Dreams Deferred in Xi’s New Year’s Speech

Dreams Deferred in Xi’s New Year’s Speech

Executive Summary:

- Xi Jinping’s New Year’s speech hinted at weaknesses in the People’s Republic of China.

- The speech emphasized the many hardships that people are currently facing at home while acknowledging fears about a turbulent external environment.

- Xi did not mention “national rejuvenation” and he conceded that the “China dream” was far from being realized.

- Doubling down on the ideology of struggle, a hard work ethic, and enforcing nationalist sentiment as crucial factors for escaping the current malaise, Xi’s speech suggested a shortage of tangible solutions for the country’s problems.

January is a busy month for the central government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). It provides a short period to review the previous year, set the agenda for the year ahead, and prepare for the annual “two sessions” meetings of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) in March, before the Spring Festival holiday at the end of the month. The announcement on January 17 that the economy met its 2024 growth target of “around 5 percent” represents part of this effort (Xinhua, January 17).

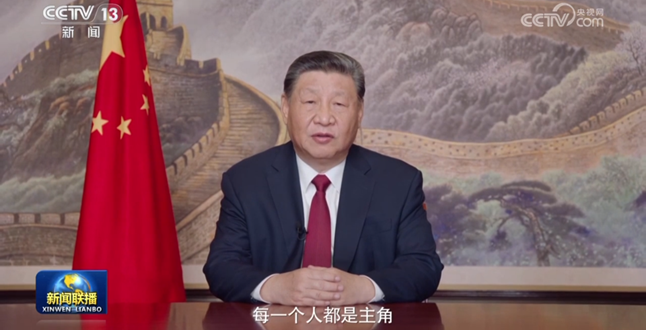

In the “new era” under President Xi Jinping, the year always begins on December 31 with a televised address broadcast on CCTV-1, the country’s main state television channel (MFA, December 31, 2024). The speech follows a general format that has remained consistent throughout Xi’s time in office. Running for just over ten minutes, it featured Xi sitting behind a large, wooden desk with artwork depicting the Great Wall as his backdrop. In it, the president addresses highlights from the past year and looks ahead to upcoming one, with the video of him speaking to camera frequently interspersed with clips from around the country.

As an annual phenomenon, Xi’s new year’s speech provides a useful benchmark that can provide insight into how the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) perceives their performance. While the content is mostly pro forma, any changes in terms of structure, additions, emphasis, or omission may suggest changes in Xi’s outlook. Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, Xi’s rhetoric has become more candid, occasionally acknowledging some of the difficulties and challenges people are facing. Another trend is increasing emphasis on international affairs. In earlier years, this was relegated to brief references commemorating the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, which have since disappeared (China Brief, January 5, 2024).

Unusual Speech Suggests Weaknesses

This year’s speech contained several notable differences from previous iterations. For the first time since 2017, and only the second time since he began making these speeches, Xi’s was not seated in his office. As a result, no bookcases could be seen in the background, and so no information could be gleaned from the titles or the pictures that are often carefully selected for display over his shoulder, the salience of which are often painstakingly detailed in propaganda materials for those who don’t take the hint (People’s Daily App, January 1, 2020; CGTN, December 31, 2023). Also absent this year are the phone sets, the calendar, and the stationery that traditionally sit atop the desk. In another contrast, this year’s speech was slightly shorter in length, and the camera appeared to cut away from Xi with more regularity.

Clear conclusions are difficult to draw from this choreography but, given the attention to detail that accompanies every carefully scripted Party ritual, these changes matter. A comparison with the other outlier, the 2017 speech, provides some clues (Xinhua, December 31, 2016). In 2017, Xi strode into the hall, gripped the podium with both hands, and stared down the camera to deliver his speech, exuding confidence as he declared significant breakthroughs in military reforms and world-beating achievements in other domains. This year, Xi cuts a much more isolated figure, no longer surrounded by family photos, unable to pick up the phone. One can speculate that this might represent Xi’s increasing isolation at the top of the Party, though it is not possible to assess this with any degree of confidence.

The content of the speech itself also contains valuable hints as to the leadership’s perspectives on the current moment. Back in 2017, Xi sold the Chinese people on a utopian promise: “There is no such thing as a free lunch,” he said, “but by exerting yourself through struggle, dreams can come true (天上不会掉馅饼,努力奋斗才能梦想成真).” While this year’s speech noted that “countless workers, builders, and entrepreneurs are striving to fulfill their dreams … (无数劳动者、建设者、创业者,都在为梦想拼搏 …),” toward the end of his remarks Xi gave a more concise and conciliatory version of this 2017 statement. “Dreams may be far away, but if you pursue them, they can be achieved (梦虽遥,追则能达).”

The admission that the “China dream (中国梦)” is still a long way off is an unusual moment of candor, not least for where it arrives in the speech (China Brief, September 25, 2014). The moment comes at the start of the final segment before Xi’s signoff, directly after noting “changes unseen in a century (世界百年变局)” and as a segue into discussing the road to “Chinese modernization (中国式现代化),” two slogans that define Xi’s diagnosis of and prognosis for world affairs perhaps more than any others. While this placement is noteworthy, the omission of Xi’s lodestar, the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation (中华民族伟大复兴)” is even more unusual, as it is a concept that has often been closely connected to the China Dream and a mainstay of previous speeches (UDN, January 1; YouTube/VOA, January 4).

One possibility for these changes could be that Xi has one eye on the international audience. As the PRC moves into 2025, its export-driven economy is increasingly reliant on maintaining favorable relations with countries around the world. As such, many of Xi’s remarks had an international focus. He described the PRC as a “responsible major country (负责任大国)” in a “turbulent world (世界变乱交织)” that has “actively promoted changes in global governance and deepened solidarity and cooperation in the global South (积极推动全球治理变革,深化全球南方团结合作)” and has “put a lot of positive energy into maintaining world peace and stability (为维护世界和平稳定注入更多正能量).” The “responsible major country” reference is a pointed critique of the United States, which it sees as a destabilizing force, as is the clip shown of a medal ceremony from the Paris Olympics in the summer, in which the PRC flag is raised above that of its rival.

Another possibility is that the economic situation at home really is causing reassessment. Xi makes frequent references to this throughout the speech. He claims that he “has been concerned about issues such as employment and income, the need for families to care simultaneously for both the old and the young, as well education and medical issues (对大家关心的就业增收、‘一老一小’、教育医疗等问题,我一直挂念).” He also warns that the economy “is facing some new circumstances, there is the challenge of uncertainty in the external environment and pressure of transformation from old growth drivers into new one (运行面临一些新情况,有外部环境不确定性的挑战,有新旧动能转换的压力).” These are clear signals that he acknowledges domestic issues, and are echoed by remarks made to the CPPCC tea party the same day, where he warned that Chinese modernization would entail “not only clear skies and gentle breezes but also fierce storms and even turbulent waves (不仅有风和日丽,也会有疾风骤雨甚至惊涛骇浪)” (People’s Daily, January 1).

The solutions he offers are also concerning and support the view that his dreams—and those of the Chinese people—may have to be deferred. In his speech, he turns to work ethic and nationalism to rally support for the year ahead. He exhorts people to be confident, arguing that “we get stronger through hard times (我们 … 在历经考验中壮大).” At one point, he uses a graphic metaphor, proclaiming that the word “China (中国)” is engraved at the bottom of the “hezun (何尊)” (an ancient bronze vessel that contains the earliest known reference to “中国”), but “even more so in the hearts of every Chinese child (更铭刻在每个华夏儿女心中).” What is left unspoken is that the party-state’s repressive apparatus—currently on high alert—will coerce those who do not wish to “eat bitterness (吃苦)” (People’s Daily, May 28, 2023; China Brief, December 6, 2024).

Conclusion

Xi’s conviction that the people must be willing to suffer and struggle to achieve his ambitions has been made clear beyond his new year’s speech. At the plenary session of the Central Committee for Discipline Inspection the following week, Xi warned that “corruption is the greatest threat facing our Party, and the anti-corruption campaign is the most thorough form of self-revolution (腐败是我们党面临的最大威胁,反腐败是最彻底的自我革命)” (People’s Daily, January 7). The communique that came out of the session also noted that the anti-corruption struggle “is still severe and complex (仍然严峻复杂),” and an accompanying commentary called for cadres to be tough on themselves (自身硬) (People’s Daily, January 9; (People’s Daily, January 10). It was also articulated in a speech published in Qiushi, the Party’s theory journal, on New Year’s Eve. The speech, which was given to top Party, state, and military leaders in February 2023, includes a section about “the necessity of advancing with great struggle (必须进行伟大斗争)” in order to achieve national rejuvenation (Qiushi, December 31, 2024).

The new year holds great uncertainty for the PRC. Politically, Xi has reengaged with his most important international interlocutor, President Donald Trump (Lianhe Zaobao, January 17). The incoming administration’s decisions will have a decisive impact on the PRC’s trajectory. Economically, Xi will hope that the economic plans set out between the Third Plenum in July 2024 and the Central Economic Work Conference in December will start to bear fruit. Ultimately, this could be the year that Xi Jinping comes to know whether his dreams will have to be deferred momentarily, or if they will be derailed altogether.