New Hopes for Shorter Caspian-Black Sea Canal Spark Growing Opposition

New Hopes for Shorter Caspian-Black Sea Canal Spark Growing Opposition

The hopes of China and some Central Asian countries for the construction of a new canal between the Caspian and the Black Sea have sparked serious ethnic and environmental opposition even before the first spade of ground is turned. The project has its roots in the megaprojects of the Stalinist Soviet era—the types of massive “public works” that have experienced a comeback under current President Vladimir Putin. The existing waterways in this region lack the capacity to be economically significant. However, any canal large enough to compete with alternative routes would not only be massively expensive—costing at least $10 billion—but would also have a deleterious impact on the environment. Therefore, inhabitants of areas through which this canal would pass, in particular the newly active Kalmyk nation and its political leadership, express increasing opposition to this initiative. Many Russian environmental activists feel the same way. But some in the Kremlin may not: giant projects like this one open the way for massive diversions of public funds into the hands of its oligarch allies.

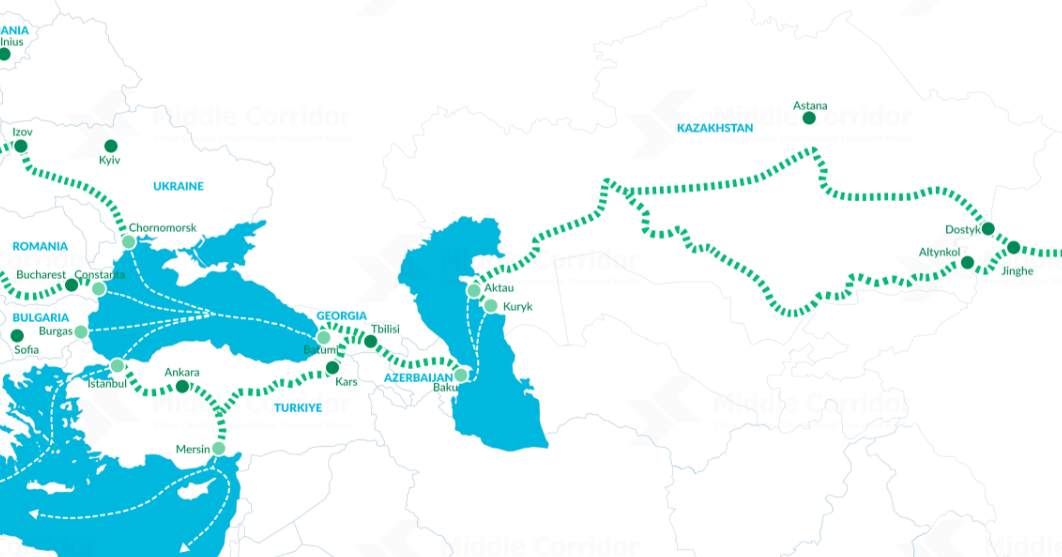

The proposed so-called “Eurasia” shipping channel, would expand and connect a series of rivers and waterways across the northern territories of the North Caucasus. The eastern end of the route would open to the Caspian along the Kuma River, at the border between Dagestan and Kalmykia; the western end would open into the Taganrog (Tahanrih) Bay, in the Sea of Azov, which itself connects to the Black Sea via the Kerch Strait. As a straighter and more direct riverine transit corridor than the pre-existing Caspian–Black Sea link—the more northerly, 17-lock Volga-Don Canal—the 700-kilometer-long Eurasia canal would shave approximately 1,000 kilometers off the Volga-Don route and consist of only 6 locks. Additionally, the Eurasia canal could handle larger cargo vessels (10,000 tons, with a draft of up to 10 meters) compared to the Volga-Don Canal (5,000 tons, 5 meter draft), promising annual shipping capacities of as much 45 million tons (Zonakz.net, July 12, 2018; The Brussels Times, June 1, 2018; see EDM, October 1, 2010).

The leading advocates of this project today are Kazakhstani President Nursultan Nazarbayev and the Chinese government. Nazarbayev says that such a canal would radically expand Kazakhstan’s foreign trade with Europe, especially bulk cargoes like coal. For his country, he suggests, such a canal could make all the difference between becoming an economic star or fading into a backwater with few prospects beyond its immediate region. Other Central Asian countries are interested as well but less focused on this project than Kazakhstan (Total.kz, July 21).

The Chinese government is also supportive; yet, for Beijing, such a canal is not essential but rather an additional insurance policy should problems in the Indian Ocean restrict its ability to send most of its goods to European markets by sea. As analysts in Kazakhstan and Russia note, China does not want to rely on any single route and, therefore, promotes a band of links between itself and the West. A large new canal connecting Central Asia and Europe via the Caspian and Black Sea could be an essential part of that broader strategy (Zonakz.net, July 12; Casp-geo.ru, August 3).

The Russian government is at present less supportive. On the one hand, at least some in Moscow do not want to give Kazakhstan and other Central Asian countries yet another way to reach Europe without passing through European (northwestern) Russia, especially if the central Russian government would likely have to bear much of the cost for any canal. Indeed, financing issues had blocked earlier plans for such a project in the 1930s. And on the other hand, far more Russian officials today are worried about the environmental consequences as well as the political consequences that they might face if they ignored them. The reason for that is not difficult to discern: In the early 1980s, Moscow’s push for Siberian river diversion broadly undermined Russian support for the Soviet government and ultimately forced the authorities to drop that large, expensive and environmentally disastrous project.

Analysts from both Russia and Kazakhstan have been playing to those fears. They point out that while a new canal would expand trade opportunities, it would be extremely expensive and would inflict environmental devastation on the Russian North Caucasus, a region already suffering from water shortages. To make a larger canal function, ever more water would have to be diverted from other purposes, including providing water for human needs. Some of these analysts are describing the canal plan as “idiotic” or using even more damning terms (Zonakz.net, July 12).

They are joined in their opposition by ethnic groups living along the route, including most prominently the Kalmyks, through whose territory the new canal would pass. In Kalmykia, not only the expert community but also the government have come out against the plan, arguing that it could destroy the economic and social welfare foundations of the population. Their objections have become so loud that they have even attracted the attention of the national Russian media (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, August 1).

This new opposition and Russian memories of the Siberian river diversion case would seem to be enough to kill this project. But there is a compelling reason not to write it off just yet: the Putin government’s proclivity for engaging in giant projects like the recently completed bridge to Crimea or the just-begun bridge to Sakhalin Island. Illustratively, the Kremlin is engaged in these megaprojects even as budgetary stringencies force it to cut back on more banal but important services like hospitals, schools and pensions. Putin clearly hopes he will achieve a boost in support from Russians as a result of such enterprises, which play to the notion that the Russian nation can overcome even the most difficult geographic tasks. Moreover, he knows—as anti-corruption activists have documented, from the Sochi Olympiad (see EDM, February 10, 2014) to the World Cup (RFE/RL, June 15, 2018) to the Kerch Bridge (Crimerussia.com, July 26, 2016)—such projects give ample opportunity to divert funds to his friends and, thus, maintain their support.

Taken together, all this means Moscow will likely begin the project, possibly with major allocations of funds that can be handed out to the oligarchs. But the government may ultimately back off if environmental and local opposition grows too strong.