Mustafa al-Sharkasi: the Misratan Leader of the Benghazi Defense Brigades

Mustafa al-Sharkasi: the Misratan Leader of the Benghazi Defense Brigades

Introduction

In the past few months, the conflict over the control of oil resources in Libya has deepened further, particularly after the takeover of the largest oil terminals of the Oil Crescent by the Libyan National Army (LNA) forces led by the controversial Libyan general Khalifa Haftar (Maghreb Emergent, March 10). One of the key forces in this conflict, and to date possibly the greatest enemy of Haftar, is the Benghazi Defense Brigade (BDB), also known as the Saraya Defend Benghazi. The stated aim of this Islamist-oriented militia, which was formed in mid-2016, is to bring the displaced people of Benghazi back to their homes.

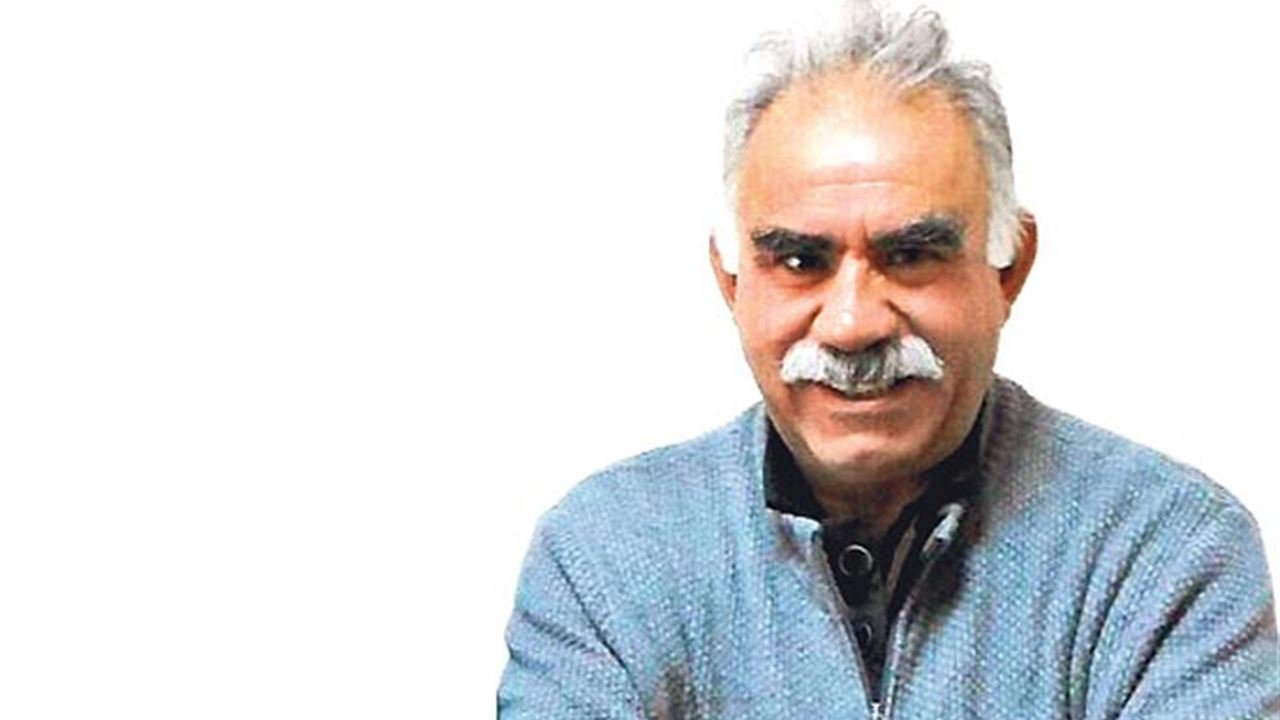

One of the key leaders of this organization is Mustafa al-Sharkasi. A prominent revolutionary from the city of Misrata, al-Sharkasi used to be the spokesperson for the air force of the National Salvation Government (NSG) army in Tripoli, the government associated with the General National Congress (GNC), the Islamist-dominated parliament elected in 2012. However, he has recently emerged as one of the key leaders and public faces of the BDB, as well as one of its top field commanders. He is also considered close to the Grand Mufti of Libya, Sadik al-Ghariani, and understanding his role is crucial to shedding new light on some of the dynamics of the Libyan conflicts.

Benghazi Defense Brigade

The BDB is an Islamic-oriented militia that first emerged in mid-2016 when it launched the Operation Volcano Rage to regain control of Benghazi. Also linked to the Benghazi Revolutionaries Shura Council, the BDB, in its initial statement, said that the Benghazi Revolutionaries group had launched an operation to defend Benghazi and support the Benghazi Shura Council as well as Ajdabia revolutionaries. It stressed that it was not linked to any party or organization, be it local or foreign, and that all of its fighters are Libyan. In the statement, the BDB openly criticized Haftar, claiming that his followers should return to their senses and “to the February revolution track after the truth of the Dignity Operation had unfolded” (Libya Observer, June 2, 2016). These fighters were originally located at the Jufra airbase near Hun, an area Haftar’s forces often targeted. However, in April 2017, the group moved to another location, which was kept secret, and they handed control of the airbase over to the general chief of staff of the GNA-aligned Libyan army (Libya Herald, April 9).

Unlike the LNA, the BDB is not organized around a single strongman. Rather, there are several prominent militants with influence inside the group other than al-Sharkasi: al-Sa’adi al-Nawfali of the Adjdabiya Shura Council; Ziyad Balham, the commander of Benghazi’s Omar al-Mukhtar Brigade — named after the anti-Italian colonial hero; and Ismail al-Salabi, chief of the Rafallah Sahati militia, brother of Ali Muhammad al-Salabiand, one of the key leaders of the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood (Aberfoyle Security, July 2016).

Within the somewhat decentralized leadership structure of the BDB, Mustafa al-Sharkasi is emerging as one of the key leaders of the organization. Often depicted as a leader at the center of BDB whose public and political role is on the rise, al-Sharkasi is seen as dictating the strategic agenda of the organization and its moves on the battlefield, as well as holding influence in the group through his ideological positions and personal relationships.

The Emergence of al-Sharkasi: Conflict in the Oil Crescent

Recently, al-Sharkasi made headlines after the eruption of the conflict pitting the group he now leads, the BDB, against the Haftar-led LNA forces. Since May 2014 — after launching a military operation called “Dignity” to destroy Islamist forces in eastern Libya, mostly in Benghazi and Derna — Haftar has progressively risen as a key politico-military player in Libya. This conflict has been one of the key elements that set the conditions for Libya to split into two competing governments — now three, considering the resurgence of the NSG under Khalifa Ghwell.

Against this backdrop, the conflict for control of oil resources has recently regained momentum. In September 2016, Haftar’s forces seized control of the largest oil terminals of the so-called Oil Crescent — Ras Lanuf, Es Sider, Zueitina and Brega — displacing units of the Petrol Facilities Guard (PFG) led by the controversial and very volatile Ibrahim Jadhran. This move was condemned by external actors (al-Arabiya, Sept 13, 2016), although some misleadingly thought that Haftar’s takeover could lead to a de-escalation of the Libyan conflict (al-Monitor, Sept 20, 2016). Indeed, this situation of apparent calm lasted only a few months. In early March, the BDB launched a massive attack against the LNA forces of General Khalifa Haftar. Nine men were killed, and the BDB captured five cities and two of Libya’s largest export terminals, Es Sider and Ras Lanuf (al-Jazeera, March 4). However, this lasted only a few days: in mid-March, Haftar regained control of Es Sidra and Ras Lanuf (al-Jazeera, March 14). Haftar reportedly enjoyed the support of foreign air power in these efforts, with the BDB openly accusing Haftar of being backed by the Egyptian air force. (Libya Observer, March 16).

The Benghazi Defense Brigade, al-Sharkasi and a Controversial Ideology

In the wake of the recent fighting against the LNA forces, the BDB outlined its political vision in Statement No. 19. Stressing that the clear majority of its forces are from Benghazi and wider Cyrenaica, it says it aims to keep alive the heritage of the “17th February revolution against injustice and tyranny.” The BDB continues to stress that its members have no party, political or ideological affiliations, and the ultimate goal is merely humanitarian — to allow people unjustly displaced from their homes to return (Libya Observer, March 12).

The BDB has often reiterated its local nature and absence of links with any other organizations, either national or foreign. The group’s sole religious reference is to the Libyan Fatwa House (Dar al-Ift), headed by Libyan Grand Mufti al-Ghariani. It frequently seeks to clarify this in an effort to dismiss accusations of links with foreign and national jihadist groups. For instance, the “new” state news agency that the government in Bayda created in 2014 as an alternative to the LANA (Libyan News Agency, formerly known as Jamahiriya agency) (Reuters, Oct 27, 2014; ADN Kronos, October 27, 2014), published an extensive article accusing the BDB and Mustafa al-Sharkasi of sharing deep connections with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Ansar al-Sharia in Libya. Al-Sharkasi was also accused of having significant links with major jihadist fighters belonging to these two organizations (LANA [Bayda], March 8).

While al-Sharkasi and the BDB work to deny links with jihadist groups, their link with the Grand Mufti is contentious in its own right. Al-Ghariani has frequently created controversy through his statements. For example, at the peak of the fight to free Sirte from IS, he said that the real enemy “was Haftar, and not IS” (Libya Herald, May 12, 2016). Al-Ghariani went so far as to demand that Misratan forces and their allies who were fighting the group in Sirte not move beyond Abu Grain to fight IS. However, his demand was ignored, and the forces continued their action. Just a few months before this incident, however, al-Ghariani said that IS was Libyan “greatest cancer,” even calling upon Haftar to join forces with Misratan forces to defeat the group (Libya Herald, Aug 15, 2015). And despite the fact that he is still associated with the GNA, al-Ghariani recently criticized the government led by Al-Sarraj, saying that he and Haftar are “two faces of the same coin” (Libya Herald, Jan 4, 2017).

Despite his volatility, al-Ghariani is still considered one of the fiercest enemies of Haftar within the country. He has often characterized Haftar as an “infidel.” This opposition brings al-Sharkasi very close to al-Ghariani. Indeed, one of the key elements characterizing al-Sharkasi’s approach is his fierce opposition to Haftar. At the start of the conflict, al-Sharkasi clearly stated that their aim was to “break Haftar’s nose in Benghazi” (Libya Akhbar, June 29, 2016). This opposition is also reflected in the BDB’s attitude toward Haftar: the group has recently ruled out the possibility of including Haftar in a possible reconciliation dialogue, denouncing the attempts of the House of Representatives (HoR) to bring him in (Libya Observer, April 4).

Al-Sharkasi aims at achieving this goal by boosting the BDB’s military capacities. Recently, al-Sharkasi noted that the BDB has increased its military capacity, and now it has weaponry that can shoot down enemies’ warplanes. Moreover, in an interview released after the BDB’s defeat in March 2017, he said that the group is working to build up its military capacities further, also noting that many new fighters from different parts of the country are joining the organization, as they share the aims of defeating the enemies of the revolution (Noon Post, April 1, 2017; al-Sharq al-Awsaat, March 7).

A Misratan for Benghazi

One of the most interesting aspects of al-Sharkasi’s rise is that a militiaman from Misrata, which is located in western Libya, is now one of the key leaders of a group of fighters from Benghazi and the east of Libya. This is evidence of the increasing complexity of the Libyan political and strategic landscape. The idea that Libyans remain primarily divided along the historical boundaries of the Ottoman provinces — Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan — is no longer viable, as alliances run along other geopolitical lines.

On the other hand, the fact that a Misratan is leading this group is further confirmation of the growing influence that the Misratans have on the Libyan political scene. This rise was triggered by the dominant role that Misratan militias played in the revolution against Qaddafi. However, the significant Islamist characterization of the BDB has promoted the idea that all Misratan militias are Islamist, rhetoric supported by Haftar and his allies. The picture is far more complex. Misratan militias are diverse internally, in terms of political visions and ideologies, but the geographical link and the convergence of strategic interest has allowed them to keep working together. Al-Sharkasi clearly represents a political area closer, in ideological and strategic terms, to the Libyan Islamist world, and his political convergence with the Libyan Grand Mufti proves this. That said, this does not imply that all the militias from Misrata are Islamist and that, because the al-Sharkasi, the BDB and the Misratans support the GNA, Islamists have hijacked the UN-backed government and dictate its agenda.

Conclusion

Mustafa al-Sharkasi is now one of the key leaders of the BDB. His role has increased over the past few months, and he is now one of the most recognizable public faces of the BDB. His presence as a Misratan at the head of a group primarily focused on Benghazi is a further example of the rising influence of Misratans in Libya. A fierce enemy of Haftar, he is very close to the positions of Libya’s Grand Mufti, al-Ghariani. The latter is considered to be very radical and connected to jihadist groups, although his declarations have often showed a certain degree of political volatility, and many of them were dictated by tactical needs more than strategic aims and views. However, there have been repeated accusations that al-Sharkasi and the BDB are connected to radical Islamist organizations. While he is clearly linked to Islamist organizations, these connections do not mean that he, or the Misratans, are necessarily connected to jihadist groups. The situation inside the BDB is complex: there are groups with different political sensibilities, some closer to more radical Salafi ideas, others closer to a less extreme view of political Islam and the process of reconciliation within Libya.

Looking ahead, al-Sharkasi will continue his anti-Haftar campaign, and has reiterated in various media interviews that he is working to build up the military capacities of the BDB, accessing more sophisticated weapons and strengthening the group’s manpower. Under his guidance, the BDB will continue to represent the first line on the ground against Haftar’s forces. Although Libyan politics is very fluid, and alliances can shift quickly, it is likely that al-Sharkasi, the BDB and the Misratans will continue to fight against Haftar’s inclusion in any political dialogue. This resistance alone is likely to play a key role prolonging the Libyan conflict in the coming months.