideological Leader of AQIM

Abou Obeida Youssef al-Annabi, born on February 7, 1969, is the nom de guerre of Yazid Mebrak (Interpol, Feb 29, 2016). Al-Annabi is originally from Annaba, in the northeastern corner of Algeria near the border with Tunisia. Annaba is Algeria’s main port for mineral exports and the site of significant events in Algeria’s recent history, including the assassination of President Mohamed Boudiaf in June 1992 and the emergence of an obscure terrorist group called Midad El Souyouf in 2007. (Jeune Afrique, June 28, 2016; L’Expression, Jan 9, 2007).

The information publicly available on his life is scarce. He was a veteran of the Islamic Armed Group (GIA), which he joined in his early twenties. He later joined the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) when it emerged as a new movement following the split within the GIA. Al-Annabi remained with the movement as it became al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) between 2006 and 2007. In September 2015, he was designated a terrorist by the U.S. State Department (Huff Post Maghreb, Sept 10, 2015; Reporters.Dz, Sept 9, 2015; UN, Feb 29, 2016). In 2009, he was allegedly injured during an operation by Algerian security services near Tizi Ouzou (Ennahar, Nov 7, 2011).

By the end of 2011, al-Annabi became the head of the AQIM Shura, the leadership council of the organization. He is widely considered the group’s No.2 and the potential successor to AQIM’s emir, Abdelmalek Droukdel (Le360.ma, Sept 10, 2015). For years, however, particularly between 2010 and 2011, there were significant rumors that al-Annabi had actually replaced Droukdel as the head of the organization, but this proved to be inaccurate (France 24, July 26, 2010; La Liberté, April 14, 2010).

Matthieu Guidiere, terrorism expert and professor at the University of Paris 8, reports that al-Annabi holds the position of supreme authority over theological and legal matters in AQIM. As Guidiere says, “al-Annabi dictates the theological line, decides what is legitimate and what is not, and provides the ideological and doctrinal guidance of the organization” (Le Nouvel Observateur, May 7, 2013).

Indeed, over the past few years, he has proved to be the central figure in explaining the ideology of the organization. Having given some of the organization’s most critical speeches, al-Annabi seems to have risen to his leadership position due to his role as AQIM’s chief elaborator. This is in contrast to other members of the organization, such as Droukdel, who made this way through the ranks thanks to his technical skills as a bomb maker, or leaders like Mokhtar Belmokhtar or Abou Zeid – killed in 2013 – that were men of action and very involved not only in jihadist activities but also in the economic and trade activities – often illicit – flourishing in the Sahara (See TM Vol: 7 Issue: 12, 8 May, 2009).

The Ideological Centrality Within the Organization

Confirming the ideological importance of his role as the head of the AQIM Shura council, al-Annabi has released some of the organization’s most important speeches on topics well beyond local issues. For instance, he has given messages calling upon militants to fight the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria (Essalam/Djazairess, August 1, 2012). Al-Annabi was the protagonist of the messages entitled “The War on Mali” that Al Andalus Media Forum, the media branch of AQIM, broadcast on a number of jihadist forums on May 6, 2013 (Jihadology, May 7, 2013). The message was significant as it was released in the wake of Operation Serval, the French military operation that halted the advance of AQIM and its allies from moving further south in Mali. After taking control of the North, the organization attempted to establish an Islamic proto-state, years before the Islamic State (IS) would attempt the same thing. In addition, this operation not only destroyed the al-Qaeda-esque ambition to develop a Sharia-dominated state in Northern Mali, but also dismantled the well-established networks that AQIM had built there over the previous ten years, thus pushing the organization to reorganize itself (see TM, Vol.11, Issue 11, May 30, 2013).

In the message, al-Annabi attacked France for its specific role in dismantling the group’s achievements in Mali. The critique reflected a much more profound and long-lasting animosity toward “unbelievers.” Al-Annabi argues that religious hostility towards Islam is only one of the reasons why France intervened in Northern Mali. Other reasons include the historic and economic relationship France has with the country. Al-Annabi also points to the personal political concerns of French leaders, arguing thhat the then-President of France Francois Hollande needed to go to war in order to divert the focus of French public opinion from other, more pressing problems. Al-Annabi criticized the alleged double standards of Paris, accusing France of covering up the atrocities committed by the Malian army and the various African militias operating against the Muslim population in the north of the country. In the speech, he also provided a religious justification for the call to jihad in a Muslim land against a foreign enemy by releasing a specific fatwa, calling for total mobilization of Muslims against France and making jihad a personal obligation for every capable Muslim, supporting the “weakened brothers in northern Mali” without being discouraged by the French military superiority. For al-Annabi, those with the strongest faith and belief will win (the Muslims), thus urging Muslims to target French interests to drag it into an open and protracted war. (Jihadology, May 7, 2013; Le Nouvel Observateur, May 7, 2013).

His public speeches have often focused on external interference in the region. In the wake of the Arab Spring revolutions of 2011, al-Annabi attacked NATO for intervening in Libya. In the following years, he released other speeches concerning the situation in the country. He was particularly active in 2016, when, in a speech, he attacked the Skhirat agreement of December 2015, which brought together the two rival Libyan governments to support a new, national unity government. In the speech, made a few weeks after the agreement was reached, al-Annabi called it a “plot” supported by Western crusaders. At the end of the speech, he openly called for attacks against Italy, threatening the “the new invaders, the nephews of Graziani… You will bite your hands regretting that you entered the land of Omar al-Mukhtar and you will come out humiliated and submissive, with the permission of God” (La Repubblica, Jan 14, 2016; Ansa, Jan 14, 2016).

Al-Annabi’s cultural and historical references are not classic, jihadist and Islamic references. Instead, they are references very much embedded in the Libyan national history. For instance, he references Omar al-Mukhtar, the Libyan hero of the anti-Italian resistance. Al-Mukhtar was killed by the Italians, hanged in one of the concentration camps created by Rodolfo Graziani, the commander of Italian forces in Libya and vice-governor of Cyrenaica who, in the 1930s, ruthlessly crushed the Libyan resistance, earning the nickname “The Butcher of Fezzan” (Il Fatto Quotidiano, April 12, 2013). References like these were much more in line with the narratives that have often characterized the speeches of Muammar Qadhafi. However, they are vital, as they show the awareness of al-Annabi that, in order to strengthen the support for al-Qaeda in Libya, the group did not need to use words and images coming from its own ideological imagination. Instead, AQIM had to adapt to the specific conditions of Libya, as Libyans are known for being particularly keen on their national myths.

AQIM, in that period, was very focused on Libya, given that the challenge posed by IS in the country was becoming particularly significant. In addition, the group was under pressure from the United States, as showed by the American-led attack in June 2015 that claimed the life of Mokhtar Belmokhtar. In June 2016, AQIM posted another message, in which al-Annabi called on Libyans, referring again to them as the descendants of Omar al-Mukhtar, to join the fight against the Libyan army and the French forces in Benghazi (Libya Herald, June 26, 2016). Over the years, he has also focused on other issues having a significant symbolic value for Muslims and militants. For instance, back in early 2016, in the same message in which he threatened Italy, he also called openly for Ceuta and Melilla—cities in North Africa bordering Morocco—to be returned to the Muslim world (La Vanguardia, Jan 15, 2016).

Conclusion

Al-Annabi has a very peculiar profile within AQIM. He is apparently less focused on direct action than most of his peers. He obviously has a significant ideological and theological reputation within the organization, also given the formal role that he has held over the past few years. He has often been the protagonist of some of the organization’s essential public releases, dictating ideological and theological guidelines not only to militants but also to the broader Muslim community, as was the case in Mali in 2013. However, his history and ideology did not prevent him from exploring other ideological and historical backgrounds, as shown by his capacity to adapt the organization’s rhetoric, for instance in Libya. Omar al-Mukhtar was indeed a symbol of anti-colonial resistance, but he cannot be defined as an Islamic symbol at all as he is a national symbol of Libya.

Ideologically, one would expect AQIM to reject everything that is ‘national,’ given that modern nations, their identity and borders are the product of Western colonialism and imperialism. National borders produce Fitna within the Ummah and the Dar al-Islam. Despite this, al-Annabi used this reference to frame the fight of Libyans against the Italians and the French in the post-Qadhafi era. Many have often described al-Annabi as a potential successor to Droukdel. While his ideological and theological credentials for such a role are solid, he does not seem to be a man of action, unlike Droukdel and Belmokhtar. This could be a problem for him if, in the future, he aspires to become the leader of the organization.