Chinese Growing Social Inequality Prompts Stronger Social Control

Chinese Growing Social Inequality Prompts Stronger Social Control

In China, growing social inequality and popular frustration with the lack of means of legal redress are being met with a combination of crackdowns and government social campaigns. Domestically, these dual efforts are costing the central government, as it trades effort for stability. The recent arrest and forced confession of several legal activists in China have highlighted growing pressure on civil society groups (People’s Daily Online, January 20). Chinese President Xi Jinping has also increased the Chinese state’s emphasis on ideological education and public morality, the latter background to an intensive anti-corruption campaign which has netted thousands of corrupt officials. Many observers initially believed that Xi’s confrontational tactics were necessary to breakup vested interests standing in the way of economic reforms needed to address rising income inequality. However, as of early 2016 there are no clear signs that Xi has a plan for such reforms, or that the vested interests have been vanquished. Moreover, despite renewed promises by Xi and other top Chinese leaders that the government will end poverty by 2020, a potential “social volcano” which gave rise to an enormous emphasis on maintaining order, and gave rise to the massively expensive “wei-wen” or social stability (维稳) policies under Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao continues to loom.

The Basis of a Social Volcano is not Simple Inequality

The possibility of social unrest due to inequality is also of keen interest to those trying to assess the country’s stability. A call for discussion of the wealth gap was the single biggest demand of a 2015 online survey in the lead up to the meetings of the National People’s Congress and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (两会), though this amounted to only eight percent of respondents (Xinhua, April 29, 2015). A similar poll in 2015 by the Pew Center poll put the figure much higher at 33 percent. [1] Yet increasing numbers of Chinese do blame the administrative and legal systems for the problems so many have when seeking redress for serious problems and solving issues of state-sanctioned inequality. They are very unhappy with rampant inequality in the system. As a result, if crackdowns on civil society are seen together with his positive ones, such as his emphasis on combatting corruption, improving the legal system and access to government, key elements of procedural fairness, all of which come under his slogan “the four comprehensives” (四个全面), then there is a hitherto unrecognized coherence and significance to his policies and priorities. Behind many of the so-called mass incidents that led to the wei-wen policies are issues of corruption, arbitrary confiscation of land, lack of say into the location of potentially environmentally disastrous factories such as PX chemical plants and, increasingly, environmental issues more generally (China Brief, December 21, 2015). [2]

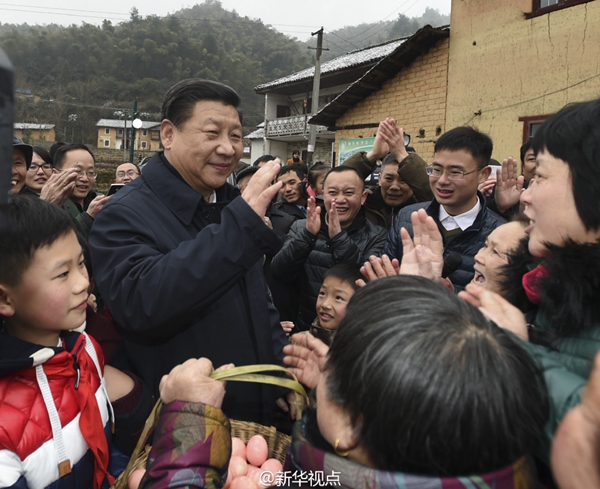

Contained within the four comprehensives, is the possibility that Xi and those around him have grasped this more pressing threat than that attributed to inequality per s, and also helps explain the patterns of repression we are witnessing. The substantial work of Martin K. Whyte and his colleagues has shown that the dramatic growth of inequality, is not the source of popular resentment that many imagined. Whyte’s 2010 The Myth of the Social Volcano, makes it clear that despite public awareness of the growing inequality, at the individual level, blame is directed inwards and blamed on personal lack of ability or education, rather than attributed to the system or the CCP. [3] However, the Chinese central government has made poverty relief a hallmark of its policies in rural areas. Policy is coordinated through the State Council-level Leading Group on Poverty Alleviation (扶贫开发领导小组) led by Vice-Premier Wang Yang. Xi Jinping has made poverty a key issue, pledging to meet the 2020 goal of lifting China’s rural poor out of extreme poverty, a group that as of 2014 included 70 million Chinese citizens (Xinhua, November 3). This group has been largely left behind by China’s economic success which has been largely concentrated in the cities. Rural governments are often under-funded, and unable to provide basic security and social services (China Brief, September 4).

While this finding is very important as it seems to let the Party-state off for systemic failures and its legitimacy is not threatened as a result of this issue, many people are increasingly unhappy about another endemic problem: systemic procedural unfairness and the problems of gaining redress for injustice. [4]

What is notable about the considerable efforts underway to repress those individuals, groups and systems is that they are overwhelmingly involved in dealing with the problems created by absence or failure of systems which ought to deliver procedural fairness. Labor unions, labor and human rights lawyers, NGOs, public interest and lawyers are all key avenues through which those who fail in their bids to seek redress for wrongs through government departments and the legal system, seek to publicize their cases and receive compensation. When such individuals and groups work with lawyers and bloggers to raise issues both at home and abroad they both emphasize CCP institutional failings and so tarnish the CCP’s claims to always be acting in the interests of the people. This dramatic illustration of failures is no longer tolerable, and helps explain the ramped up censorship and control of the media. Any substantial solution will alleviate the need of the aggrieved to publicly air grievances, go to activist lawyers, or engage with NGOs which often need to politicize particular issues to gain attention, redress or more work. By default, suppression of civil society channels means that official channels will become even more important but failure to make them more effective will only compound public unhappiness.

The Four Comprehensives

Xi’s flagship anti-corruption campaign has a significant, though largely unspoken, element of reducing rent seeking, including from those seeking redress through official channels or who seek redress because they have been subject to corruption or its consequence, such as forcible confiscation of land. Success in this area alone should help improve fairness considerably. Yet Xi has also simultaneously promoted reviews of the petitioning (信访) system and emphasized the need to develop the legal system (法制) to cope better with solving grievances, win popular trust and build legitimacy.

However, it was Xi’s February 2015 announcement of the four comprehensives in February 2015, in advance of the lianghui (两会), the annual pair of meetings of the National People’s Congress and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference which brings together these and many other mooted reforms which, if implemented effectively and before problems reach crisis point, would make China a much fairer place and allow many problems to be resolved speedily and justly. First announced in 2014 then relaunched in 2015, the four measures are:

- Comprehensively build a moderately prosperous society (全面建成小康社会).

- Comprehensively deepen reforms (全面深化改革).

- Comprehensively implement the rule of law (全面依法治国).

- Comprehensively strictly govern the Party (全面从严治党).

Xi links achieving a prosperous society with a less iniquitous one, but also recognizes that continued economic development is crucial for maintaining employment levels and increasing incomes. Continued reform is crucial to allow the achievement of prosperity. Governing the nation according to law is the most important for addressing the chronic problems of procedural unfairness. This becomes much clearer in Xi’s writings on developing the legal system as expressed in his 2014 book, The Governance of China. Three short pieces in the book, most notably “Promote Social Fairness and Justice, Ensure a Happy life for the People” emphasize both raising the credibility of the legal system and developing a system which they get to trust the law as an instrument that not only protects social stability but also protects their interests, together with a Confucian overlay of promoting virtue. [5] The protection of peoples’ lives and property is crucial. Although the wording does not make it clear that the most powerful threat to such property is arbitrary confiscation by elements of his own Party-state, Xi’s repeated calls for wiping out judicial corruption and ensuring upright servants of the law does hint at this. The fourth comprehensive, strict governance of the Party itself, is yet another attempt to ensure virtuous behavior by all Party members and officials without the need to create new institutions which make being good more normal and desirable. In short, Xi seems to be calling for a Singaporean-type system where citizens have great trust in the bureaucracy and law but in which both systems nevertheless actively support continued one-party rule.

Intensifying United Front Work and Avoiding Political Crises

Another, much less well known organ active in understanding the problems of key minorities is the CCP’s own United Front Work Department (UFWD; 统一战线工作部), which expanded suddenly by some 40,000 cadres in 2012. The significance of this expansion and Xi’s subsequent endorsements of the department in July 2015, is that the UFWD investigates the concerns and interests of many key groups, and seeks to bring influential representatives from them in-line to publicly support Party policies. Among the underappreciated reasons that this is a significant move, and one seemingly underway from the time of Hu Jintao, is that united front work has proven itself highly useful each time the CCP has faced major problems of transition or when handling crises. This was the case during the transition to socialism in the early 1950s, the aftermath of the disastrous Great Leap Forward (Famine) of 1959–1961, the pivot away from Maoism especially the reinstitution of markets after 1976, and in the aftermath of the killings and suppression of the student movement of 1989. [6]

Over the last five or ten years, the UFWD has also increasingly concentrated on investigating and seeking to coopt the many new interest groups emerging as a result of China’s economic success and increasing global integration. Among these, new capitalists, independent professionals particularly lawyers, the post 1978 wave of Chinese migrants around the world etc. In 2015 Xi effectively boosted the status of the Department and further extended its targets to include internet celebrities and Chinese students studying abroad. All of these groups can become important sources of protests against the CCP if alienated and the UFWD seeks to understand their grievances, address them where possible, and then represent them in in large through the National People’s Congress systems but particularly in the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) which is the ultimate representation of CCP cross class legitimacy. However, both bodies have also become more effective at investigating issues and formulating new laws and policies in the national (and Party) interest and trying to solve problems before they become critical and anti-Party. United front work has often meant having to address issues of procedural unfairness that give rise to political discontent among crucial interest groups, even if finding the right CCP cadres to do such sensitive work, particularly with religious believers and ethnic minorities, continues to be a problem. That there have not been great crises yet is one indication of the success of the Department’s work.

Conclusion

It is not clear whether the picture outlined above is in fact as consciously planned as overarching policy as implied here, or merely the coming together of disparate measures, but there is a substantial coherency if each is seen as being at least in part, efforts to improve procedural fairness and transparency throughout. China’s leaders have demonstrated cognizance of the need to make significant progress with the comprehensives in the context of a slowing economy. While unrest about inequality has so far been muted, this is because most ordinary Chinese, like people everywhere, generally compare themselves to family, neighbors and those in similar situations and for most people most of the time, things have been getting better. An economic slowdown, however, will bring inequality and particularly procedural unfairness into much sharper relief. Worse, real setbacks and losses, such as declining property prices, will immediately result in a mass sense of relative deprivation and bottled up grievances are likely to boil over. Xi and the Party leadership are seemingly aware of these problems. The pressing need for reform coexists with increasing suppression of non-state reformist groups and civil society. Unfortunately, considering how much easier it is to squash complaints about unfairness and jail those seeking to make the Party and society aware of them, it is almost certain that the necessary complementary reforms will fail to be appropriate, complete or effective enough.

Gerry Groot is Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies and Head of the Department of Asian Studies at the University of Adelaide, South Australia. He has writes on united front work, soft power, social change as it relates to China and Asian influences on Western culture past and present.

Notes

1. Richard Wike and Bridgit Parker, “Corruption, Pollution, Inequality are Top Concerns in China, Pew Research Center, September 2015.

2. H. Christoph Steinhardt and Fengshi Wu, “In the Name of the Public: Environmental Protest and the Changing Landscape of Popular Contention in China,” China Journal, Issue 75, January 2016, pp. 61–82.

3. Martin K. Whyte, The Myth of the Social Volcano: Perceptions of Inequality and Distributive Injustice in Contemporary China, Stanford University Press, 2010.

4. Martin K. Whyte, “China’s Dormant and Active Social Volcanoes,” China Journal, vol. 75. 2016, pp. 9–37.

5. Xi Jinping, The Governance of China, The Foreign Languages Press, Beijing 2014, pp. 149–170.

6. Gerry Groot, (2004) Managing Transitions: The Chinese Communist Party, United Front Work, Corporatism and Hegemony (Taylor & Francis, New York).