Chinese COVID-19 Misinformation A Year Later

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 2

By:

Introduction

On January 28, members of an international team led by the World Health Organization (WHO) concluded fourteen days of quarantine and began field work in Wuhan, China for a mission aimed at investigating the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of the time of writing, the team had made visits to the Hubei Center for Disease Control and Prevention; the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) and the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market. State media also reported that the WHO team visited “an exhibition featuring Chinese people fighting the epidemic,” raising concerns that the trip could prove to be little more than a public relations move even as the origins of the coronavirus remain heavily politicized and uncertain (Global Times, January 31). Foreign experts have worried about whether the WHO investigation will be sufficiently transparent or if investigators will be allowed adequate access to key locations and scientific data (SCMP, January 27). Apart from a “terms of reference” report and a list of WHO members released in November, further details on the WHO team’s trip have not been released.[1]

The WHO team’s research was politicized by an international debate over COVID-19’s origins even before it began work. Last year, U.S. government officials repeatedly gave credence to a so-called “lab leak hypothesis” culminating in the State Department’s release of a Fact Sheet on January 15, which gave previously undisclosed evidence for “illnesses inside the Wuhan Institute of Virology” and warned that “the CCP’s [Chinese Communist Party] deadly obsession with secrecy and control comes at the expense of public health in China and around the world (U.S. State Department, January 15). On the other side, officials and state media in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have spread theories aimed at muddying the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic and countering criticisms of an official narrative that China’s response to the pandemic has been “open, transparent, and responsible” from the beginning.

Obfuscating the Origins of COVID-19

The Chinese state’s misinformation regarding the origins of COVID-19 can be dated to the last week of February 2020, when the respiratory expert Zhong Nanshan (钟南山) told state media that although “COVID-19 was first discovered in China, it does not mean that it originated in China” (Xinhua, February 27, 2020). By early March, spokespersons for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs were repeating this notion during daily press briefings, and the notorious “wolf-warrior” diplomat Zhao Lijian (赵立坚) shared a conspiracy theory via his personal Twitter account claiming that the U.S. Army had brought COVID-19 to Wuhan during the October 2019 Military World Games (PRC MFA, March 4, 2020; Zhao Lijian via Twitter, March 12, 2020). China analyst David Gitter has characterized China’s early efforts to obfuscate the origins of COVID-19 as a kind of opportunism aimed primarily at protecting the Chinese government’s reputation during a national catastrophe and characterized the CCP’s directing of blame abroad as being part of an established propaganda toolkit.[2]

In May, an article in the CCP’s leading theoretical journal warned readers that the “political virus” (政治病毒, zhengzhi bingdu) of anti-China rhetoric—to include efforts to tie the coronavirus’ origins to Wuhan—was “more dangerous” than COVID-19 itself (Qiushi, May 18, 2020). A white paper published in June represented perhaps the clearest effort by state authorities to “shape and control the narratives” surrounding China’s response to the pandemic, but provided insufficient evidence to clarify the coronavirus’ origins (PRC National Health Commission, June 8, 2020; China Brief, June 24, 2020). The ambiguity has led to ongoing confusion over China’s COVID-19 response. In a recent response to two interim reports presented at the WHO’s executive board meeting which appeared to gently criticize both China and the WHO’s early responses to the pandemic, a Chinese representative complained that the timelines of China’s response laid out in the reports were “inconsistent with the facts” and called on the authors to “further improve the reports and make scientific, objective, fair, comprehensive and balanced assessments.” But the dates in the reports were confirmed both by the WHO and by the June white paper (SCMP, January 20).

The WHO team’s long-delayed investigation into the origins of COVID-19 in Wuhan has renewed close scrutiny of China’s early missteps in containing and managing the virus. China’s international reputation has undoubtedly suffered in the wake of the pandemic, and official propaganda appears to have had difficulty in bridging the gap between domestic and foreign audiences (China Brief, December 6, 2020). Ongoing efforts by government officials and the state media apparatus to promote theories about the multiple origins of the coronavirus and suggest its transmissibility via frozen food packaging (ie. the cold chain hypothesis) demonstrate the continued political utility of COVID-19 misinformation.

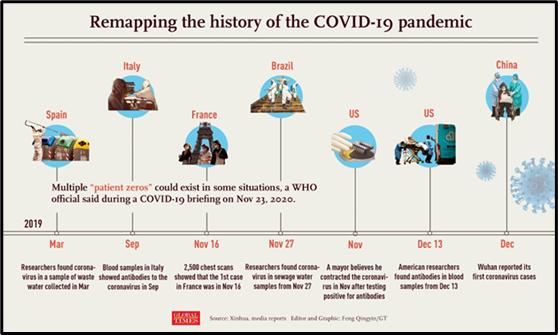

Multiple Origins

As already mentioned, Chinese officials and state media attempted to divert inquiries into COVID-19’s origins away from Wuhan as early as March (Xinhua, March 22, 2020). Often relying on foreign media reports or citing international epidemiologists, state media promoted research that appeared to show the virus’s origins in Italy, the Netherlands, France, Australia, India or Spain—anywhere, basically, but Wuhan (Global Times, June 27, 2020; Deccan Herald, November 29, 2020). In one instance, Chinese media reports selectively cited quotes from German biochemist Alexander Kekulé to claim that “the starting point of the pandemic is not in Wuhan,” but instead attributable to a northern Italy variant (China Daily, December 1, 2020; CGTN, December 5, 2020). When asked about this claim, Kekulé said that his words had been twisted out of context and denied the Chinese media reports as “pure propaganda” (Hindustan Times, December 14, 2020).

On January 2 State Councilor and Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi (王毅) summarized a triumphal version of China’s fight against the coronavirus, saying “We race[d] against time and report[ed] the epidemic to the world first. More and more studies have shown that the epidemic is likely to be an outbreak in many places around the world” (Xinhua, January 2). When asked whether it was China’s official position that the virus began outside of China during a press briefing on January 18, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying (华春莹) replied, “COVID-19 broke out in multiple places around the world in the autumn of 2019…it is not only China’s narrative, but a fact, a common objective narrative of many countries” (PRC MFA, January 18). During the same briefing, Hua appeared to use China’s cooperation with the WHO as an opportunity to engage in a strange form of whataboutism while doubling down on the multiple origins theory, saying, “I’d like to stress that if the United States truly respects facts, it should…invite WHO experts to conduct origin-tracing in the United States” (PRC MFA, January 18). A subsequent article in the Global Times echoed this rhetoric, asking: “When will the U.S. invite experts of the WHO or other international institutions to investigate the origin of COVID-19 in the U.S.?” (Global Times, January 22).

One of the issues that reportedly delayed negotiations over the WHO probe into the origins of COVID-19 was Beijing’s determination to accept such an investigation only if it was not country-specific.[3] WHO experts have had to walk a fine line in order to maintain access to China. In November, Michael Ryan, Executive Director of the WHO Health Emergencies Program, said that it would be “highly speculative for us to say that the disease did not emerge in China” (Channel News Asia, November 28, 2020). In January, a member of the WHO team in Wuhan told CGTN, “I don’t think we should rule out anything [about the virus’s origins]. But it is important to start in Wuhan, where a big outbreak occurred” (CGTN, January 11).

Cold-Chain Hypothesis

Following a June coronavirus outbreak in Beijing that was linked to imported foods, Chinese regulators nationwide devoted significant efforts to testing samples of imported food from “high-risk countries” (SCMP, June 19, 2020). In recent months, the state tabloid Global Times has published a number of reports suggesting evidence that imported cold-chain food products were the source of outbreaks from port cities to inner provinces such as Heibei and Heilongjiang where recent outbreaks have surfaced (Global Times, October 27, 2020; November 29, 2020, December 6, 2020). These media reports have caused widespread concern among Chinese consumers and led authorities to announce enhanced testing for imported fruits and vegetables, meat, and ice cream (Sixth Tone, October 27, 2020; Global Times, January 26).

Other countries have ruled out cold storage as a vector for transmission and complained that Chinese delays on importing food have caused significant trade disruptions (ABC News (Australia), August 18, 2020). Foreign experts have repeatedly argued that while the virus can survive for a time on packaging, the actual likelihood of transmissibility across cold chain imports is very small.[4] China has rejected these criticisms and said that it is putting people’s lives first in the fight against the coronavirus (PRC MFA, November 18, 2020).

Conclusion

Once again, it appears that in the face of constant and consistent pressure from China, the WHO may be contemplating a revision of its official guidelines, which have so far maintained that cold chain transmissions of coronavirus do not represent a strong risk. Draft advice leaked from the WHO earlier this year appeared to warn that the virus could spread via the cold chain (Wall Street Journal, January 22).

Throughout 2020 and into the new year, Chinese officials and state media repeatedly perpetuated claims about the multiple origins of COVID-19 and its transmissibility through cold-chain imports, which have been repeatedly questioned or debunked by foreign experts. These state-driven conspiracy theories contrast sharply with ongoing efforts to control information related to the pandemic. The Chinese state charged and prosecuted more than 17,000 people in connection with “disseminating false information about the pandemic on the Internet” last year (Beijing News, January 10). And an investigation by the Associated Press, published in December, has found that the central government has tightly controlled publication of academic research into the coronavirus’ origins (AP, December 30, 2020). Even as China cracked down on COVID-19-related censorship domestically, it has continued to perpetuate misinformation both at home and abroad in an attempt to avert blame for its role in the origins of the coronavirus pandemic.

Notes

[1] Foreign experts have criticized the terms of reference, which allowed Chinese scientists to do the first phase of research absent international oversight. See: “WHO-convened Global Study of the Origins of SARS-CoV-2: Terms of References for the China Part,” November 5, 2020, World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-convened-global-study-of-the-origins-of-sars-cov-2.

[2] See: David Gitter, “A Great Test: The CCP’s Domestic Propaganda Campaign to Defend Its Early COVID-19 Fight,” in Party Watch Annual Report 2020: COVID-19 and Chinese Communist Party Resilience, Center for Advanced China Research, January 24, 2021, pp. 36, https://www.ccpwatch.org/annual-report.

[3] See: Emily Rauhala and Lily Kuo, “Politics frustrate WHO mission to search for origins of coronavirus in China,” The Washington Post, January 6, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/coronavirus-china-wuhan-who-visit/2021/01/06/f880d41c-48bf-11eb-97b6-4eb9f72ff46b_story.html.

[4] See: “Explainer: China’s claims of coronavirus on frozen food,” November 24, 2020, Associated Press, https://apnews.com/article/pandemics-beijing-global-trade-coronavirus-pandemic-china-28671d69256d84001a471876a6bc4077.

Elizabeth Chen is the editor of China Brief. For any comments, queries, or submissions, feel free to reach out to her at: cbeditor@jamestown.org.