Hot Issue: Dabiq: What Islamic State’s New Magazine Tells Us about Their Strategic Direction, Recruitment Patterns and Guerrilla Doctrine

Hot Issue: Dabiq: What Islamic State’s New Magazine Tells Us about Their Strategic Direction, Recruitment Patterns and Guerrilla Doctrine

Executive Summary

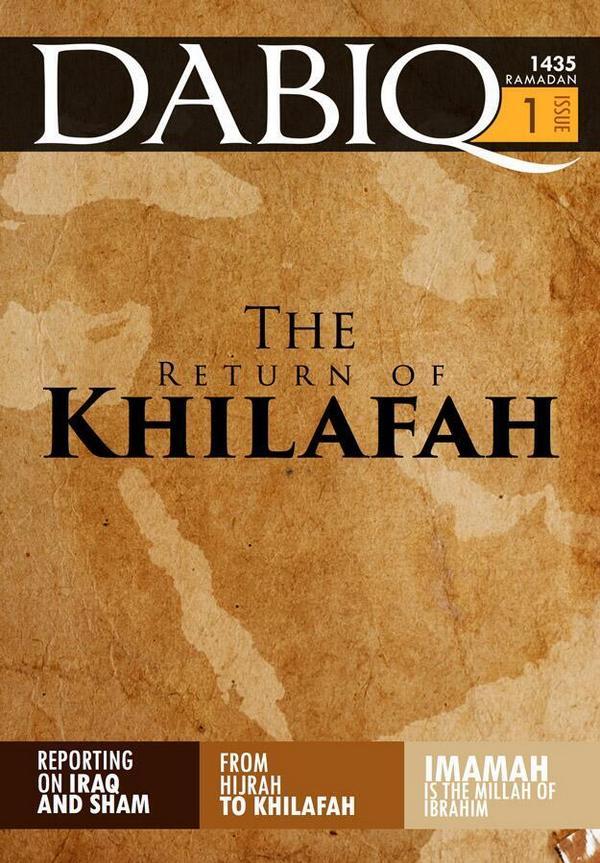

On the first day of Ramadan (June 28), the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) declared itself the new Islamic State and the new Caliphate (Khilafah). For the occasion, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, calling himself Caliph Ibrahim, broke with his customary secrecy to give a surprise khutbah (sermon) in Mosul before being rushed back into hiding. Al-Baghdadi’s khutbah addressed what to expect from the Islamic State. The publication of the first issue of the Islamic State’s official magazine, Dabiq, went into further detail about the Islamic State’s strategic direction, recruitment methods, political-military strategy, tribal alliances and why Saudi Arabia’s concerns that the Kingdom may be the Islamic State’s next target are well-founded.

Published in several European languages, including English, the magazine has a number of purposes. The first is to call on Muslims to come help the new caliph. Next, the magazine, comprising 50 vivid pages of color pictures, illustrations and artfully crafted text, tells the story of the Islamic State’s success in gaining the support of Syrian tribes, reports on the success of its recent military operations and graphically portrays the atrocities committed by its enemies, as well as vivid pictures of its own violence against Shi’ites. The premier issue also used classic Islamic texts to explain and justify the nature of the caliphate, its intentions, legitimacy and political and religious authority over all Muslims. Throughout its carefully constructed allusions, the magazine subtly appeals to the followers of other jihadist groups including the followers of the Islamic State’s foremost jihadist critics and potential followers in the Arabian Peninsula.

Another important purpose of Dabiq in the service of recruitment is to establish the Islamic State’s cosmic destiny by combining an eschatological account of coming battles gleaned from popular apocalyptic literature, the classical traditions of the Prophet Muhammad, prophecies and modern tactics taken from Salafi-Jihadist strategic literature. The strategic portion of this message is attributed to the original leader of the jihadist insurrection during the American occupation of Iraq, Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi. Taken together this mix is intended to capture the imagination of young warriors and inspire them to come and fight for Islamic State. This presentation will not solve the array of challenges facing the Islamic State, but it probably will help attract more young adherents as well as prove that al-Baghdadi and his advisors have developed a serious plan. It is important for Western countries to appreciate the dangerous instability this new movement, despite its obvious flaws, is capable of generating if left to its own devices.

Introduction

The hard part is just beginning for the Islamic State. Its predecessor ISIS swept across Sunni Iraq in a whirlwind of success it had prepared by using clandestine cells, terrorism and guerrilla tactics to harass, distract and exhaust the central government. In the north, the badly disorganized and dispirited Iraqi armed forces in Mosul panicked before the mere specter of ISIS shock troops. The tribes in the rest of the north became what Clausewitz referred to as the levee en masse (arming of the people) with ISIS suddenly in the lead role. Historically, the tribal leadership did not follow ISIS’ ideology, but the Islamic State now serves as the best organized and funded “enemy of my enemy” in both Iraq and Syria. It also has a windfall of money and arms to dispense to those willing to follow its lead.

In the long run the chips are stacked against the Islamic State. Hostile neighbors and other jihadists are determined to thwart its success; moreover, managing and governing territory requires a different skill set than conquering it. On the other hand, Islamic State guerrilla cadres and leadership have real world experience from both Iraq and Syria with sudden success followed by sudden failure. Its leaders’ ability to understand this reality and adapt to the challenges that are coming should not be underestimated, however. In addition to their own experience, the Islamic State’s leaders are eclectically drawing on extensive Arabic literature on global jihadist theory of guerrilla war, politics and governance, such as the writings of Abu Bakr Naji and Abu Mus‘ab al-Suri. Thus, Islamic State leaders know they must learn the political game in this new environment and make use of the best practices in public relations, which have served them well despite the horrific violence they have inflicted on all those perceived as enemies.

Dabiq: Symbol of Armageddon

The most significant of the Islamic State’s recent efforts at public relations and recruiting is the publication of the first issue of its official magazine Dabiq. Published in multiple languages (including English), Dabiq’s cover theme is “The Return of Khilafah” (caliphate). [1] According to the magazine, its title:

This area, at the time of publication under the control of Syrian forces loyal to Bashar al-Assad, is a symbol of the great clash-to-come between the forces of the new caliphate and the West in which the forces of Islam will be triumphant. This prophecy is traced to a classic hadith and was used by Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi to the effect that the promised victory in Dabiq will be the first step in the conquest of the world as symbolized by the anticipated defeats of “Constantinople” and then “Rome.” [3] In the apocalyptic tradition, Issa ibn Maryam (the Christian Jesus) will descend near Damascus to lead the army arriving from “al-Madinah of the best people.” [4] “Al-Madinah” can mean simply “city” as well as the city of that name in Saudi Arabia. By featuring this eschatology in such a prominent place, the magazine attempts to connect Islamic State and its new caliph to a cosmic purpose, obviously meant to have a romantic appeal to recruit young men looking for a cause.

The magazine is carefully crafted with symbolism that would be meaningful to jihadists, some amounting to “dog whistles” perhaps to signal to potential recruits that Islamic State is pursuing the stated goals of various jihadist groups and individuals that might otherwise be considered rivals or even enemies. For example, the use of the term “Millah Ibrahim” means the religious community or path associated with the patriarch Ibrahim (Abraham). The magazine has an extensive discussion of leadership entitled: “The Concept of Imamah (Leadership) is from the Millah (Path) of Ibrahim.” However, Millah Ibrahim is also the Arabic title of an influential 1984 jihadist tract written by the famous Palestinian-Jordanian ideologue Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi. Al-Maqdisi was a former teacher of Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi, but broke with him because of al-Zarqawi’s extreme violence against fellow Muslims. Accordingly, al-Maqdisi has not been a supporter of ISIS, but supports Ayman al-Zawahiri and al-Qaeda instead. By using this reference in its first magazine issue, it is most likely that the Islamic State is attempting to appeal to al-Maqdisi’s followers and admirers over the head of al-Maqdisi himself [5]

Among other things, al-Maqdisi’s book, Millah Ibrahim, attacks the Saudi royal family’s rule. Thus, this book and others by al-Maqdisi were popular with Juhayman al-Utaybi, the leader of the group of insurrectionists responsible for the violent takeover of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979. Some of these admirers later joined AQAP. [6] The message here could well be received as: the Islamic State follows al-Maqdisi’s jihadist views on the apostasy of Saudi Arabia, but unlike al-Maqdisi, Islamic State is willing to act on its views, not just theorize about them. Is the Islamic State appealing directly to young members and the leadership of AQAP in Yemen as well as to the disaffected youth in Saudi Arabia?

To cite one other potential appeal among numerous signals embedded in the terminology used in the glossy Dabiq, we need to consider the apparently straightforward subtitle of the magazine: “The Return of the Khilafah.” On March 18, 2012, the radical Pakistani extremist group, Hizb-ut Tahrir Wilayah Pakistan (The Liberation Party of the State of Pakistan) issued an online English language white paper with the same title. [7] Hizb-ut Tahrir, which is not a guerrilla group, argues that the caliphate should be based in Pakistan, but their arguments, though based in the circumstances of South Asia, are similar to Arab jihadist ideological discourse. Could it be that the Islamic State is trying to appeal to English-speaking Hizb-ut Tahrir radicals in Pakistan and Great Britain who want action rather than white papers? The most likely answer to this and other question is that ISIS appears to be appealing to all young, ideologically compatible Muslim men who crave action rather than words and might be lured to join the new caliphate’s army.

Khilafah Declared

Dabiq asserts that the Islamic State is synonymous with the caliphal state. To this end it features selections of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s public address in Mosul as the new self-declared caliph. The selections of statements are meant to demonstrate that one of the Islamic State’s major purposes is to return dignity to oppressed and humiliated Muslims, a theme consistently used by al-Qaeda’s media propaganda as well. The Islamic State emphasizes that it is a place for all races, ethnic groups and nationalities to gather together to fight in the trenches together as brothers. Reminiscent of al-Zawahiri’s message on numerous occasions, the new caliph announces the “heavy boots” of Muslims “will cause the world to understand the meaning of terrorism… will trample… the idol of nationalism, destroy the idol of democracy, and uncover its deviant nature.” This is a highly polarizing call for all Muslims to come and fight for the Islamic State, which claims to be the best path to liberating Mecca and Madinah from the Saudi government and Jerusalem from the Jews.

Reports on the Tribes

Dabiq features the purported results of two Sunni tribal assemblies near Aleppo, Syria. The magazine asserts that the Islamic State:

The “report” lists the tribal groupings in Syria that attended the assemblies complete with pictures of elders sitting in a forum and young men pledging bay’ah to the Islamic State and its caliph. The “head of tribal affairs” for the Islamic State announced that its mission was “neither local nor regional but rather global.” He related that Islamic State intended to implement Shari’a and listed recent successes in Iraq to include taking over the state of Ninewah, freeing Sunni prisoners, taking over the Mosul airport and military bases, demolishing the “Sykes-Picot” borders and opening a way between “Iraq and Sham.”

According to the magazine, the Islamic State representative stressed that he wanted the tribes help with their “wealth, their sons, their men, their weapons, their strength and their opinion, and encourage their sons and their brothers to join the military body of the Islamic State.” [9] The Islamic State representative also wanted to hear their advice and respond to their concerns; concerns, for example, about the Islamic State’s classic guerrilla strategy of taking ground and then leaving it when a conventional force challenges it. The Islamic State does not clarify what its response is to such concerns but its magazine reported what it promised to the tribes in concise bullet points. These include

· “Pumping millions of dollars into services that are important to the Muslims,”

· “Security and stability,”

· “Availability of food and consumer products in the market, and a

· “Reduced crime rate.”

Dabiq also reports that the tribes, for their part, asked the Islamic State to collect and distribute the widows and orphans tax and to give tribes weapons acquired from the regime or FSA.

From Hijrah to Khilafah

Dabiq spends considerable space using hadith to explain how the imamah (leadership) envisioned in the Millah Ibrahim is political as well as religious, and moreover, is the same as the leadership established by the Islamic State. Embedded in this discussion is an argument against democracy, which separates religious from political leadership. Towards the end of the magazine, the discussion turns to the strategy and tactics the Islamic State uses and how young men can help in the global struggle by migrating to support the caliph in his struggles to consolidate and expand the Islamic State.

The magazine calls for scholars, judges and people with military, administrative and other expertise as well as physicians and engineers to come serve in the Islamic State. Naji and al-Suri’s ideas (without attribution) are then described as lessons learned in the fighting in Afghanistan and elsewhere and applied by Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi, the founder of what became ISIS. In a general outline, Dabiq describes a three-stage guerrilla warfare structure based on Maoist ideas as interpreted by numerous left-wing insurrectionists in the 20th century and jihadist groups in the 21st. [10]

The political-military stages in Abu Bakr Naji’s writings mirror the ones Dabiq ascribes to al-Zarqawi and uses similar technical vocabulary: “nikayah” (damage or terrorist tactics), “tawahhush” (mayhem or savagery) and “tamkin” (consolidation or establishing a state). All of these stages ideally take place in a country with a weak enough central government with regions that jihadist guerrillas can target. The first stage, nikayah operations, involves terrorist attacks to frustrate the central government and create as much chaos as possible to cause the central government to withdraw forces from the target region. When the chaos is sufficient, referred to here as “tawahhush,” a region is so destabilized that the mujahideen are able to take control of the area or areas in a primitive government that Naji called “administration of savagery” in his work Idarah al-Tawahhush (Administration of Savagery). [11]

Dabiq comments that al-Zarqawi had intended to initiate wider and more complex attacks in Iraq to consolidate these jihadist-administered areas into a state, using Naji’s term for establishing an Islamic state, “tamkin.” This third stage occurred, according to Dabiq, when al-Zarqawi’s successor, Abu Omar al-Husayni al-Baghdadi, established the Islamic State of Iraq. Furthermore, the magazine asserts, this was the first state “set up exclusively by the mujahideen – the active participants in the jihad – in the heart of the Muslim world just a stone’s throw away from Mecca, al-Madinah, and Bayt al-Maqdis [Jerusalem].” After Abu Omar’s death, new leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi established the khilafah. It is the clear intention of Dabiq to show that the Islamic State is the realization of the life-long dream of Ayman al-Zawahiri, currently the Islamic State’s most prominent jihadist critic. All this is standard jihadist grand strategy and signals that the two holy cities in Saudi Arabia and then Jerusalem are the ultimate targets. Overlaid onto this political-military strategy is a related action plan belong to the current phase when the caliphate is newly established. This five-phase plan appeals to Sunni Muslims and those desiring to convert:

· Join up;

· Help destabilize the tyrant to further the goal of expansion;

· Consolidate new areas;

· Extend the caliphate over the new areas.

Conclusion

Dabiq provides the first admission, albeit indirectly, that the Islamic State and previously ISIS have been following a strategy as laid out in broad strokes by Abu Bakr Naji and informed by the teachings of Abu Mus’ab al-Suri. This strategy is linked to the founder of this Salafi-Jihadist current, Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi, in his terror campaign in Iraq until his death in 2006. The magazine anecdotally connects the Islamic State to tribal coalitions inside Syria and Iraq. Through its allusions and usurpation of terms and titles, the magazine seeks to connect the Islamic State to the goals of major organizations and jihadist thought leaders even when they are known to oppose the Islamic State. The appeal encompasses the entire jihadist movement, including al-Qaeda affiliates and non-al-Qaeda extremists like Hizb-ut Tahrir with its large clandestine following in Pakistan, Great Britain and elsewhere. With its apocalyptic aura the Islamic State is attempting to appeal over the heads of other communities to disaffected youth and motivated young professionals. In its context, it is a powerful message; despite its serious shortcomings, the Islamic State will continue to create savagery and mayhem until the new state and its fighting vanguard can be checked, either by an outside force or, more likely, by the very people now under its harsh rule.

Dr. Michael W. S. Ryan is an independent consultant and researcher on Middle Eastern security issues and a Senior Fellow at the Jamestown Foundation. He is the author of Decoding Al-Qaeda’s Strategy: The Deep Battle Against America (Columbia University Press, 2013).

Notes

1. For an online version of Dabiq, see https://www.writeurl.com/publish/ujzjvs1ep33kyflhw4ey

2. Ibid. p.4.

3. Ibid. p.2.

4. See Jean-Pierre Filiu, Apocalypse In Islam, trans. M. B. DeBevoise, (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011).

5. For a purported switch of allegiance from al-Qaeda to the Islamic State, see the jihadist forum al-Melahim wa’l Fitan claiming to record the pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State of nine “al-Qaeda soldiers,” including one claiming to be al-Maqdisi’s brother. The document is addressed to AQAP indicating that the signers were members of AQAP, https://alfetn.net/vb3/showthread.php?t=82569. Aaron Zelin, who brought attention to this document, referred to the group as a “breakaway faction” of AQAP; see Aaron Zelin, “The War between ISIS and al-Qaeda for Supremacy of the Global Jihadist Movement,” Research Note 20 (June 2014, The Washington Institute For Near East Policy).

6. For a full account of al-Maqdisi’s thought, influence, and relationship to Saudi Arabia and visits with Juhayman’s followers, see Joas Wagemakers, A Quietist Jihadi: The Ideology and Influence of Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

7. See https://www.hizb-ut tahrir.org/PDF/EN/en_books_pdf/PK_Return_of_the_Khilafah_English_OK_rev.pdf for an online version of Hizb ut Tahrir’s “Return of the Khilafah;” For a profile of this group see Farhan Zahid, “The Caliphate in South Asia: A Profile of Hizb-ut Tahrir in Pakistan,” in Terrorism Monitor, July 10, 2014, https://www.jamestown.org/single/article_id=42600&no_cache=1.

8. Dabiq, p.12.

9. Ibid. p. 13.

10. For an analysis of jihadist political-military strategy, see Michael W. S. Ryan, Decoding al-Qaeda’s Strategy: The Deep Battle Against America, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013).

11. Abu Bakr Naji, Idarah al-Tawahhush: Akhtar Marhalah Satamurru biha al-Ummah (The administration of savagery: the most dangerous phase through which the ummah will pass), N.p.: Markaz al-Dirasat wa al-Buhuth al-Islamiyyah, Nd.), https://www.tawhed.ws/a?a=chr3ofzr.