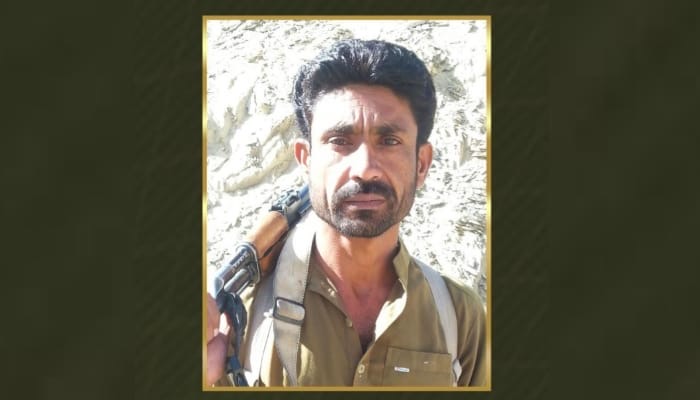

An In-Depth Portrait of a Pakistani Taliban Founding Father: Umar Khalid Khurasani

An In-Depth Portrait of a Pakistani Taliban Founding Father: Umar Khalid Khurasani

In August 2020, eight important Pakistani jihadist groups opposed to Islamabad joined the Pakistani Taliban, known as Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Among them was an influential group led by Commander Umar Khalid Khurasani, a.k.a. Abdul Wali Mohmand. The TTP chief, Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, declared that Khurasani’s return to TTP marked the beginning of a new era for the group (Umar Media, August 18, 2020). Khurasani has had quite an influential role in the rise of anti-state jihadism in Pakistan and is a founding figure within the TTP. [1] He is one of the most influential anti-state Pakistani jihadist commanders currently operating in the country.

Khurasani is the only TTP commander currently on the U.S. Reward for Justice list. The United States is offering $3.5 million for information that leads to his arrest or killing (Reward For Justice). All previous TTP commanders on this list have been killed in U.S. drone strikes. [2] Khurasani has survived multiple drone strikes and several raids conducted by U.S., Afghan and Pakistani forces. He remains an influential name among anti-state jihadists in Pakistan (The Express Tribune, October 16, 2017).

This article looks at Khurasani’s biography, which reveals crucial complexities in the jihadist landscape of Pakistan and its implications for Afghanistan’s security environment.

Pro-State to Anti-State Jihadism

Khurasani started his jihadist career from a state-loyal Pakistani jihadist group, Harakat-ul-Mujahideen (HuM) in 1996. [3] HuM was founded in the 1980s to support the Afghan jihadists in their fight against Soviet forces. [4] HuM quickly became an ally of the Afghan Taliban after its emergence, assisting in the group’s expansion by providing trained, devoted soldiers from Pakistan. Under HuM, Khurasani fought in Afghanistan in 2000 to defend the Taliban regime in Kabul. HuM and its members also became close to al-Qaeda during this period, which later influenced the group’s members. After 9/11, HuM fighters would go on to play a substantial role for al-Qaeda in Pakistan. [5]

Khurasani soon became a trusted subordinate to the HuM chief, Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman Khalil, who appointed him as the HuM emir of his native Mohmand tribal agency. [6] Khalil trusted Khurasani as his guide through the Tora Bora mountains in late 2001, where he headed for an important secret meeting with Bin Laden. [7] This was a crucial period for Osama Bin Laden and al-Qaeda, as the group fought for its survival while surrounded by U.S. forces and its Afghan allies.

Khurasani shifted his militant adventurism from Afghanistan to Kashmir after 9/11, where he was appointed to a HuM training camp, where he oversaw the group’s presence in the Pakistani side of Kashmir in 2003. [8] The Pakistani President, General Pervez Musharraf, initiated a peace process with India in the same year, which resulted in a ban on the jihadist groups based on the Pakistani side of Kashmir. [9] These jihadist organizations were already profoundly hurt by the state’s post-9/11 policies of supporting the United States in its Global War on Terrorism, which they considered to be a betrayal of their ideological brethren in Afghanistan. These Pakistani state restrictions on the Kashmiri jihadist groups further fueled their anger against the state.

Khurasani was one of the hundreds of jihadists—infuriated by the government tightening its policies toward the insurgents—who ended up in al-Qaeda-run training camps in Waziristan. [10] Al-Qaeda prepared these frustrated jihadists for its future war in Pakistan, which would eventually lead to the creation of TTP.

Founding Role in TTP

Khurasani spent only a few months in Waziristan, taking part in attacks against U.S.-allied forces in the neighboring Afghan province of Paktia and fostering new relationships with other militants. He befriended the TTP’s future founder, Bait Ullah Mehsud, and joined his network, called the ‘Bait Ullah Mehsud Caravan.’ This was a small group of Bait Ullah loyalists, limited in reach to South Waziristan, who provided shelter to al-Qaeda and its jihadist allies and participated in attacks against U.S.-allied forces in Afghanistan. Khurasani pledged allegiance to Bait Ullah, who appointed him to the position of emir, responsible for his native Mohmand agency, where he was once responsible for HuM operations as that group’s local leader. [11] Along with carrying out a career as an insurgent, Khurasani also worked as a journalist for a national Pakistani newspaper in his native Mohmand agency (Dawn, February 8, 2015).

Unlike other, short-term thinking TTP commanders, Khurasani established that he had broad, long-term goals for fighting in Pakistan, including by taking the fight beyond the tribal belt. This is evident by his founding role in establishing a countrywide united jihadist front, which later emerged as the TTP organization. Khurasani was the first person to suggest that the Bait Ullah Mehsud Caravan should be expanded to all of the tribal areas and into other Pakistani provinces to establish a strong front against the state. [12]

For this purpose, he first convinced jihadist commanders from the areas neighboring Mohmand, including Bajaur, Swat, Buner, and Malakand areas, to join the group. Khurasani then sent a delegation to other tribal agencies to meet with various jihadist groups, convincing them to join a united jihadist organization. In these meetings, Khurasani suggested that Bait Ullah be the leader of the umbrella organization. All these efforts ultimately resulted in the establishment of TTP at the end of December 2007 in Waziristan (Umar Media, 2012).

A central point of the new TTP organization’s guidelines to local commanders was to stop the activities of jihadist insurgent groups that were in support of the Pakistani state and not allow any such group to join TTP. [13] Following these instructions, Khurasani eliminated a major Salafist-jihadist group that was using Mohmand agency as a staging ground to operate in the neighboring province of Kunar, Afghanistan against U.S.-allied forces (The Express Tribune, September 21, 2010). Tensions between Khurasani and the Salafist-jihadists resulted in significant challenges for the jihadist leader later in his career.

Bait Ullah’s successor, Hakeem Ullah Mehsud, appointed Khurasani as TTP’s emir of Khyber agency in 2012, which was the strongest jihadist stronghold after Waziristan. Ansar-ul-Islam (AI), a strong pro-state militant group, existed in the strategically important Tirah valley of Khyber agency, presenting the TTP and its anti-state allies with several challenges (Dawn, January 28, 2013). The first thing Khurasani did after becoming Khyber emir was eliminate the AI from the Tirah valley, with support from TTP groups from neighboring Orakzai, Dir, Bajaur, and Waziristan areas (The News International, March 19, 2013).

Khurasani went on from this success to become a formidable TTP commander after two of his close aides were given critical roles in TTP’s central leadership. His former spokesman, Ehsanullah Ehsan, was appointed as TTP’s Central spokesman and his deputy, Qari Shakeel Ahmad, became leader of the both the TTP executive council and political commission. [14] This made Khurasani a significant leadership figure in TTP, placing him as a serious candidate to succeed Hakeem Ullah in late 2013. That Khurasani was not chosen to lead the organization would partially result in his splintering from TTP.

Parting Ways With TTP

Khurasani always held major ambitions for TTP. He aimed to develop its organizational structure like that of the Afghan Taliban, transitioning the group from a fluid alliance to a strong, centralized insurgent force. The TTP was based around a tribal structure, where each tribal unit was nearly independent and central leadership held minimal control of its regional wings. Khurasani had convinced some TTP senior commanders, including Hakeem Ullah, of the need for these reforms, but it never materialized. At that time, the strongest TTP subgroup, TTP Mehsud, led by Mufti Wali ur Rehman, was against any such reforms, and would not allow any external interference in his group, including from the TTP emir. [15]

Khurasani’s frustration with the TTP leadership structure further increased when Fazlullah appointed him to oversee Mehsud tribal relations, for the purpose of controlling fighting between two major TTP Mehsud factions, the Khalid Sajna group and Shehryar Mehsud, who were loyalists of Wali ur Rehman and Hakeem Ullah, respectively. The Sajna group opposed Khurasani’s appointment, declaring that Fazlullah was ignorant to think that he could control the powerful Mehsud Taliban faction through an outsider commander. [16]

The second incident that further deepened Khurasani’s division with the TTP leadership was his opposition to negotiations with the Pakistani government. Islamabad had offered to open peace negotiations with TTP shortly before the assassination of Hakeem Ullah. The majority of the group’s commanders favored negotiating (Dawn, May 23, 2013). Khurasani doubted that the government would follow through with the TTP’s demands, including implementing Sharia law and ending Pakistan’s alliance with the United States. According to him, the negotiations were a trap, meant to harm the TTP’s unity (Umar Media, 2014). Khurasani covertly carried out major, brutal terrorist attacks in the country to damage the peace negotiations. The attacks were later claimed by two unknown groups, Ahrar-ul-Hind and Abna-ul-Hafsa (Dawn, July 26, 2014; Dawn, September 7, 2014).

Becoming the TTP leader was the only way for Khurasani to run the group according to his own ambitions. This made him a serious candidate for TTP leadership when Hakeem Ullah was assassinated in a U.S. drone strike in November 2013 (Geo News, May 12, 2017). The subsequent appointment of Fazlullah as the leader of TTP and his subsequent policy choices further weakened the TTP organizational structure, finally resulting in Khurasani splintering from the group. He was succeeded by several other important commanders, while he himself established a separate faction in August 2014, known as Jumat-ul-Ahrar (JuA) (Ihay-e-Khelafat, August 2014).

Khurasani’s Inclinations Toward Islamic State Khorasan

Khurasani was thought of as a likely candidate to join Islamic State Khorasan (IS-K) branch because he shares similarly radical beliefs and is closely associated with IS-K’s founding figures—who were formerly influential TTP commanders—including Shaikh Maqbool Orakzai and Hafiz Saeed Khan. Secondly, Khurasani always tied his operational goals with the eventual establishment of a Caliphate, which Islamic State (IS) declared globally. That declaration was the reason that he authored several articles in JuA’s magazine, titled Ihya-e-Caliphate [revival of the Caliphate], which welcomed the arrival of the IS caliphate. [17] Khurasani stated in his essays that the IS declaration of a Caliphate was a major victory for jihadists across the globe.

On the other hand, Khurasani was still despised by some of the Afghanistan-Pakistan area Salafists for his role in eliminating the pro-state Salafist-jihadist group in his native Mohmand agency shortly after establishing TTP in 2008 (The News, July 18, 2008). Khurasani always claimed that his conflict with Shah Khalid was a result of his close collaboration with the Pakistani security establishment, which created issues for Khurasani and TTP. Khurasani has stated that his conflict with Khalid was not rooted in his Salafist-Hanafist sectarian beliefs. [18] Despite his clarifications, the Shah Khalid group accused him of being anti-Salafist due to his actions against their group. That same group of Salafists quickly came to dominate IS-K and shaped it into a pure Salafist group. These IS-K figures included the former Shah Khalid loyalist, Shaikh Jalaluddin, who served as a top religious figure in the group (Jihadology, September 2015). This was one of the main reasons that Khurasani’s path into IS-K was blocked, despite his ideological commitment and past operational successes.

Conclusion

As Khurasani rejoins TTP, his major issues with the organization’s central leadership now seem resolved, particularly that of structural reforms. The September 2018 TTP guidelines issued by the group’s current leader, Mufi Noor Wali Mehsud, addressed this issue (Umar Media, 2018). This could be the reason that Khurasani, in a recent interview with TTP Umar Radio recorded after he rejoined the organization, gave listeners his unconditional apologies for all of his past mistakes and suggested that all other TTP commanders do the same (Umar Media, August 21, 2020). He emphasized that this is the time for all of the militant groups under the TTP umbrella to forget the past and unite for their future survival.

A TTP source based in Kunar, Afghanistan and close to Khurasani told the author that last year the Afghan Taliban issued a special code of conduct for interactions with anti-state Pakistani militants, including TTP [19]. This alarmed TTP splinter groups, instigating a return to unity for fear of their survival, as a decision by the Afghan Taliban to target the insurgents who are fighting their Pakistani sponsors could prove disastrous for those groups. The TTP source said that this fear resulted in Khurasani’s unconditional merger back into TTP. Khurasani admits in his interview with Umar Radio that secret negotiations to bring JuA back into the TTP umbrella had been going on for the past couple of years (Umar Media, August 21, 2020).

The expected change in the political and security landscape of Afghanistan as a result of the withdrawal of U.S. troops leaves TTP as the second largest militant group in the country behind the Afghan Taliban, thus posing a serious security threat to Pakistan. This makes influential anti-state commanders in TTP, like Khurasani, particularly dangerous actors.

Notes

[1] Umar Khalid Khurasani, “The Future of the Pakistani Army and Kashmir,” Ihay-e-Khelafat, Issue 1, April 2017, pp. 7-8.

[2] Those TTP commanders who were killed by drone strikes while listed on the U.S. Reward for Justice program include Bait Ullah Mehsud, Qari Hussain Mehsud, Hakeem Ullah Mehsud, Wali ur Rehman Mehsud, Khalid Said Sajna, Mullah Fazlullah and others.

[3] Ihya-e-Khelafat interview with Umar Khalid Khurasani,” Ihya-e-Khelafat, September 2013, pp. 6-11.

[4] HuM was a major Pakistani Deobandi jihadist group, established in the 1980s to support the jihadists war against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, later extending its operations into Indian Kashmir in the early 1990s. HuM also fought shoulder-to-shoulder with al-Qaeda and other foreign jihadists to help the Taliban keep its hold on Afghanistan since its emergence there in the mid-1990s. For details check, Muhammad Amir Rana, 2003. “Gateway to Terrorism,” (New Millennium publications: London).

[5] For details check, Don Rassler, “Al-Qaida and the Pakistani Harakat Movement: Reflections and Questions about the pre-2001 Period,” Perspectives on Terrorism, Volume 11, Issue 6.

[6] Khurasani, 2017.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Muhammad Amir Rana, 2015. “The Militant: Development of a Jihadi Character in Pakistan,” (The Narratives Publications: Islamabad).

[10] Khurasani, 2017.

[11] Other prominent jihadists who rose in the ranks of TTP and al-Qaeda in Pakistan and declares the same grievance as a central factor in turning against the state include, for example, Commander Badr Mansur, Engr Ihsan Aziz,Commander Khattab Mansur, and Mufti Asim Umar.

[12] Maulana Qasim Khurasani, “From the independence movement to the movement of Taliban in Pakistan,” Ihaye Khelafat, April 2017, pp. 13-14

[13] Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, Inqilab-i-Mehsud [Mehsuds Revolution] (Paktika, Afghanistan: Al-Shahab Publishers, 2017).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Umar Khalid Khurasani, “Seekers of the Islamic Caliphate,” Ihaye Khelafat, November 2014, pp. 12-14.

[18] “Ihya-e-Khelafat interview with Umar Khalid Khurasani,” Ihya-e-Khelafat, September 2013, pp. 6-11.

[19] This code of conduct from Afghan Taliban to TTP surfaced on social media in September 2020 (Twitter.com/Natsecjeff, September 13, 2020). A source close to TTP leadership in Kunar told the author that the Afghan Taliban handed these instructions to TTP quite earlier than the day they emerged online. The new rules stated that the TTP would have to register its members with the Afghan Taliban, and promise not to stage operations on foreign countries, such as Pakistan, from Afghanistan.

The TTP strongly protested the new rules to the Afghan Taliban, declaring that it undermines the critical role that TTP has played in the Afghan Taliban’s two-decade-long resistance against the United States and its allies in the region. Although the Afghan Taliban has not publicly commented on the new code of conduct rules, it alarmed various TTP splinter groups, pushing them to unite to survive in the future.