Mongolia’s Place in China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’

Mongolia’s Place in China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’

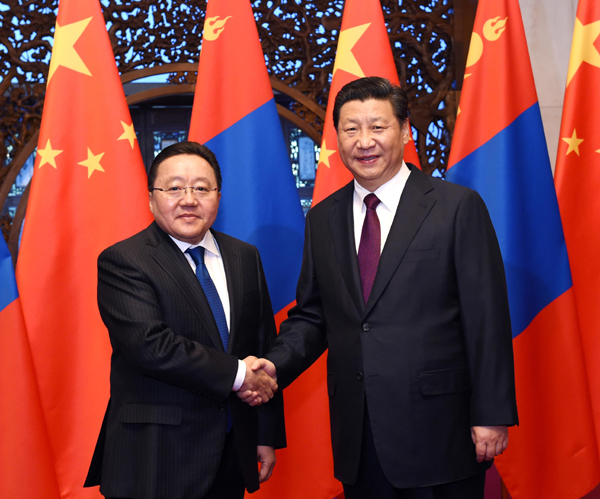

Although the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been active in promoting its ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR) Eurasian and maritime initiative during the last two years, to the north in Mongolia there has been doubt as to how Mongolia can derive economic benefit from this policy. When the OBOR was first announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping, in September 2013, he spoke of reviving Chinese contacts with the Silk Road nations, but he did not mention which nations or which Silk Road time period he was referring to (CCTV, September 7, 2013). The Mongolian Empire’s Silk Road (1206–1400) included China, the Mongolian heartland, and extended into the Korean peninsula and parts of Siberia. However, the OBOR’s lack of explicit inclusion of Mongolia, the Koreas (both North and South) and Japan, caused Mongolian policymakers to believe that this grand Chinese economic and social connectivity concept in a 21st century version of the Silk Road was designed in such a manner as to push Mongolia aside if not to outright exclude it. [1] Although China’s Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region (IMAR) was labelled a vital part of the proposed OBOR transit route, Mongolia feared that its poor rail and road infrastructure could prompt China to develop the concept in such a way as to focus logistics westbound and not to the northeast, as it decided to do with oil and gas pipelines in 2011–2012 (Mongolia Briefing, July 3, 2012). As a result, Mongolia proactively has lobbied both China and, especially, Russia since 2014 about becoming an integral part of growing regional transport networks. After achieving preliminary agreement in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, in September 2014, Mongolia’s role in OBOR-related projects was publicly solidified at the second trilateral meeting of Russia, China and Mongolia, in Ufa, Russia, on July 10. This reassuring clarification also may have been influenced by Mongolian President Tsakhia Elbegdorj’s new foreign policy initiative, announced in Japan in late May, called the “Forum of Asia.”

Chinese Explanation of OBOR’s Connection to Mongolia

At this year’s Boao Forum for Asia (BFA), President Xi discussed OBOR as the central focus for China’s development for Asia and the world. In a document entitled “Visions and Actions on Jointly Building Belt and Road,” issued on March 28—the day of Xi’s speech—various economic, financial, cultural and security aspects were explained. Although this report noted that Harbin would be the focal point for “developing China-Mongolia-Russia” economic corridor, there was little additional explanation (NDRC, March 28). With China’s underdeveloped northeast provincial role in OBOR also not specified and because the jammed ports of Tianjin and Vladivostok are forcing China to find other Pacific deep-water ports open year round to ship its goods to Republic of Korea, Japan and North America, Chinese authorities responded with a development scenario that would link into OBOR.

In May, China’s Vice Premier Zhang Gaoli specifically confirmed Mongolia’s role in its OBOR planning (China Daily, May 28). At the trilateral meeting prior to the Ufa Brazil-Russia-India-China (BRICs) and Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) conference in July, Xi expressed hope that the three countries would connect the Silk road Economic Belt to Mongolia’s “prairie or grassland” road (which Mongols term the “Steppe Road”) and with Russian rail network expansion plans (CCTV, July 10).

This Chinese trilateral economic corridor has two pilot areas. The first connects Erenhot (二连浩特) with Manzhouli (满洲里) in IMAR and Eastern Russia. The second pilot program involves constructing a trade cooperation zone at the Erenhot–Zamiin Uud (Mongolia) border with the first phase in Erenhot scheduled to begin operations in August. The aim is to develop traditional trade, processing trade and e-commerce through improving traffic interconnectivity and facilitating cargo clearance and transportation. Erenhot mayor Luo Qing commented that: “At the next stage we will actively support a special logistic program called ‘Mongolia-Russia Connect,’ so that the traditional trading client can catch up with the development (CCTV, June 8).”

After the Ufa summit, the Chinese media provided additional explanation on OBOR’s connection to the Mongolian region through combining the Silk Road Economic Belt, the Prairie Road and Trans-Eurasian Belt Development to “boost the building of [a] China-Russia-Mongolia economic corridor and promote practical cooperation projects, including railways, roads, energy resources, logistics, transportation and agriculture,” and noting that “The China-Russia-Mongolia economic corridor is the lifeline of the [OBOR] aorta (CCTV, July 15).” [2]

Mongolian Seeks Eurasian Rail and Road Linkages Through ‘Trilateralism’

During the summer of 2014, Mongolian President Elbegdorj welcomed to Ulaanbaatar both Chinese President Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin. During these state visits, he pressed both sides to agree to annual “trilateral” summits, the first of which took place on September 11, 2014, in Dushanbe, Tajikstan (China Brief, September 25, 2014). Since then, Mongolia has promoted the importance of the Chinese-Russian-Mongolian trilateral relationship, particularly in regards to implementing rail and road construction and exploring how to link Central Asian natural gas fields to China and the ROK by transiting Mongolia (President.mn, September 11, 2014). The first-ever Russia-Mongolia-China trilateral deputy foreign minister–level consultations took place in Ulaanbaatar, in late October 2014, followed by a second round in Beijing, on March 23, 2015 (Xinhua, October 30, 2014; Chinese MFA, March 24). The three sides focused on cooperation in fields of politics, economy, local governments, science and technology, people-to-people cultural exchanges, and international affairs, and exchanged views on “formulating a trilateral cooperation roadmap and establishing an economic corridor among China, Russia and Mongolia” (Chinese MFA, March 24).

During the official visit of Mongolian Foreign Minister Lundeg Purevsuren with PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Beijing in April this year, the Chinese reported that there was consensus on connecting China’s Silk Road Economic Belt and Mongolia’s Prairie Road to “elevate and integrate bilateral practical cooperation in economy and trade, and on actively carrying out the medium-term outline for bilateral economic and trade cooperation to realize the target of $10 billion of bilateral trade volume by 2020 (Chinese MFA, April 2).” It was further reported that both sides agreed on accelerating cross-border economic cooperation zone construction and to actively research and sign a bilateral free trade agreement.

However, prior to Purevsuren’s April visit, Mongolia had committed to new road construction toward China as a partial answer to reviving its flagging mineral export trade and specifically increasing copper concentrate tonnage exiting its Rio Tinto–operated mine at Oyu Tolgoi. A tender was announced in March for a survey of the 550-kilometer road from Maanit to Zamiin-Uud (Chinggis Group, April 2). During the April foreign minister discussions, Mongolia agreed to a mega highway project that crosses the country from north to south to link it to Russia and China. This proposal for a fully paved Altanbulag-Ulaanbaatar-Zamiin-Uud highway had been delayed for decades by Mongolian policymakers for national security reasons (China Brief, August 23, 2013). They believed that the Mongolian economy, which has been monopolized by China for the last 15 years, would never overcome this situation if such a road were built, so many promoted an east-west “Millennium” highway across the country instead (Asia Development Bank, 2014). At the opening ceremony at the Sino-Mongolian border at Zamiin Uud in late May, the Chinggis Land Development Group, Mongolian National Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and Mongolian Road Association signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to employ Mongolian companies, increase the number of Mongolian road and construction staff and train Mongol engineers and technicians. It is estimated that 20,000–30,000 temporary jobs and 50,000 jobs in new residential zones will be created during the three-year construction of the entire 990 km highway (GoGoMongolia, May 29).

In the Mongolian capital, on April 9–10, there was a second consultative meeting of deputy ministers of railway and transportation from the three nations. The Mongols began this particular dialogue in December 2013, in Ulaanbaatar, in order to develop trilateral cooperation among the transportation sectors to expand transcontinental railway transportation transiting Mongolia. At the meeting, Chinese, Russian and Mongolian rail authorities confirmed plans to implement railway transit cooperation, improve existing railway freight volumes, research the building of a trilateral transportation logistics company, promote development of railway transport capacity along the Ulaan Ude–Naushki–Sukebaatar–Zamiin Uud-Erenhot-Jining corridor, promote cooperation among railway educational institutions, and support personnel training and scientific research cooperation (Montsame, April 10). However, in all these bilateral and trilateral initiatives there was no explanation of how this cooperation directly related to OBOR.

Forum for Asia

With all the apparent momentum in 2015 toward Mongolian and Chinese cooperation, it is interesting to consider why the Mongols have proposed the establishment of a new Mongolian continental dialogue platform, the Forum of Asia, to build mutual trust and boost regional integration. President Elbegdorj, on May 21, in Tokyo, introduced the concept at the 21st International Conference on the Future of Asia. He suggested that this new platform should promote equal representation of interests of all sovereign nations in Asia, small or big, to guarantee the independence, integrity and development models of all members. In an interview with a Japanese newspaper, he likened it to a small United Nations in Asia, but with equal rights. The Forum could foster the region’s success and overcome economic challenges by focusing on “security, rule of law, the environment, as well as social and economic areas” (Nikkei, May 21). Calling Mongolia an honest broker in dealing with promotion of peace and security in Northeast Asia, Elbegdorj evoked the days of the Mongol Empire when his people “actively engaged with nations near and far in Asia, Europe and the Middle East. It was an era when the Mongols strove to establish a new world order—justice, peace and cooperation in their relations with other states and peoples” (Montsame, May 22).

The Mongolian president never mentioned OBOR. Rather he emphasized his nation’s commitment to meaningfully contribute to the political and economic integration processes in the Asia-Pacific region since there was no single mechanism of regional integration that included all 48 Asian states. The Forum would “ensure the rights of all member states while deterring hegemony and securing equality. It is better to have one common platform for all Asian nations than wrestling one by one in the global arena” (Nikkei, May 21).

Only three weeks later, on June 8, Elbegdorj introduced the concept again in a speech he made to the European Parliament, in Strasbourg, France. Emphasizing that Mongolia’s commitment to international cooperation is strong, he explained that the Forum of Asia hopefully “will serve as a much-needed mechanism to promote regional integration of all sovereign nations in Asia, promoting equal representation of their diverse interests. My government is now working to finalize this concept, and is inviting interested parties to contribute ideas that will aid its realization” (Mongolian MFA, June 9). In this speech, Elbegdorj also mentioned other recent Mongolian-developed initiatives to build regional understanding, such as establishing the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue on North East Asian Security, which he compared to the Helsinki dialogue of Cold War days, and Mongolia’s chairing of the Freedom Online Coalition on May 4–5 to promote access to the Internet for all.

It cannot be a coincidence that Elbegdorj introduced his Forum of Asia during his seventh visit in 26 months with his close friend, Japanese Prime Minister Shinto Abe (Eurasia Daily Monitor, February 20). While not necessarily a competing idea to OBOR, the Forum explicitly invites all Asian nations to participate, and its announcement first in Tokyo cannot have been ignored by Chinese authorities, even though the speech received no Chinese media coverage. Back in Mongolia, Elbegdorj’s Forum of Asia concept came as a complete surprise to the researchers in Mongolia’s leading Asian and strategic studies institutions. [3] Usually such new proposals are vetted with Mongolia’s research community before they are publicly announced. In June, Mongolian researchers privately stated that they have done little analysis so far of China’s OBOR policy, except for some reports narrowly circulated in intelligence circles, because they still did not believe Mongolia was included in China’s OBOR. Of further interest was the fact that a leading Mongolian parliamentarian who is involved in developing Mongolia’s China policy declined to comment when specifically asked if the Forum was a Mongolian response to China’s OBOR. [4] However, at the Ulaanbaatar Dialogue for North East Asian Security’s second meeting in Ulaanbaatar, on June 25–26, Chinese high-ranking officials from the China Institute for International Strategic Studies (CIISS), in response to direct questions about Mongolia and OBOR, provocatively claimed that Mongolia and other nations, such as Japan and even the United States, could “join,” if they wished. [5]

Conclusion

To date, Chinese media has not commented in the media on Mongolia’s “Forum of Asia” concept, although it has supported the Mongolian transportation strategy of “trilateralism” within the greater context of OBOR. China’s lack of clear response to Mongolia’s new concept of Asian regional integration may indicate that the Chinese leadership is still considering its response and thus was not willing to publicly comment when it signed four new agreements at Ufa with Mongolia and Russia to establish the legal framework for future economic cooperation “to enhance trade and economic partnership, to increase transit transportation and to explore the opportunity to establish a joint railway transportation, and logistics company” (InfoMongolia, July 10). As we enter into the last two years of Elbegdorj’s Presidency, we should expect more ambitious initiatives to elevate the image of Mongolia on the global stage because he is determined that his country have a strong voice on the Asian continent. Still, it is important to recognize that Mongolia with its “Forum of Asia” is not necessarily rejecting the OBOR, but seeking more guarantees from China that it will benefit from inclusion and not be ignored in Asian regional infrastructure.

Notes

1. Some Chinese scholars, including Xu Shanda (noted tax economist and former member of Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference) and Jin Ling (a Sino-EU specialist at CIIS), as well as foreign commentators have compared OBOR to the post-World War II Marshall Plan, despite official Chinese denials (China Institute of International Studies (CIIS), CIIS, June 11, 2015; The Diplomat, November 6, 2014).

2. According to CNTV, the Mongolian Prairie Road program consists of five projects with a total investment worth about $50 billion. Its projects include a 997-kilometer highway connecting China and Russia, a 1,100-kilometer electrified railway, and the extension of trans-Mongolian railways, gas and oil pipelines.

3. Private interviews in June in Ulaanbaatar with various Mongolian specialists on China in government-related think tanks.

4. Private interview of author with this Mongolian parliamentarian.

5. Author attended the UB Dialogue Conference II (June 25–26) and was one of several people who directly asked Chinese participants this question.