Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s Growing War with North Yemen’s Houthist Movement

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s Growing War with North Yemen’s Houthist Movement

Relations between the Zaydi Shi’a Houthi rebels in Yemen and al-Qaeda have never been friendly, despite government claims to the contrary. The two movements have not yet had direct confrontation, focusing rather on their own conflicts with the Yemeni government. However, two al-Qaeda-claimed attacks in late November that targeted Houthi gatherings in northern Yemen have changed the situation between the two groups.

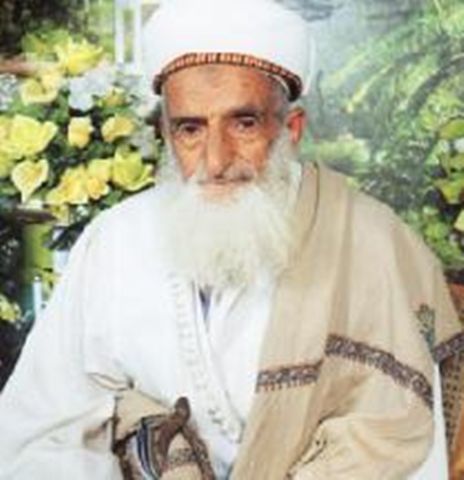

The first attack took place on November 24, 2010, in al-Jawf province. Twenty-three people were killed when a car bomb detonated in the middle of a crowded Houthi festival (Al-Hayat, November 24, 2010). The next day the Houthis issued a statement announcing the death of their spiritual leader, Badr al-Din al-Houthi. The cause of death of the 86-year-old man, according to the statement, was chronic asthma (Al-Hayat, November 25, 2010). On November 26 another car bomb hit a convoy of people headed to the funeral of Badr al-Din al-Houthi in Sa’ada, the stronghold of the rebels. Two were killed and eight injured in that second attack.

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) claimed responsibility for the attacks and also added that Badr al-Din al-Houthi was among the dead in the first car bombing in al-Jawf (Al-Fajr Media Center, December 3, 2010; Al-Quds al-Arabi , December 3, 2010). Nevertheless, Houthi spokesmen claimed the attacks were the work of American and Israeli intelligence agencies. The accusation was consistent with Houthi allegations that AQAP is directed by American interests, though it may also have been inspired by a desire to avoid open sectarian conflict or to avoid appearing as an American ally in the struggle against al-Qaeda.

AQAP’s first clear stance on the Houthi issue came after the Saudi involvement in the fight against the Houthis in late 2009. In an article written by AQAP deputy leader Sa’id al-Shihri in the AQAP on-line magazine Sada al-Malahim, Houthis were labeled rawafidh (rejectionists), a pejorative term AQAP commonly uses to describe the “Twelver Shi’a” of Iran, Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East. Zaydis are “Fiver Shi’a” and follow a form of Islam closer to local Shafi’i Sunni forms than to the Islam practiced in Iran (Sada al-Malahim, Issue 12, February 2010). Al-Shihri also accused the Houthis of being controlled by Iran and acting as part of an Iranian plan to dominate the Middle East (Aljazeeratalk.net, February 18, 2010).

Since 2004 the Houthis have survived six campaigns brought against them by the Yemeni army. Saudi forces intervened in the last one in late 2009, launching aerial and ground assaults against the Houthis whom they accused of crossing the Saudi borders (see Terrorism Monitor, January 28, 2010). The last round of fighting ended with a Qatari-mediated ceasefire which resulted in the Houthis keeping their arms and dominating the areas in and around Sa’ada.

Some suggested that the AQAP attacks were a reprisal for the abduction of AQAP operatives by Houthis who subsequently handed them over to the authorities. The field commander of the Houthis, Abd al-Malik al-Houthi, son of Badr al-Din, recently called for his followers to fight AQAP in the province of al-Jawf, an emerging battlefield for the confrontation (Al-Quds al-Arabi, December 3, 2010).

AQAP, however, described the operations in terms of a wider strategic prospective. In a statement published on pro-al-Qaeda web-sites, AQAP stated:

"Those operations came after the repeated call by the Sunnis for their brothers to defend them after the failure of the apostate governments of Sana’a and Riyadh to confront the Houthi Rawafidh (i.e. Shi’a); we launched those operations to defend the honor of Prophet Muhammad…. The Shi’a danger is coming [and] if the Sunnis do not face it properly the Rawafidh Shi’a will do to you what they did to the Sunnis in Iraqi and Afghanistan. The Saudi and Yemeni armies do not represent the Sunnis" (newpress.maktoobblog.com, November 29, 2010; al-Quds al-Arabi December 3, 2010).

The statement also revealed that AQAP had formed special units to defend the Sunni community and root out the Houthis, calling on people to join them.

Houthist field commander Abd al-Malik al-Houthi avoided giving any sign of intended retaliation. An all-out war between his group and AQAP would present a challenge of a different nature to his tough mountain fighters. They have displayed a great degree of sophistication in their guerilla tactics against the Yemeni army while operating in their strongholds in northern Yemen, but a confrontation with AQAP would force the Houthis to operate beyond their lines, as most AQAP strongholds are in the south.

On the other hand, AQAP has clearly penetrated the Houthis’ areas. Complicating this is the fact the Houthis are already involved in a conflict with Sunni tribes backed by the government. AQAP is urging those tribes to abandon the government and join them. However, the Houthis still have a strategic card to play in their relations with AQAP. Most of the roads crossing between Yemen and Saudi Arabia pass through areas of Houthis domination. AQAP would need to use those routes to operate effectively between the two neighboring countries.

The two attacks have created a strong challenge to the Yemeni government’s allegations that there was collaboration between AQAP and the Houthis in spite of their obvious sectarian differences (see Terrorism Monitor Briefs, September 17, 2009; Terrorism Monitor, November 19, 2009). The Saudi sources support the same theory. When prominent AQAP leader Abu Hareth Muhammad al-Awfi (a.k.a. Muhammad Atiq Awayd al-Harbi) turned himself in to Saudi authorities, he told the media that the main reason behind his decision was discovering that the “Iranian-linked” Houthis offered support for AQAP (Al-Arabia, October 17, 2010). As one of the four men who appeared in the video announcing the formation of AQAP, al-Awfi’s move was a major blow to the movement, though the Saudi presentation of his statement on the Houthis appeared to be an attempt to discredit the Houthist movement through association with AQAP.

Apart from a brief statement condemning the bombings and promising to chase the perpetrators, the reaction of the Yemeni government appeared unclear. It is obvious that Sana’a would not be sad to see a showdown between its two fierce enemies. Yet, there is a danger of giving an opportunity to AQAP to assume the mantle of the Sunnis’ defender if the sectarian conflict escalated. President Saleh is well-known for his skills in playing his internal opponents against each other. The Houthi-AQAP strife presents a challenge, or perhaps even an opportunity, for Salih’s political skills.

The tactic of using car bombs against the domestic civilian population was a new development, even in immensely violent Yemen (car bombs were previously used against the U.S. Embassy in Yemen in September 2008 and against housing for Yemeni security forces in July 2008). Car bombs targeting civilian gatherings could cause sectarian polarization within the Yemeni society. Nevertheless that does not seem very likely at this stage as the Houthis cannot extend their support beyond their loyal base into the wider Zaydi community, let alone the Sunni community. Yemen might not be on the brink of a sectarian war but the coming events in the Houthi-AQAP conflict will play a major role in deciding the balance of power and shaping the security scene in Yemen.