The Belt and Road Initiative: Is China Putting Its Money Where its Mouth Is?

The Belt and Road Initiative: Is China Putting Its Money Where its Mouth Is?

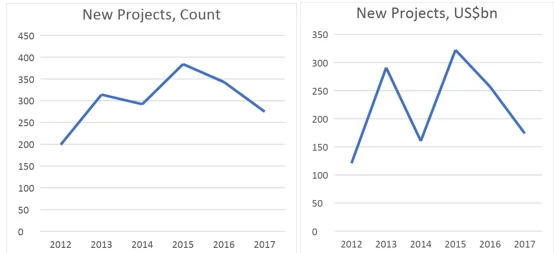

Five years after it entered discussions surrounding China’s foreign policy, the Belt and Road Initiative remains a subject of political priority and public attention. Beijing has recently made a habit of attempting to persuade visiting heads of state to offer formal endorsement of the initiative, as Emmanuel Macron, Theresa May, and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte have all found. Major international banks, among them Standard Chartered and Deutsche Bank, have signed on to Belt and Road-themed programs, while public attention towards the initiative continues to grow after a May 2017 spike. [1] Against this backdrop, it seems only natural that new project openings and capital commitments should continue on an upward trajectory. However, data collected by RWR Advisory Group shows that new projects in infrastructure, power, and energy—the lifeblood of the Belt and Road Initiative—have declined every year after peaking in 2015, measured both in terms of number of new projects and dollar amounts spent. [2]

Source: RWR Data

There are several possible explanations for this observed decline in outbound investment:

- The central government is pursuing meaningful curbs on capital flight. A secondary and not unwelcome consequence of the curbs may be a cutting of some of the chaff surrounding Belt and Road investment.

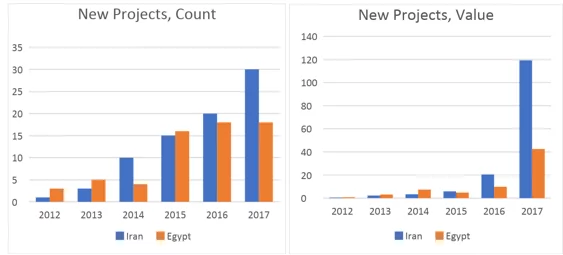

- What appears in aggregate to be a decline in capital intensiveness may actually represent a development of geographical refinement. Data from the same time period shows a continuation of the upward trend in a number of countries, such as Iran and Egypt.

- While Belt and Road is widely seen as a whole-of-country initiative, it could be that a select group of companies (SOE or private) have been handpicked to drive related projects forward.

- Aggregate data may also be hiding evidence of a more refined approach to the question of what Belt and Road is, in addition to where it is. This means that project openings in the infrastructure and energy sectors may be continuing to grow, despite overall activity showing a downturn.

- The Xi Administration has made ambitious strides in presenting China as a global power. But the proliferation of Belt and Road is such that it has become a bureaucratic meme. The downturn of new project announcements may merely be the result of the end of a cycle in a boom-and-bust policymaking environment.

- Lastly and quite simply, is not enough for projects to be announced—they must also be built.

While the Chinese economy does conform to a state capitalist model, it is unlikely that the government can guide the extent of the Belt and Road Initiative merely via indicating preferences and priorities. While the uptick in Iran and Egypt is likely the result of Chinese corporations taking the signal offered by Xi’s state visits to those countries, this is only an indirect means of setting the initiative’s trammels. Instead, capital controls and outbound investment review processes, as laid out by new NDRC rules and existing SAFE regulations, offer a much more tangible means of cutting the chaff from the Belt and Road Initiative. The lack of significant industrial concentration and the failure of Belt and Road “national champions” to emerge supports the analysis that the decline is the result of a tamping-down on superfluous investment, rather than the indication of discrete targeting. However, the NDRC regulations do strengthen the state’s ability to dictate what kind of outbound investment it wants, and what kind it does not want. Although the data does not yet show this, years to come may see a clearer emergence of targeting. In that sense, the decline shows an attempt to rein in a runaway policy. The next phase will be to (re)define what Belt and Road should look like.

Reining in Capital Outflows

Throughout 2017, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) led a regulatory drive to restrict outbound investment presented as targeting “irrational” investments by private conglomerates such as HNA, Wanda, and Anbang (State Council, August 4, 2017). But the unfolding of the Belt and Road Initiative has not been immune from high risk and dubious rationality. The International Monetary Fund’s October 2017 analysis that Chinese loans have put Zambia at risk of debt distress is a sign of the former, while mention of a “Digital Silk Road” points towards the latter (IMF, October 10, 2017; China Daily, December 4, 2017). A leaner, more targeted portfolio of Belt and Road projects would be a welcome consequence from controls on capital outflows. Indeed, the NDRC investment guidelines made this clear: investments that further the Belt and Road framework are explicitly encouraged.

But encouragement does not mean that a reversal of the overall downward trend should be expected. The focus across the Chinese bureaucracy on finding ways to control unwanted investment, paired with efforts to deleverage across the state-owned and private sectors, suggests that even though the NDRC rules do back Belt and Road investment, projects marketed as BRI-relevant will not receive carte blanche. Such a relaxation of control would simply be too abrupt. Instead, the goal remains a leaner and more targeted BRI. Cutting the chaff also means a greener BRI. Restrictions on investments that contravene environmental standards, contained within the NDRC document, show a growing sensitivity towards the need to maintain a positive reputation for Chinese projects overseas (State Council, August 4, 2017).

Regional Refinement

Tied to the notion of a leaner BRI is a refinement of where projects are opened and money is committed. While most major recipient countries saw a downturn in Belt and Road activity after 2016, Iran and Egypt both saw a major growth in overall new projects, not just those related to infrastructure, energy, and power. Both countries saw surges in investment after 2016 visits by Xi Jinping (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2016). In Iran’s case, these include a July 2017 $2.5 billion loan agreement between the Export-Import Bank of China to Islamic Republic Railways for an electrification project covering the 900km Tehran-Mashhad railway, as well as a $544 million railway construction contract agreed in January 2018 by China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation and Iran’s Construction and Development of Transportation Infrastructure Company (MEHR News Agency, July 25, 2017; China Railway Construction Corporation, January 4, 2018). In Egypt, China has become the largest investor in the Suez Canal Corridor, including a joint Suez Economic Trade and Cooperation Zone (Xinhua, March 3, 2017). Separately, China Harbor Engineering Company is set to begin construction this year of a $10 billion high-speed rail artery linking Aswan, Cairo, and Alexandria (My Salaam, December 1, 2017). If we understand the Belt and Road Initiative as a way for China to incentivize close political relationships around the world, both Iran and Egypt make sound strategic sense, particularly within the context of China’s drive to solidify its energy security. Iran is strategically located along one side of the Persian Gulf and is China’s fourth-largest source for crude oil imports, while Egypt’s Suez Canal is a chokepoint for Chinese trade into the Mediterranean and beyond.

Source: RWR Data

The Chosen Few?

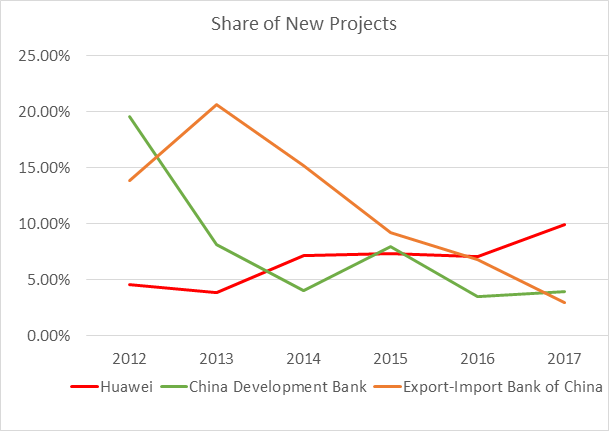

While there does seem to have been some refinement in terms of where Belt and Road projects are taking place, a whittling-down of contracting companies has not accompanied the decline in new projects. China Development Bank (CDB) has maintained a position of prominence throughout the period surveyed, while the Export-Import Bank of China, which fills a similar role, has seen its share of new projects decline, implying that CDB has become the preferred lender for projects in the developing world. But these are providers of finance, rather than contractors like Huawei, which saw its involvement in the overall share of BRI projects fall from 19.5% of new projects in 2012 to only 3.9% in 2017.

Source: RWR Data

This suggests that rather than selecting a handful of companies to be developed as Belt and Road “national champions”, companies—both state-owned and private—are engaged in a competitive process to identify and initiate new projects that fit within the Belt and Road paradigm. Indeed, since 2016, no contracting company has won more than 4% of total projects for the year in question. Interestingly, Huawei had the most projects of any non-financial entity in any of the years surveyed, but their share has declined substantially since the highs of 2012.

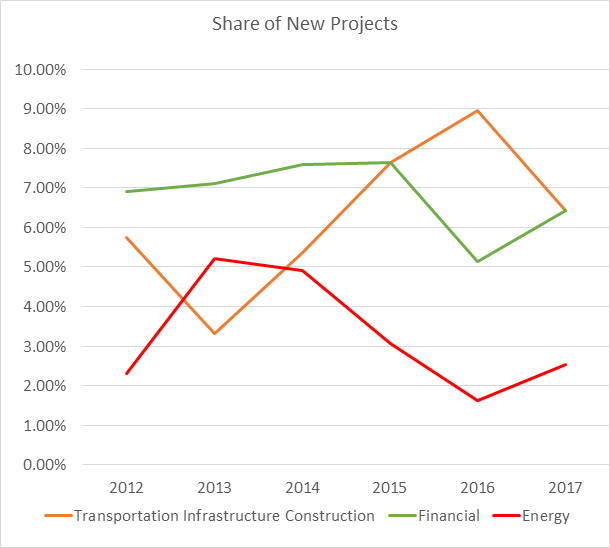

Greater Sectoral Focus?

As RWR’s data shows, industrial concentration between 2012 and 2017 highlighted the bread and butter of Belt and Road: transport infrastructure construction, and finance. But in 2018 year to date figures, finance-related projects rank only fourth in 2018, supporting the earlier suggestion that the Belt and Road Initiative has entered a less capital-intensive second phase. Transport infrastructure construction projects still rank in first place, but only occupy 6.7% of overall outbound activity.

Source: RWR Data

Other industries are on the rise within the context of overall Chinese outbound activity: real estate construction has occupied a greater share of total projects in every year since 2015, despite government attempts to curb real estate-related capital flight. But while there is growth in some sectors, there is scant evidence for any refinement in terms of the nature of China’s outbound activity. This aligns with the lack of an emergence of Belt and Road “national champions”. In both cases, it is possible that this is representative of a bottom-up competition for the political favor that is associated with Belt and Road. But pairing the lack of contractor or industry refinement does not square with the overall downturn in new projects since 2015: if there was a competitive process underway, it would be expected to lead to a rise in new projects, rather than a fall. Instead, the Belt and Road Initiative may be finding itself on the falling side of a boom-and-bust policy cycle.

From Project Announcement to Project Construction

Building transport infrastructure takes time, even before the proverbial first brick is laid. In the case of the 350km Belgrade-Budapest high-speed railway project, construction of the segment between Belgrade and the Serbian-Hungarian border only began in 2017, four years after the project was first announced, and the same year that was initially targeted for completion (Government of Serbia, December 16, 2014). Work is not scheduled to commence on the section between the border and Budapest until 2020 (Budapest Business Journal, October 4, 2017). Under such circumstances, it would be surprising if the project is completed inside ten years of the initial announcement. Cases like this are common in infrastructure construction. While high levels of new project announcements bolster the soft power dimensions of the Belt and Road Initiative by building a head of public and policy attention, projects must be completed to have their fullest and most tangible effect—not only in rebalancing supply chains but also in maximizing associated soft power growth. In that sense, the years between 2013 and 2015 showed a dedication to getting the Belt and Road Initiative off the launch pad. Five years after Xi’s Kazakhstan speech, it may simply be that initiative is entering a second phase that sees the emphasis move from announcing projects to giving the chronically under-defined Belt and Road Initiative a more tangible form.

Shifting Attention?

The Belt and Road Initiative maintains a position of pride within the Chinese policy lexicon. This much was underlined at the recently completed Two Sessions, where the National People’s Congress voted to establish an International Development Cooperation Agency, which will “allow aid to fully play its important role in great power diplomacy… and will better serve the building of ‘Belt and Road’”, according to State Councillor Wang Yong. However, it is far from the only focus. Reforms to the constitution and consolidation of Xi’s position pull rank in terms of media coverage, while the anti-corruption campaign and drive to de-leverage China’s companies occupy the mind of the bureaucracy. Overseas, other issues are driving China’s relationship with the wider world. These range from restrictions on Chinese investment to concern about China’s influence operations. Driven by a dynamic of competitive appeasement within Chinese bureaucracy and business, BRI seemed primus inter pares among Chinese policy initiatives. Now, however, BRI is at minimum moving to a less capital-intensive second phase. Understood in the context of the curbs on capital outflows, it is undergoing a course correction. Seen against political and policy developments associated with the 19th Party Congress, it is readjusting to sharing the spotlight. The Belt and Road Initiative is here to stay—at least as represented by the highways and railways that remain under construction—but it is entering a new reality that will not see unending growth.

Conclusion

It is clear that new projects have declined, whether measured by project value or announcement count. The reasons for the decline are less clear. It is overly simplistic to point to contracting companies and financers that were occupied with getting the Belt and Road Initiative off the ground have now moved their focus to actual construction work. Instead, a more compelling rationale is that regulators in Beijing are attempting to cut the chaff from outbound investment overall, and that the Belt and Road Initiative forms a subset of the target material. Evidence of a leaner BRI comes from greater regional specificity, namely a steep rise for new projects in Egypt and Iran. While there is a strong strategic motivation for amplifying China’s presence in both of these countries, the evidence does not point to a clear refinement in industrial concentration or the emergence Belt and Road “national champions” tasked with undertaking relevant projects. Indeed, while tighter capital controls and the pursuit of a leaner BRI do have good explanatory power, it should be remembered that the attention of Beijing policymakers may have been diverted by issues such as the anti-corruption campaign and the drive to de-leverage. This is not the death of Belt and Road, but the combination of tighter capital controls and competition for attention will result in a leaner BRI. Whether this results in greater definition of what BRI is remains to be seen.

Johan van de Ven is Senior Analyst at RWR Advisory Group, a Washington, DC-based risk management firm where he focuses on geopolitical dimensions of China’s international economic activity. Prior to RWR, he worked in policy consulting in Beijing. You can follow him on Twitter @Johanv91. The views expressed herein do not represent those of RWR Advisory Group.

Notes

[1] As approximated by related Google searches. [2] RWR Advisory Group leverages open-source information to compile and maintain a database of outbound economy activity propagated by Chinese state-owned and private enterprises. For more information, please visit www.rwradvisory.com