Parsing China’s Policy Toward Iran

Parsing China’s Policy Toward Iran

On November 8th, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) released a report that said Iran appeared to be carrying out research activities “relevant to the development of a nuclear weapon” [1]. The report caused a temporary reemergence of the Iranian nuclear issue to the fore international politics, and once again China’s found its policy interests stuck between Iran and the West. Now that the dust has settled, China appears to have weathered this mini-crisis fairly well. Beijing neither had to break ties with Tehran, nor was it forced to apply new sanctions. Western countries have adopted some sanctions of their own, but Chinese companies invested in Iran should be able to circumvent them.

China’s response to the latest Iranian nuclear issue is best understood by considering Beijing’s four core strategies regarding Iran: (1) non-proliferation; (2) minimize sanctions to avert war or regime change; (3) influence but not annoy Washington; and (4) secure energy and economic opportunities. The hierarchy of these policies sometimes varies depending on changing circumstances. Furthermore, since some of these goals are in conflict, at least in the short run, Chinese policymakers also must choose among them.

Avoid Nuclear Proliferation Dominoes

Chinese officials do not want Iran to acquire a nuclear arsenal. Tehran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons could set off a proliferation wave and increase the risk of a devastating war in a region that supplies half of China’s oil. Chinese officials repeatedly have made clear their frustration at Iran’s stubborn refusal to meet UN Security Council (UNSC) demands to suspend its nuclear enrichment program, or stop activities that could contribute to Iran’s developing nuclear weapons, until Tehran makes its nuclear work more transparent to the IAEA. In 2010, after difficult negotiations, the Chinese delegation to the UNSC voted in favor of four rounds of economic sanctions, including some rather severe ones.

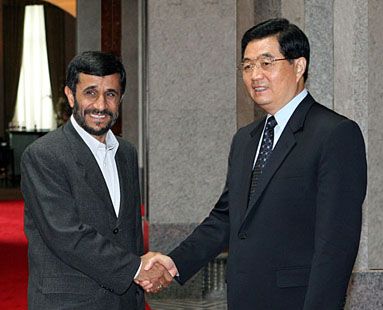

This message also has been passed at the highest levels. Chinese President Hu Jintao met with Iranian President Ahmadinejad shortly before the August 2007 leadership summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). Hu urged “the Iranian side to size up the current situation and show certain flexibility in its efforts to properly address the remaining problems so as to ensure the issue to go forward in a correct direction”(Xinhua, August 16, 2007). The Chinese repeated this position during the November crisis over Iran’s nuclear program driven by the IAEA report. Noting Iran’s statement that it sought to clarify any IAEA concerns, Chinese officials urged Tehran to address agency concerns about military dimensions to its program. Nonetheless, Chinese officials prefer that other countries, especially the United States, bear the economic and diplomatic costs of keeping nuclear weapons out of the hands of Iran and other potential nuclear aspirants.

The Chinese government always defends Iran’s right to pursue nuclear activities for peaceful purposes, such as civilian energy production [2]. For example Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi said, “The right of NPT signatories to peaceful use of nuclear energy must be truly respected and upheld, and this right should not be compromised under the excuse of non-proliferation” [3].

Minimal Sanctions to Avoid War or Regime Change

Chinese policymakers do not oppose Iran’s nonproliferation program because they believe that Iran would threaten to use nuclear weapons against China. Their main fear is that Iran’s nuclear program will increase the risk of war in the Middle East, the source of about half of China’s imported oil. Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei told reporters last month that, "China opposes the use of force or the threat of the use of force in international affairs,” especially in the Gulf region since “avoiding any new upheaval in the Middle East is extremely important" (Reuters, November 4).

One possible cause of war is a preemptive attack of Iran by Israel or the United States. In another scenario Iran, emboldened by its nuclear shield, might act aggressively against its oil-rich neighbors in the Gulf. Perhaps the worst scenario would see Iran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons prompting its neighbors to acquire their own nuclear deterrent, leading to a nuclear arms race and, through spiraling fears or miscalculation, escalation to a nuclear war. These scenarios—even short of war—could disrupt oil deliveries to China and considerably raise the costs of China’s energy imports. The 2011 Libyan War gave the Chinese a foreboding of all the complications that could arise from a war in one of their minor oil suppliers.

China has invested heavily in developing strategic and economic ties with Iran. Chinese officials may want to the Iranian regime to change its behavior regarding its suspicious nuclear activities, but they fear regime change in Tehran. The 2009 protests made China aware that it could lose its investments if the opposition ever comes to power in Tehran. New Iranian leaders would not view past Chinese backing for Iran’s authoritarian clerical regime kindly. Chinese interests would suffer even if a new government eschewed a punitive policy and simply reconciled Iran with the West by agreeing to make its nuclear programs more transparent and more constrained. Some Iranian businesses would naturally gravitate toward Western partners, undermining China’s monopoly position. Additionally, the end of active confrontation between Iran and the West would allow U.S. diplomacy and military power to refocus elsewhere—probably including the Asia Pacific, which has received a recent boost in U.S. diplomatic and military resources. Beijing also could lose its Iran card since Washington would no longer need China’s help to constrain Iran, depriving Beijing of the implicit threat of supporting an anti-U.S. government in Tehran if the United States sold more arms to Taiwan.

Chinese policymakers want to dissuade Iranian leaders from taking provocative actions and instead show more flexibility regarding their nuclear program. Even more, Chinese policymakers oppose the use of force against Iran’s leaders or coercive sanctions. Chinese analysts suspect these measures are aimed at overthrowing the Iranian regime by encouraging a popular revolution [4].

Another reason Chinese officials oppose Iran’s nuclear policies is that its expansive scope and suspicious nature leads Western countries to impose economic sanctions. These sanctions often impede China’s economic ties with Iran since they would penalize the kind of business deals some Chinese firms would like to make with Iran.

To avert such sanctions, Chinese diplomats try to keep the Iran issue inside the IAEA rather than having the Agency Board refer the case to the UNSC, which can impose sanctions and adopt other measures to enforce compliance with the NPT.

In November, Cheng Jingye, China’s representative to the IAEA and other international organizations in Vienna, told the agency’s Board of Governors that sanctions or military action would simply make the current problem worse. Cheng stated the focus should be on achieving a peaceful solution through dialogue, especially through the P5+1 mechanism that included China, the other UN Security Council members (UNSC), Germany and Iran (Xinhua, November 18).

There is however a major countervailing consideration. If Chinese policymakers block all sanctions in the IAEA, or when the agency refers the case to the UNSC, then they have encouraged Western powers to act alone. China may need to agree to some punitive measures or other UN action to keep the UNSC the main institutional player on the Iran nuclear issue. Within the UNSC, China enjoys the unique privilege of being able to veto U.S. and other countries’ policies toward Iran. If decisions are taken elsewhere, such as NATO or the EU, or unilaterally by Washington, than Beijing’s influence is diminished. Chinese diplomats would accept some UN sanctions to avert more severe unilateral Western ones that inflict greater harm of Chinese business interests, which China can normally protect from UN measures.

The Chinese have attacked the United States for applying sanctions to Chinese entities dealing with Iranian entities as an illegal extraterritorial application of U.S. domestic law and an infringement of China’s sovereignty (Xinhua, December 29, 2009). More recently, the Chinese government attacked the 2010 Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act and related EU sanctions that were adopted after the UNSC agreed to more limited sanctions in June. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs complained that, “Not long ago, the U.N. Security Council approved Resolution 1929 concerning Iran’s nuclear issue. China believes that all nations should fully, seriously, and correctly enforce this Security Council resolution, and avoid interpreting it as one pleases in order to expand the Security Council’s sanctions” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, July 6, 2010). Chinese representatives made the same complaints about the sanctions adopted by Britain, Canada, and the United States on November 21.

Influence but Do Not Overly Annoy Washington

Chinese policymakers consider the United States the key player on the Iran issue. They see Washington as having considerable influence over the Iran policies of the EU, Japan and South Korea. They do not believe Israel would launch a military attack against Iran without U.S. approval and support. So, Chinese policymakers direct many of their lobbying efforts concerning Iran toward Washington.

Chinese strategists recognize China’s ties with the United States are much more important than those with Iran. China seeks to avoid directly confronting the United States. While Iranian officials like to boast of their close relations with China, the Chinese media and government are much more reticent when discussing their ties with Iran. In addition, Chinese leaders have avoided appearing too close to Mahmud Ahmadinejad, given the Iranian president’s unpopularity. When he visited the Shanghai World Expo in June 2010, Chinese officials conspicuously declined to meet him.

Chinese representatives also make clear that they are uncomfortable with Iran’s confrontational policies toward the West, which have sometimes embarrassed Beijing, as when Iranian Revolutionary Guards supplied Chinese-made weapons to the anti-American insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is doubtful that Chinese political leaders—already straining to manage North Korea—want to tie their policies to a volatile, unpredictable, prickly and hard to control regime.

China prefers to claim multilateral support for its position. Beijing also does not want to be seen by Washington and others as the main obstacle to Western policies, and as Iran’s sole great power patron. Especially when negotiating UNSC resolutions, Chinese diplomats try to let Russia, which shares many of Beijing’s goals regarding Iran, assume the lead in resisting Western sanctions, while pressing Iran to make concessions regarding its nuclear program. When Moscow declines to veto an anti-Iranian resolution or sanctions, the Chinese delegation will typically abstain rather than stand out as the sole veto to the proposed measures. Normally Russia and China stand together on the Iran issue in the UN and the IAEA, so the Western powers compromise to obtain a joint statement and then adopt additional unilateral measures on their own.

In the latest crisis, Chinese press quoted Russian opposition to proposed sanctions or airstrikes, as well as Russian criticism of the IAEA for releasing a provocative report that contained little new information at a time when Iran had agreed to negotiate all issues in dispute with the agency (China Daily, November 11). Chinese sources confirm Russian reports that Chinese and Russian officials jointly lobbied the IAEA against issuing its draft report [4].

Energy and Economics

China’s desire to secure Iranian oil and develop commercial ties with Tehran has become an increasingly important priority. Chinese-Iranian economic ties have soared in recent years. China regularly imports some 10 to 15 percent of its oil from Iran. China has become the leading investor and trade partner of Iran, surpassing European countries and staying ahead of Russian and Indian business enterprises. Chinese firms have helped modernize Iran’s energy industry and transportation infrastructure, including investing in highways, railroads and Tehran’s Metro system. China extracts other natural resources such as coal, copper, and aluminum. China refutes the notion that they are doing anything wrong in pursuing economic opportunities in Iran. Chinese officials have defended their country’s trade with Iran as normal commercial relations that do not harm the interests of other countries or violate UNSC-authorized sanctions (Associated Press, November 11).

Despite their shared goal of preventing Iran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons, Chinese diplomats have resisted American efforts to induce Beijing to pressure Tehran into making more concessions on the nuclear issue (Financial Times, May 11, 2006). Due to hard bargaining, China has managed to exempt their main economic interests Iran from UN economic sanctions. By visibly fighting against the sanctions, they have helped persuade Tehran that China is a reluctant to impose sanctions and that Iran’s wrath should fall elsewhere.

Conclusion

Iran is not a vital Chinese national interest in the way it is for many Western governments. China’s Iran policy reflects the push and pull of other factors, which can include energy, economic, diplomatic and nonproliferation considerations. Iran’s lesser importance compared to Taiwan, Tibet and other vital interests means that Chinese entities can adopt diverging approaches toward Iran. Chinese diplomats can seek to reassure Western governments about their support for preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, PLA military strategists can fantasize of forming an anti-U.S. alliance with Tehran that would give China maritime bases in the Persian Gulf and Chinese firms can focus on making money.

Chinese behavior regarding Iran is bounded. Beijing clearly opposes the extreme outcomes of Iran’s obtaining nuclear weapons or the use of force by Israel or the United States. Furthermore, Beijing wants to see a change in the behavior of the regime, but not regime change. Chinese officials oppose military strikes against Iran or harsh sanctions that could threaten the regime’s existence. Excluding these extreme outcomes, China pursues a flexible policy toward Iran. Beijing adopts a harder line when confronted by greater U.S. or other Western pressure. Otherwise, China’s default position is to exploit the strategic and commercial opportunities created by tensions between Iran and the West while discouraging a military confrontation.

Notes:

-

“Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran,” November 8, 2011. https://www.iaea.org/Publications/Documents/Board/2011/gov2011-65.pdf

-

John Calabrese, “China and Iran: Mismatched Partners,” Jamestown Foundation Occasional Paper, August 2006.

-

“Address by H.E. Yang Jiechi Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China At the Conference on Disarmament,” Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations Office at Geneva and other International Organizations in Switzerland, August 12, 2009, available online at https://www.china-un.ch/eng/hom/t578030.htm.

-

Yun Sun, “Iran and International Pressure: An Assessment of Multilateral Efforts to Impede Iran’s Nuclear Program,” Presentation at the Brookings Institution, November 22, 2011.

-

Simone van Nieuwenhuizen, “The IAEA Iran report: China’s manoeuvres” Lowy Institute, November 10, 2011; Russian Report: “RF I KNR prizyvayut MAGATE ne publikovat’ sekretnye dannye po iranskoy yadernoy programme” [Russian Federation calls on IAEA not to publish its secret information regarding Iran’s nuclear program] Iran News, October 25, 2011, <https://www.iran.ru/rus/news_iran.php?act=news_by_id&_n=1&news_id=76232>.