Georgian-Chinese FTA: A Trade Agreement With Caveats

Georgian-Chinese FTA: A Trade Agreement With Caveats

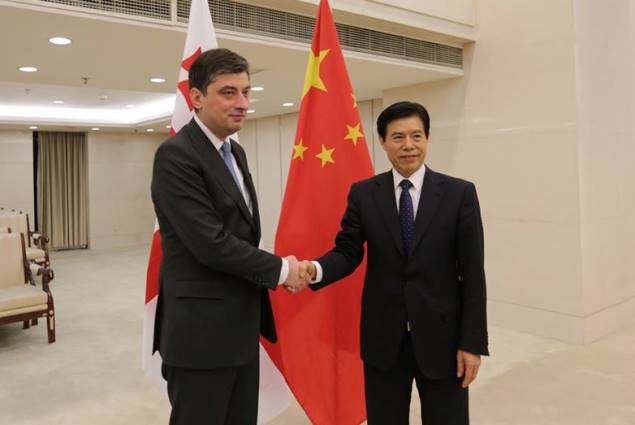

When the Minister of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Zhong Shan and Georgia’s Minister of Economy Giorgi Gakharia signed a bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in Shanghai, on May 13, it all looked good on paper. Following a seven-month-long process of final-stage negotiations, which culminated in the signing, the Georgian government was quick to announce that the FTA—China’s second such deal with any country in Eurasia, after Switzerland—opens the world’s largest market of about 1.4 billion consumers to Georgian goods. Ninety-four percent of Georgian exports to China will now be tax free (Amerikiskhma.com, May 16). “Georgia has a steadily growing export to China. We see a great potential in concluding free trade agreements with big economies such as China,” Gakharia noted. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili enthused about “moving towards a higher level of cooperation” (Civil Georgia, May 14).

It is true that the PRC is now the third most important destination for Georgian exports, after Russia and Turkey, according to data from January–March 2017. Moreover, China already occupies the fourth position—after Turkey, Russia and Azerbaijan—in imports. Indeed, Georgian exports to China increased sevenfold from $25.7 million in 2012 to $169.6 million in 2016, with Chinese imports—at their highest point in 2014 at about $733 million—dropping to $547.5 million in 2016 (Amerikiskhma.com, May 16). However, this dynamic demonstrates a persistent negative foreign trade balance between the countries in recent years, which in 2016 still stood at 52.7 percent in China’s favor (Commersant.ge, May 17). Likewise, between January and May of 2017, Georgia sent $82.3 million in exports to China and took in $226 million of Chinese imports, thus continuing the significant trade deficit trend, equaling 45.6 percent to the detriment of the Georgian side (Geostat.ge, June 26).

Economist Gia Khukhashvili believes that due to the sharply unequal economic development of the two countries, the Georgian-Chinese FTA will, in fact, likely exacerbate the pre-existing, large import-export gap (Commersant.ge, May 17). This is even though China represents the second-largest market in the world for a crucial Georgian agricultural export—wine (Amerikiskhma.com, May 16). “We do not have the same quantity of export products as China,” Khukhashvili stressed. “Hence an expansion of Chinese products [in Georgia] is inevitable.” Furthermore, the FTA will displace potential direct investments in Georgia’s real economy: more inexpensive Chinese products could drive out competing investors, who may lose interest in Georgia due to Chinese low prices. Thus, the real economy will fail to further develop, Khukhashvili warned, noting that the vast majority of European countries do not have FTAs with China specifically because of this possibility. Yet, the Georgian government has dismissed the possible negative consequences, and for the foreseeable future it is preferencing liberalizing trade with China over its direct investments in local production.

Most experts can only point to potential future benefits from the FTA for Georgia, be they economic or political, rather than immediate gains. The political scientist Nika Chitadze holds that the anticipated launch of the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars (BTK) railroad, as well as the planned construction of a new commercial seaport in Anaklia, will allow Georgia to gradually replace its dependence on the Russian market by elevating the country to an important transportation hub within China’s One Belt, One Road transcontinental transit initiative. This would, Chitadze argues, foster trade not only with China, but also with Japan, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore (Resonancedaily.com, June 19). However, this analyst, too, concedes that the much higher transportation costs of Georgian goods to China and other Asian countries in comparison to neighboring Russia undermine such an optimistic outlook.

Politically, Chitadze believes, “from the point of view of trade policy, Asian countries are more attractive to Georgia because from them there will be no danger that, for instance, China or Japan would close their market to our country due to political reasons, which is quite possible in the case of Russia” (Resonancedaily.com, June 19). Yet, including the PRC in the same category with Japan in this circumstance appears hardly warranted. Beijing has, in the past, also proven itself to be quite keen, when it sees a need, to use economic and cultural leverage to achieve desired political goals. Most recently, in the aftermath of the United States’ deployment of THAAD missiles to South Korea, China has aggressively pressured South Korea to remove them. As a result, a number of economic, educational and cultural Sino–South Korean ties were severed (see China Brief, April 20). Presumably, nothing precludes Beijing from applying a similar tactic against its newest free-trade partner Georgia, if the political situation were to require it in the future (see EDM, November 28, 2016).

In the aftermath of the FTA signing, on May 14, Georgia’s Minister of Finance Dimitri Kumsishvili announced, in Beijing, the establishment of a new Chinese “Georgian Development Bank,” co-founded by China Energy Company Limited and Eurasian Invest LLC. The bank has declared capital of $1 billion, but fulfilled capital of $300 million. The Georgian finance minister welcomed this institution as “important for the banking system” and “private sector development” (Netgazeti, May 14). Still, even experts who view such developments in the context of the FTA favorably are likely to acknowledge that, though the free trade deal with the PRC offers Georgia a formal opening, the South Caucasus country in facts lacks the potential, in terms of both the quantity and quality of its goods, to tip the scales of the trade balance in its favor. At the same time, China has obtained additional leverage to flex its economic muscle without much to hold it back in the Georgian market. Despite the slight improvement in the first half of 2017, the trade deficit between 2012 and 2016—i.e., even before the introduction of trade liberalization to and from China—comprised 78.6 percent on average. Considering the PRC’s overwhelming production and trade resources, the FTA is likely to further benefit the expansion of its already long-present trade dominance over Georgia.

The economist Paata Sheshelidze’s words tellingly sum up the heart of the matter: “A certain window has been opened, and, in the future, talented people will emerge. They will have an opportunity to enter new fields to sell their products. Who can make use of this, is secondary” (Commersant.ge, May 17). The positive prospects from the FTA for Georgia are rather vague, while China is free to continue to grow its economic footprint in Georgia, which raises uncertain political and security risks and consequences.