Limited Payoffs: What Have BRI Investments Delivered for China Amid the Coronavirus Outbreak?

Limited Payoffs: What Have BRI Investments Delivered for China Amid the Coronavirus Outbreak?

Introduction

The coronavirus outbreak, now declared to be a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO, March 11), offers a prism through which to assess how China interacts with the rest of the world in a time of crisis—one that was at first confined to China’s borders, but has since become a global emergency. Some commentaries on the connection between the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have portrayed Xi Jinping’s centerpiece foreign policy program as a dangerous vector enabling the pandemic—even though China was engaged in international trade and transportation prior to the commencement of the BRI in 2013 (Foreign Policy, January 24).

For its part, state media in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has linked BRI relationships to support for China amid the initial stages of the crisis, citing positive examples of support from media outlets in South Africa, Russia, and Pakistan (People’s Daily, February 20). More recently, as the spread of the disease has abated in China and increased elsewhere, Chinese authorities have sought to illustrate their support, via the “warmth” of the Belt and Road, for current hotspots such as Italy and Iran—while also criticizing the U.S. response to the crisis (Zhejiang News, March 12). Such developments in China’s foreign relations amid the coronavirus outbreak offer a window to assess the effectiveness of the BRI in one of its central goals: namely, expanding the soft power available to the PRC.

Applying an understanding of soft power as a state’s ability to induce other states to take actions favorable to its own interests, available evidence across domains related to the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic—such as the issuance of evacuation orders, and restrictions on public transportation—indicates that BRI investments have had only modest success in building China’s soft power. International support for China was piecemeal and rhetorical, leaving China economically and politically isolated. Demonstrating the lack of soft power available to Chinese authorities, the state tabloid Global Times demanded on February 12 that countries that “have completely cut off traffic communications with China” should “reconsider and revoke these practices” (Global Times, February 12).

Decisions Regarding Passenger Transportation

Amid the shutdown of international air services to China in January and February, a significant proportion of suspensions were accounted for by airlines from countries that have not received Belt and Road funding—including British Airways, Air Canada, and the primary U.S. carriers offering flights to China (Delta Airlines, American Airlines, and United Airlines). However, airlines from countries that have received significant loans from Chinese policy banks, or other forms of investment or development assistance, have also suspended service to China. A partial list of these airlines includes Egyptair, Kenya Airways, and Rwandair (all of which are fully- or partially-state-owned)—despite governments in these countries receiving funding from the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank for ongoing infrastructure projects. This decision-making indicates that China’s provision of subsidized lending is far from a guarantee that it will accrue asymmetric political influence in the recipient countries.

Despite these suspensions, influence yielded by the Belt and Road Initiative may have impacted the decision-making of other airlines. On January 31, Pakistan International Airways initially elected to suspend service after local authorities ordered the cancellation of all flights to and from China (Anadolu Agency, January 31). Just three days later on February 2, Pakistani aviation authorities lifted all restrictions—before reimposing them on February 24 (The News). Similarly, despite coming under public criticism, Ethiopian Airlines has also continued to operate scheduled service to China, with airline chief Tewolde GebreMariam commenting that “it will not be morally acceptable to stop flying to China today” (South China Morning Post, February 11). As of March 5, the airline was still operating services to China (CGTN, March 5). It is not a coincidence that both countries are listed in a Center for Global Development ranking of countries with the greatest sums in their “BRI lending pipeline” (Center for Global Development, March 4, 2018).

Taking on large sums of Chinese development finance has not precluded other countries from placing heavy restrictions on transport links with China. Initially, however, Russia announced the closure of its borders with China to passenger traffic, and the grounding of all bilateral air travel other than services to Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport. These restrictions were subsequently tightened, with the announcement that PRC nationals would temporarily be barred from entering Russian territory effective February 20, with the exception of transit passengers (Moscow Times, February 18). These steps were taken despite the fact that Chinese financing plays a major role in many of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s economic revitalization projects, including the development of gas production plants in the Russian Arctic. While the decisions taken by Pakistani and Ethiopian aviation authorities can be ascribed to soft power developed by China via the Belt and Road Initiative, Russia’s decision to halt border crossings shows that Beijing’s economic influence cannot reliably trump the self-interest of recipient states (China Brief, February 28).

Evacuation Orders

While many BRI partner countries suspended bilateral air travel and repatriated their citizens from Wuhan, these governments have also sought to maintain close relations with Beijing in ways that do not harm their own citizens. Countries including Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Korea have issued statements of support (CGTN, February 7). Moreover, according to the Chinese government’s Belt and Road Portal, countries including Bangladesh, Japan, Thailand, South Korea, Malaysia, India, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Hungary, Belarus, Turkey, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Egypt, Australia, New Zealand, and Trinidad and Tobago have all provided some form of material assistance to China in response to the outbreak (Yidaiyilu.gov.cn, February 13). While it cannot be known how these countries would have responded were it not for the Belt and Road Initiative, there is a logical connection between the large sums of money China has provided for projects in these countries with their decisions to provide aid to Beijing in its time of need.

However, the provision of material aid is only part of the story. According to statistics released by the PRC National Immigration Administration (NIA) on February 10, as many as 128 countries have imposed some form of immigration restriction (ranging from entry bans to temperature checks) on travelers from China since the outbreak began (NIA.gov.cn, February 10). Of the 115 countries that Chinese authorities list as “international cooperation partners” of the Belt and Road Initiative, at least 91 rank among those disclosed by the NIA as having implemented entry restrictions against Chinese nationals. The choice taken by large numbers of BRI-affiliated countries to impose border checks on Chinese nationals is an indication of the seriousness with which they regard the public health threat posed by the coronavirus outbreak. Some countries made this choice due to a lack of confidence in their own public health systems: among others to cite this factor was Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta (National Public Radio, February 10). Deliveries of material aid to China represent an effort to offset the damage done to their relations with Beijing, but the perception by BRI-affiliated countries of this as an acceptable approach (versus maintaining open access for Chinese nationals) suggests that the soft power and influence accrued to Chinese authorities by the Belt and Road Initiative may not be as great as is widely assumed.

China to the Rescue?

As the announcement of new cases in China has slowed down, PRC authorities have moved to show that the BRI—at least in terms of terra firma project implementation—can get back on track quickly (Xinhua, March 6). However, Beijing has also attempted to engage Belt and Road countries as a provider of public health knowledge: for instance, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs organized a video conference with relevant officials from countries in the “17+1” grouping of Central and Eastern European countries (PRC Foreign Ministry, March 13).

In a potential sign of the PRC government’s future plans for the Belt and Road Initiative, there have been rumors that government-connected scholars have sought to build track-two support for a Beijing-led alternative to the U.N.-affiliated World Health Organization (WHO); however, on March 9 the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced a $20 million donation to the WHO to support anti-coronavirus efforts (Xinhua, March 9). In a phone call with United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, President Xi said that Chinese authorities had shared insights from their experience in fighting COVID-19 with counterparts from other countries, who together with China form a “community of mankind that suffers and succeeds together” (Yidaiyilu.gov.cn, March 13).

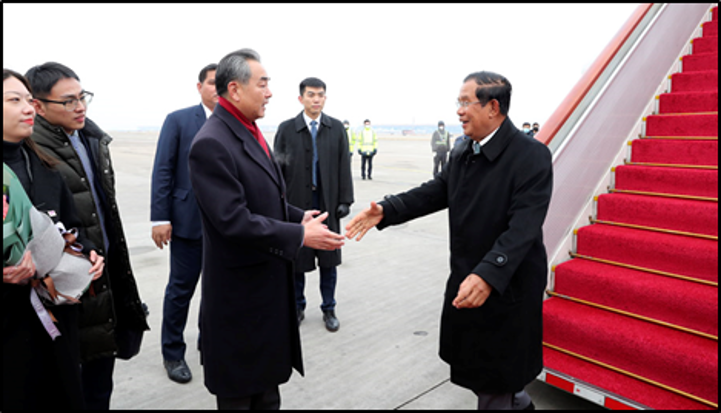

Xi’s remarks followed a statement by the PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which stated that China would (among other points) send medical teams to countries in high need, provide drugs to any countries that need them, and strengthen technological cooperation with the international community (Yidaiyilu.gov.cn, March 12). Likewise, Vice Foreign Minister Ma Zhaoxu told a press conference that China had provided coronavirus-related support to South Korea, Iraq, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka (Xinhua, March 6). The effort to position Beijing as a magnanimous provider of global public goods is not limited to public health: China’s e-commerce marketplaces have been cited by government-linked sources as an avenue that international businesses can use to mitigate the virus-related economic downturn (Yidaiyilu.gov.cn, March 11).

In addition to highlighting the assistance Beijing has provided, Chinese authorities have also sought to paint a contrast with what it describes as efforts by “some in the United States… [who] are trying to shift the blame and politicize humanity’s common challenge by stoking pernicious anti-Chinese sentiments” (Xinhua, March 9). However, whether Beijing’s assistance will make a substantive impact on international opinion remains to be seen.

Conclusion

In a fiery February 12 commentary, the Global Times charged that “it is completely irrational to implement inter-country isolation to prevent the spread of the disease. It is unscientific and also violates the interests of all countries.” While the contagiousness of the coronavirus casts doubts over the scientific foundations of the state tabloid’s claim, it is nonetheless useful as an insight into the reaction of PRC authorities to the widespread imposition of restrictions on the international travel of Chinese nationals. Disappointment in Zhongnanhai is likely to be deepened by the vast sums spent in recent years under the Belt and Road Initiative, aimed at increasing China’s international influence and soft power.

Within the context of the coronavirus outbreak, the payoffs from BRI have been extremely limited: while Ethiopian authorities continue to permit flights to China, as many as 91 of the 115 countries listed by Chinese authorities as Belt and Road “international cooperation partners” have imposed border restrictions on Chinese nationals. Within the context of this crisis, this suggests that the soft power and influence accrued by BRI is not as extensive as others have posited. In that sense, the coronavirus outbreak is much more than what the Global Times has called an “occasional bump in the road” for the Belt and Road Initiative (Global Times, February 19). Nonetheless, messaging from Beijing following the abatement of new cases in the PRC suggests that it will seek to use its response to outbreaks overseas to enhance its international reputation.

Johan van de Ven is a Senior Analyst at RWR Advisory Group, a Washington, D.C.-based consultancy that advises government and private-sector clients on geopolitical risks associated with China and Russia’s international economic activity. He leads RWR’s research and analysis of the Belt and Road Initiative, the centerpiece of foreign policy under Xi Jinping, and also edits the Belt and Road Monitor, RWR’s bi-weekly newsletter.