Kazakhstan’s Transport Policy Faces Political Dilemma

Kazakhstan’s Transport Policy Faces Political Dilemma

Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev on his recent visit to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) praised China’s involvement in an important joint $7.5 billion transnational road construction project as an example of their partnership. He said Kazakhstan started the construction of its section of the 3,000 kilometer highway that will link Western China to Western Europe and called on the government of the UAE to focus on similar joint projects (Kazakhstanskaya Pravda, March 19).

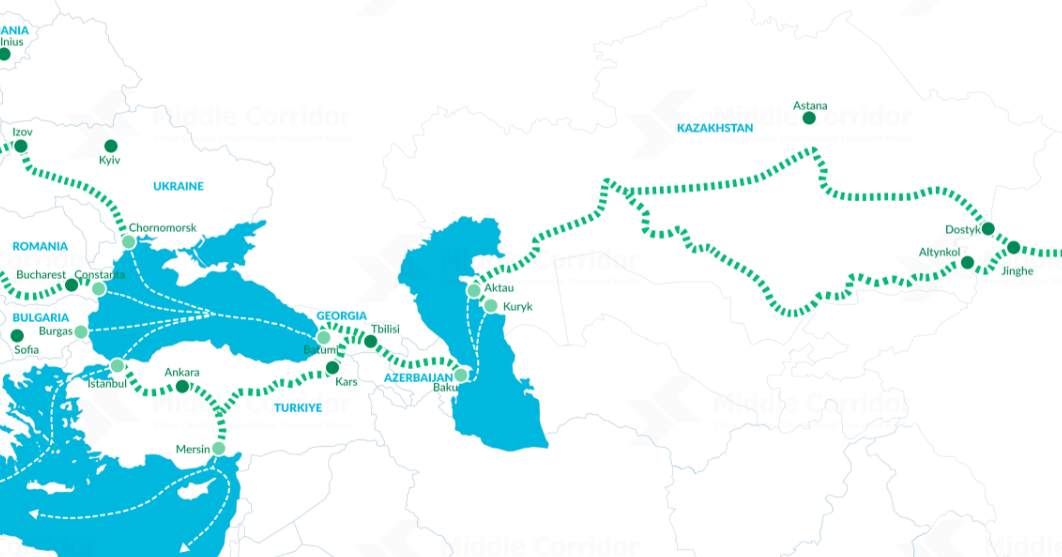

Faced by the severity of the financial crisis, Kazakhstan’s government had to radically cut state expenditure on major construction projects, prioritizing instead an increase to budget allocations for social spending. But ambitious plans to modernize transport and communications remain on the priority list. The long-term government program, devised by the Ministry of Transport and Communications, aims to integrate Kazakhstan into the global transportation system as its main objective. Due to its geographical location, Kazakhstan benefits from transit fees for Chinese, European and South-East Asian cargo flows. The strategic plan of the Transport and Communication ministry for 2009-11 envisages Kazakhstan’s participation in the creation of a transport corridor linking western China with Western Europe, with a 2,287 kilometer stretch of running through Kazakhstan. Such politically important, but economically ambiguous projects place enormous financial strains on the cash-strapped Kazakh economy at a time when more than 19 billion Tenge is needed for road maintenance and repairs of the national road infrastructure in 2009 (Kazakhstanskaya Pravda, March 5).

It seems, Kazakhstan’s transportation policy is often governed by political considerations to the detriment of economic rationale. China, which is a close partner of Kazakhstan within the Shanghai Organization for Cooperation (SCO) is keenly interested in opening the low-cost route to Europe for the shipment of its cargo through Kazakhstan. Experts estimate that using the Kazakh railroad to Europe instead of the Russian Trans-Siberian railway, shortens the distance for Chinese cargo by 1,000 kilometers. Last year, Kazakhstan’s government promised Beijing to set flexible prices for the transit of Chinese cargo bound for Europe. Astana sees itself as an important transport link between Europe and China and a vital economic partner of the West; which was one of the factors it used in bargaining for the country’s OSCE chairmanship in 2010. On the other hand, true to its constantly trumpeted multi-vector foreign policy, Kazakhstan toys with the Russian-favored Eurasian Economic Community (EurAsEc) and the Customs Union project with Belarus and Russia, although the customs union trinity has never come near reaching a comprehensive agreement on unified customs tariffs.

Nevertheless, Tair Mansurov, former Ambassador of Kazakhstan to Russia and the current secretary-general of EurAsEc believes the organisation will set up its own unified transport network, logistics center and infrastructure. He also disclosed that EurAsEc was currently working on a modernization program for four transport corridors including the Eurasian direction from China to Europe via Kazakhstan and Belarus, a North-Western corridor linking Central Asia, Russia and Baltic states, a South-Western route providing access for Central Asian states to Russian and Ukrainian seaports and an eastern route from Central Asia to the seaports of Russia’s Far East and Asian Pacific region (Kazakhstanskaya Pravda, March 13).

Despite the ongoing tensions between the U.S. and Iran, Kazakhstan has managed to strike a balance between the sides and maintained trade relations with Iran, regarded by Astana as an important economic partner and a gateway to the Gulf States, Turkey and the EU. Currently Kazakhstan almost exclusively uses the Caspian maritime route to deliver one million tons of oil annually to the Iranian seaports of Neka and Amirabad on an exchange basis. But the limited capacity of Kazakhstan’s tanker fleet and the seaport of Aktau, the only international port in the country, handling 9.3 million tons of oil each year, are likely to fall short of the expected standards if Kazakhstan is to increase the volume of oil export to Iran as projected. Therefore, Astana is contemplating additional export routes in that direction.

On October 16, 2007, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Iran signed an agreement to lay 700 kilometers of railroad track from Uzen in Western Kazakhstan to Gorgan in Iran transiting Turkmenistan. The railroad, with a projected annual capacity of five million tons of cargo, was initially planned to be completed by December 2011. Turkmenistan’s President Gurbanguly Berdimukhamedov was rather optimistic, saying the railroad would be put into operation in 2010. Turkmenistan started the construction of its section of the railroad at Bereket station in December 2007. However, last January Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Transport and Communications confirmed that the work on the country’s section of this railroad might be delayed for more than eighteen months for financial reasons (RZD Partner, January 23).

One reason for Kazakhstan’s lukewarm attitude towards the Iranian railroad project may be its warming relations with the West in anticipation of its OSCE chairmanship. Iran also treats Kazakhstan’s rapprochement with the West with a great deal of mistrust. Kazakhstan needs American and European technical aid to upgrade its obsolete transport facilities. Nonetheless, the intensified trade with China, Russia and Iran will remain at the heart of the transport policy of Kazakhstan.