Iran Increasing Its Influence in Central Asia With Expanded Trade across Turkmenistan

Iran Increasing Its Influence in Central Asia With Expanded Trade across Turkmenistan

Executive Summary:

- Iran and Turkmenistan are rapidly expanding transit routes, enabling Tehran to expand its trade with Russia in support of Moscow’s effort to circumvent Western sanctions and boost its economic links with other Central Asian countries.

- This route is increasingly important to Russia because of continuing uncertainties in the South Caucasus and to the countries of Central Asia, which want to balance their role in east-west trade with that of north-south commerce.

- Iran’s expanding influence is almost exclusively economic. This will allow the Islamic Republic to spread its ideological message, something the West and Central Asian governments have reason to fear but some opposition groups welcome.

For most of its just over 30 years of independence, Turkmenistan has been left out of discussions on Central Asia as well as both north-south and east-west transportation routes linking the region to the rest of the world. Over the last two years, however, the situation has changed dramatically as Ashgabat has opened up and assumed a more active role internationally. Turkmenistan has assumed an ever-more important role as a conduit for north-south and east-west trade, linking China and Europe, Russia and Iran, and the landlocked countries of Central Asia with the outside world (see EDM, December 15, 2022, May 11, 18, 2023). The role of China and east-west trade via Turkmenistan has garnered much international attention. A key dynamic that has been missed, however, is Iran’s ever-increasing importance in Central Asian trade patterns. Moscow, Ashgabat, and the other Central Asian capitals welcome this trend, but many in the West fear it. This is due to concerns that Tehran will likely utilize its newfound economic leverage in the area to promote the regime’s Islamist message (see EDM, January 12, 2023, July 23).

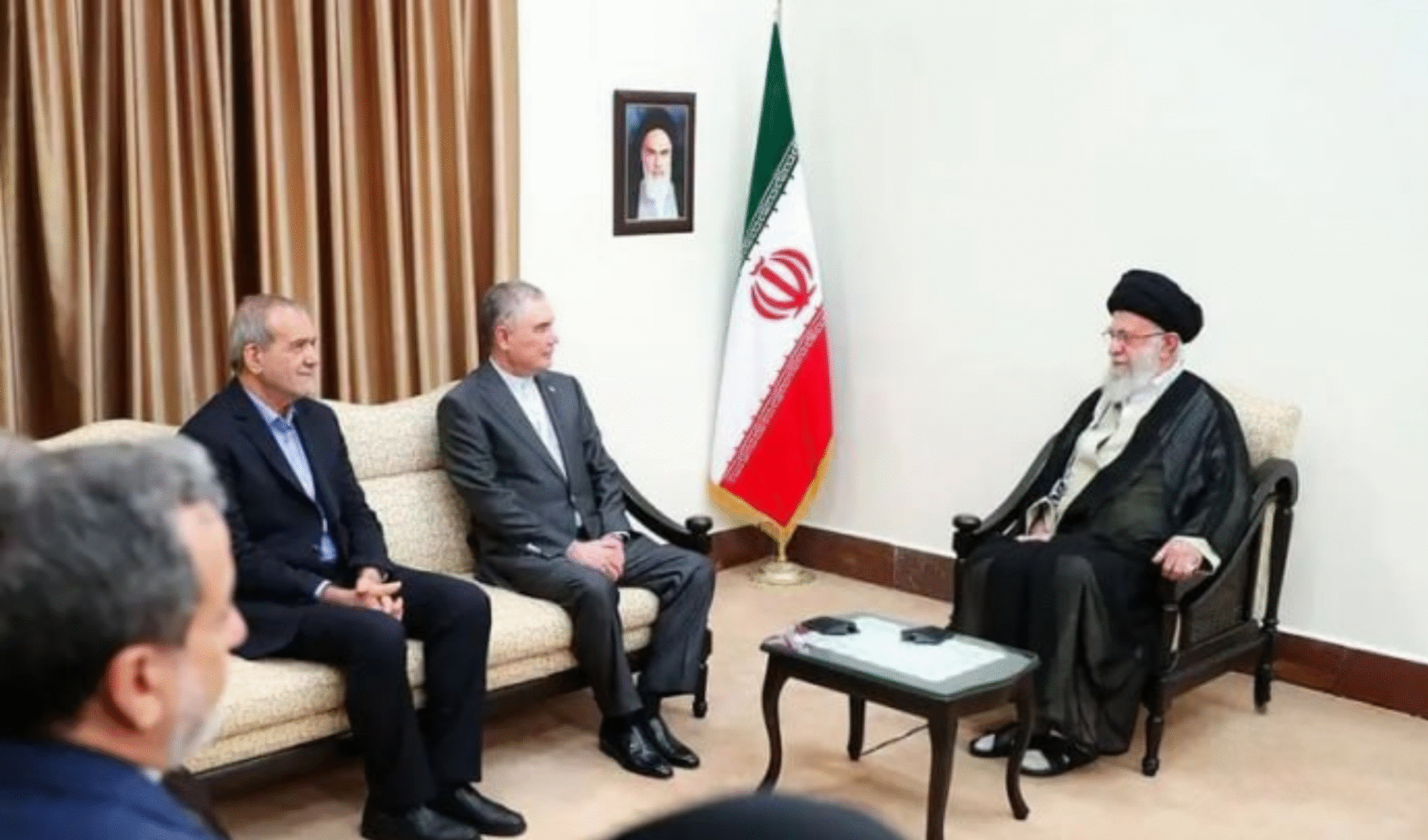

Iran has been focused on developing trade routes to Central Asian countries and onward to Russia for several years (see EDM, December 15, 2020, April 14, 2021, October 16, 2023). Given Iran’s geographical location, this is entirely natural. The only other routes in and out of Central Asia are via Russia, China, Afghanistan, or across the Caspian Sea; each of these options pose their own political and logistical challenges. Iran’s ambitions to become a dominant player in Central Asian trade assumed new and larger dimensions with the signing of agreements between Turkmenistan’s former president and current national leader Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov and Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in late August (Eurasia Today, August 26, 29; Kaspiskii Vestnik, September 2). Trade across these routes has increased by as much as 30 times since 2023, and the new accords are slated to increase it further over the next two or three years, Russian experts say (Kaspiskii Vestnik, August 31, September 4). If those projections hold, railways and pipelines across Turkmenistan will become major transit routes not only for the countries of Central Asia but for Russia and Iran as well.

Iran has moved quickly in this direction for three major reasons. First, policymakers in Central Asian states desire multiple export and import routes so that no one country can dominate them. Second, Russia is developing a burgeoning security alliance with Iran and has an interest in projecting power southward toward the Indian Ocean. Third, Russia and Iran face numerous difficulties in conducting trade through either the Caucasus or the Caspian Sea.

Since gaining independence in 1991, the Central Asian states have typically been viewed as objects to be manipulated by outside powers rather than agents to be understood in their own right. In response, these countries have sought to develop ties with multiple partners to prevent being dominated by any one of them. Many in the West initially viewed this as competition between Türkiye and Iran, whose contrasting ideological and political positions meant that the West supported the former and opposed the latter. Then, attention shifted to geopolitical competition among Russia, China, and the West over existing routes rather than to the possibility that new ones could open up. Unsurprisingly, albeit for very different reasons, many in the capitals affected have welcomed the expansion of the Turkmenistan route, and Iran has worked hard to exploit that fact (Kaspiskii Vestnik, August 31).

The combination of the second and third factors has proved to be more important. Due to Western sanctions, Russia has formed a close security partnership with Iran and sought both to import Iranian weapons to be used in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine and to end run Western sanctions by shifting trade to the south (see EDM, February 22). Because of continuing uncertainties and turmoil in the South Caucasus, the difficulties Moscow and Iran face in opening train routes in northern Iran, and bottlenecks in any plans to use the Caspian as an alternate route, the Russian government has increasingly shifted its attention to developing trade with Iran via the countries of Central Asia (see EDM, April 11, 2023; Eurasia Today, September 11). Moscow has backed the development of a corridor across Turkmenistan to Iran, even if it might be used against Russia in the future. This support has made it easier for both Ashgabat and Tehran to reach their own agreements (Kaspiskii Vestnik, August 31; Commonwealth of Independent States, September 10).

Iran has a larger economic agenda than just the expansion of transit corridors. Ashgabat and Tehran are discussing the creation of special joint zones of economic activity and other steps to increase economic interaction between them (Kaspiskii Vestnik, August 27). How far the two will go, however, depends not only on the success of the transit corridor but also on the international situation and whether Turkmenistan decides against further development of ties out of fear that it could lose control of the domestic situation. Turkmenistan is anything but stable, however calm Ashgabat’s repression has made it appear. Poverty and even hunger remain serious problems, especially given increasingly severe water shortages. Conflicts within the elite appear to be on the rise, and ethnic tensions are certainly growing, with minorities leaving the country when they can. Islamist thought is becoming ever more of a problem, with Ashgabat now closing mosques, a step that makes contact with Iran especially problematic (Window on Eurasia, January 17, 2022, February 26, October 15, November 17, 27, 2023). In the past, Ashgabat has warned of the danger of Iranian-style popular uprisings in Turkmenistan, a danger that has not disappeared and may be on the rise (Fergana, January 9, 2018).

Iran may find it increasingly difficult to expand its presence in Turkmenistan and use that as a springboard for achieving similar successes across Central Asia (IA-Centr.ru, May 3). For the moment at least, Iran is gaining new footholds in the region with the backing of Moscow, especially among opposition groups. This is something certain to sound alarm bells in Western capitals, which have good reason to fear that the expansion of Iran’s economic influence will be followed by the growth in its ideological influence as well. This development would no doubt threaten Western interests in the region. What remains to be seen is whether Moscow and Beijing will realize that such Iranian gains would threaten them as well in the long run, however much they may currently be benefiting.