Is the RCEP China’s Gain and India’s Loss?

Is the RCEP China’s Gain and India’s Loss?

Introduction

On November 15, fifteen nations in the Indo-Pacific region — including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and the ten ASEAN members Brunei, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines — signed the world’s largest trade agreement. Known as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the new trading bloc will cover 2.2 billion people and its member states’ combined GDP of $26.2 trillion accounts for around 30 percent of total global GDP. The deal’s finalization comes about a year after India announced its decision to not join the grouping, based on its perception that the terms of the agreement were skewed in China’s favor. India also feared that the deal would allow Chinese goods to flood Indian markets, threatening domestic industries. Regardless of India’s withdrawal, the pact represents a milestone in China’s ambition to become a regional trade lynch-pin.

The RCEP, first proposed in 2012, was negotiated over the course of 46 trade representative meetings and 19 ministerial meetings. As the world continues to grapple with the economic impact of Covid-19, the RCEP has the potential to reshape the geostrategic landscape in the Indo-Pacific with dramatic consequences. The RCEP could come into effect as early as mid-2021, but resistance to the deal within the national parliaments of states that have yet to ratify would likely drive its date of implementation back to January 1, 2022. Australia (currently undergoing a tumultuous diplomatic and trade war with China), Malaysia, and Thailand are among the most likely to delay ratification (China Briefing, November 17; SCMP, November 16).

The mega-pact’s signing comes after months of increasing geostrategic military maneuvers undertaken by Beijing in connection with various territorial disputes, from repeated coast guard patrols aimed at asserting its de facto control over the Senkaku islands in the East China Sea; to resource control disputes with Vietnam and Malaysia in the South China Sea and the border conflict with India in the Himalayas. China’s flexing of its economic and military weight has grown rapidly over the past year, demonstrating that its leadership feels confident to override countervailing opinions and ignore criticisms (Eurasia Review, November 18). These developments put the theory of China’s “peaceful rise” (中国和平崛起, zhongguo heping jueqi)—a concept first introduced by Zheng Bijian in November 2003—under question.[1] Discussions of the RCEP’s utility in promoting regional multilateralism need to be balanced against the realities of China’s recent actions against its neighbors.

RCEP: Pros and Cons

Defenders of the RCEP say that the pact will lower tariffs between member countries, open up regional trade opportunities and promote investment to benefit emerging economies. While it includes some provisions on standardizing intellectual property regimes, the agreement does not cover environmental protections or labor rights (Channel News Asia, November 15). The RCEP’s provisions on e-commerce and digital trade are also weak, which proved an indelible sticking point for India (The Hindu, October 11). One analyst concluded that the RCEP’s language on digital trade is vague “to the point of rendering the provisions meaningless” for the liberalization of cross-border digital transfers and data flow (CIGI, November 23).

With India and the United States notably excluded from the deal, China could leverage its position as the largest economy within the RCEP to further exert its influence in the region. Critics of the RCEP see it as a China-driven coup enabling Beijing to extend its influence across the Indo-Pacific (Quartz, November 16; Economic Times, November 17). China has faced little regional competition from the United States since the Donald Trump administration pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, arguing then that the world’s then-largest trade pact would take away U.S. jobs. The Shinzo Abe government of Japan resurrected the TPP in a new form as the Comprehensive Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP); critics have noted that the RCEP is not extensive as the TPP or its successor CPTPP.

India’s Withdrawal From the RCEP

India pulled out of RCEP talks in November 2019, claiming that the negotiations did not sufficiently address its “significant outstanding issues” (LiveMint, November 4, 2019). As the regional balance of power shifted in the eight years since talks began, Prime Minister Narendra Modi faced mounting pressures at home to take a tougher stance on the terms of the free trade agreement (FTA). India’s decision to stay out of the RCEP was hardened by fears that its domestic producers would be hard hit if the country was flooded with cheap Chinese goods under the umbrella of free trade. Textiles, dairy, and agriculture were flagged as three particularly vulnerable industries (Asia Times, November 15).

In the wake of the renewed border tensions, anti-China sentiment (most visibly expressed by the “Boycott China” movement) has been on the rise. India’s government moved to restrict Chinese foreign investment and banned over 200 Chinese apps from its domestic internet, which the Indian government asserted was crucial for its “national security” but Chinese officials criticized as violating WTO rules (TechCrunch, November 24; Hindustan Times, November 25). Such actions have proven wildly popular back home but would likely not be permitted under the RCEP.

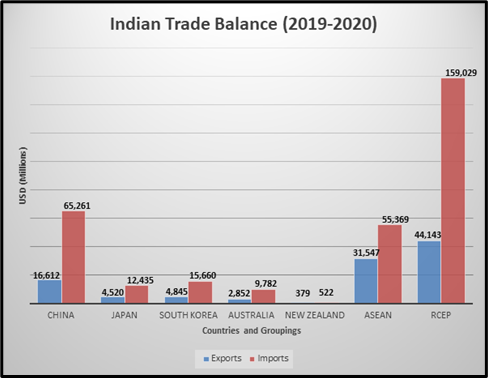

Back in 2019, India’s sticking point proved to be the absence of mechanisms to check trade imbalances. India felt that there were “inadequate” protections against a possible surge in imports with the possible circumvention of rules of origins – the criteria used to determine the national source of a product – and the absence of which could allow some members to dump products by routing them through other countries (The Telegraph (In.), April 11, 2019). It was unsuccessful in including countermeasures such as an auto-trigger mechanism that would raise tariffs on specific products once imports crossed a certain threshold (Indian Express, November 17). An internal assessment carried out by the Indian government this year showed only a “moderate utilization rate” of free trade agreements with neighboring economies over a five-year period and confirmed that although India’s deficits with RCEP were marginally reduced in most cases, its total deficit with ASEAN countries as a whole had increased over the past two years (Indian Express, November 17). Ultimately, India’s leadership concluded that not signing an agreement was better than signing a bad agreement, fearing that its pre-existing trade imbalance (see figure below) with RCEP nations would considerably widen under the agreement without appropriate safeguards (India Today, November 15; Indian Express, November 17).

In addition to economic concerns, escalating bilateral tensions and the recent border stand-off with China likely cemented India’s decision to shun the RCEP. Yet some domestic commentators have argued that the decision to abstain from the RCEP will cost India heavily (Economic Times, November 17). By staying out, India now has less scope to tap the large market that the RCEP represents. Based on this perspective, India’s decision could be seen as turning its back on the multilateralism espoused by the RCEP.

Options to (Re)Join

Japan maintains good relations with India, and Japanese negotiators worked hard to include language in the final version of the RCEP which would allow India to join the agreement at any time, without having to wait the 18 months stipulated for new members (Indian Express, November 16; Economic Times, November 17). The conservative newspaper Sankei Shimbun published an editorial shortly after the deal was finalized that expressed caution about the deal’s implications for Chinese influence but still suggested, “Japan should be persistent, and try its best to get India to join” (Sankei Shimbun, November 17).

India recently signed military cooperation agreements with both Japan and Australia, strengthening the “Quad” security framework and demonstrating a shoring up of relations between “like-minded” democratic nations in the Indo-Pacific (Rediff, September 12; China Brief, October 30). A nascent Resilient Supply Chain Initiative (RSCI) proposed by India, Japan and Australia in September could also serve as leverage against China’s growing regional influence and might not be incompatible with the RCEP (Financial Express, September 11).

India’s decision to stay out of the RCEP shall remain under scrutiny for quite some time. When India said no to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2017, it faced accusations of isolationism. Three years later, India’s supporters have grown in number, with criticisms of the BRI by like-minded democracies increasing. If India chooses to “remain off the menu but on the table” by seeking observer status in the RCEP, that in itself would be a development worth watching (Indian Express, November 19).

China’s Gains From the RCEP

The U.S. President-elect Joe Biden has expressed a desire to resurrect America’s declining engagement in Asia through an “alliance of democracies” (China Brief, December 10). In light of the U.S.’ projected return to the region, the RCEP will shore up China’s position as a key economic partner with Southeast Asia, Japan and South Korea, enabling it to shape the region’s trade. At the time of writing, there are no details on which products and countries would see the first reductions in tariffs. A clearer picture shall emerge after the participating countries ratify the agreement—but as already mentioned, this process poses further challenges. Even absent major economic gains, the RCEP represents a strategic windfall for China.

If the RCEP helps its member economies to bounce back from the pandemic, it could dramatically improve its public profile and help China to recover a reputation hard hit this past year. But such rosy predictions are at least two to three years away from reality. It’s easy to imagine how the RCEP will lend heft to China’s broader regional geopolitical ambitions and provide new opportunities for its BRI. The Chinese state tabloid Global Times has remarked that India committed a “strategic blunder” and “missed the bus” to long-term growth by staying out of the mega-pact (Global Times, November 13; Global Times, November 15). Specifically, one Chinese South Asian expert, Liu Zongyi, blamed “interest groups” within Modi’s government for the decision. The official news agency Xinhua hailed the deal as “…not only a monumental achievement in East Asian regional cooperation, but more important, a victory of multilateralism and free trade” (Xinhua, November 15).

China succeeded in excluding Taiwan—which it regards as a breakaway province with no sovereign power—from the massive regional trade deal. This marks a major discursive triumph for the PRC, which has spent decades lobbying against Taiwan’s inclusion in global multilateral organizations. Arguably one of the RCEP’s greatest achievements is the creation of a FTA between Japan, South Korea, and China, which are all major trading partners for Taiwan. This could be potentially catastrophic for the island nation; Taiwan’s Minister of Economic Affairs responded to the RCEP’s finalization by calling for domestic industries, particularly the petrochemical, upstream textile, and machine tool industries, to “brace for a major blow” (Taiwan News, November 16). Taiwan’s government has said that it will step up its efforts to join the Japan-led CPTPP to circumvent the RCEP’s impact, although it may be stymied there by China as well (Focus Taiwan, November 15).

Conclusion

Although it has been widely argued that the RCEP is dominated by China, many of the deal’s advocates have emphasized that its formulation and future operation were and shall be consensus-based. China’s role in the deal should not be overhyped, such voices warn, arguing instead that the deal should be seen as a “triumph of ASEAN’s middle-power diplomacy” (Brookings, November 16; Asia Nikkei, November 27). The RCEP creates momentum for free trade at a time of increased global trends towards protectionism and nationalism. It sends a message that the world is returning to globalization.

Notwithstanding the symbolic and strategic victory of the RCEP for China, analysts expect that China’s gains from the RCEP deal would likely be marginal, and are not expected to offset the negative impact of its ongoing trade war with the U.S. (SCMP, November 16). At a minimum, the RCEP represents a mechanism for China to expand its sphere of influence in the Indo-Pacific in the face of broader U.S. economic pressure. The deal will likely help China to avoid losing relevance in international value chains shifting in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. Further predictions on the RCEP’s regional importance and impact will have to await the deal’s ratification by member nations.

Prof. Rajaram Panda was formerly Lok Sabha Research Fellow, Parliament of India and now Member, Governing Council of Indian Council of World Affairs, and Centre for Security and Strategic Studies, both in New Delhi. He was also Senior Fellow at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses and ICCR Chair Professor at Reitaku University, Japan. He may be reached at: rajaram.panda@gmail.com.

Notes

[1] See: Bijian, Z., “A New Path for China’s Peaceful Rise and the Future of Asia: Bo’ao Forum for Asia,” November 2003, in China’s Peaceful Rise: Speeches of Zheng Bijian 1997-2005 (pp. 14-19), Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctt127xn6.5.