Recent Trends in Sino-Israeli Relations Bely Lasting Warm Ties

Publication: China Brief Volume: 21 Issue: 15

By:

Introduction

On May 19, the Israeli Embassy in China protested what it called “blatant anti-Semitism” on a Chinese international news program, after the CGTN broadcaster Zheng Junfeng (郑俊峰) openly wondered whether the U.S. position toward Israel was the result of the influence of “wealthy Jews in the U.S.” and pro-Israeli lobbies (Haaretz, May 19; World Journal, May 19). Just two days before, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi used China’s position as chair of the United Nations (UN) Security Council to propose a four-point plan for peace between Israel and Palestine, which called for negotiations and a cease-fire but also criticized Israel in particular for its lack of restraint (Xinhua, May 16). More recently, during a state visit to Egypt on July 18, Wang proposed China’s direct involvement as a neutral negotiator and invited both sides to come to negotiate directly in Beijing under the banner of a UN-led global peace conference with the participation of all the Security Council permanent members and “stakeholders in the Middle East peace process” (Xinhua, July 19).

Traditionally, Israel has been reluctant to act overtly against Chinese interests. On June 23, Israel for the first time criticized human rights violations in Xinjiang, signing a joint letter to the UN Human Rights Council, but only at the request of the United States and after a debate in which several officials “raised concerns about backlash from Beijing” (Jerusalem Post, June 23). The Israeli foreign ministry spokesperson Lior Hayat confirmed that Israel had supported the statement but gave no further details (Times of Israel, June 23). Other than this, Israel has appeared largely unwilling to rock the boat with its third largest trading partner and top source of imports. By the same token, China seems unwilling to move beyond critical rhetoric and lofty proposals that merely repeat the international consensus on a two-state solution. It has not acted in any way to pressure Israel to modify its behavior in Palestine or come to the negotiating table, despite having extensive economic and political ties that could be used as leverage.

The Triangular U.S.-China-Israel Relationship

Multiple media reports have indicated that Israel is under pressure from the United States to temper its enthusiasm for good relations with China. (Times of Israel, June 23; Financial Times, May 13, 2020). Most recently, Washington pushed back against Chinese participation in Israeli 5G networks and Chinese involvement in the expansion of the Haifa port, citing espionage and surveillance concerns. At a recent lecture at Bar-Ilan University, ex-Mossad chief Yossi Cohen pushed back against this assessment, saying “I do not understand what the Americans want from China. If anyone understands, they should explain it to me. China isn’t against us and is not our enemy.” Another senior government source told Haaretz that such concerns are not taken seriously: “If they [China] want to gather intelligence, they can simply rent an apartment in Haifa instead of investing in ownership of a port” (Haaretz, June 8).

China and Israel have a long history of quietly pursuing positive relations despite various forces demanding a different public face.[1] China maintained an anti-Zionist stance throughout most of the Cold War as part of its diplomatic strategy to win votes to oust Taiwan at the UN, despite Israeli overtures. Israel was the first country in the Middle East to recognize the PRC as the legitimate government of China in 1950, but anti-Zionist rhetoric persisted until the 1980s, and relations were not officially established until 1992. To this day, China still uses pro-Palestinian rhetoric to forge stronger relations with Arab states, but its criticism is far more tempered and tends to place Palestinian and Israeli security concerns on equal footing. At the same time, it has developed a dynamic, multi-faceted relationship with Israel that makes it unlikely that either side will abandon efforts to maintain some level of partnership.

Economic Ties

China and Israel have seen a dramatic expansion of economic ties since diplomatic relations were normalized. In the past 28 years, the bilateral trade relationship has grown from around $50 million to just under $10 billion, making China Israel’s third-largest trading partner, behind the U.S. and the UK (Observatory of Economic Complexity, accessed July 12). More than a thousand Israeli companies operate out of China, looking to take advantage of China’s technology manufacturing capacity.[2] Chinese companies have invested heavily in Israel’s transportation sector, although some of these projects (such as a high speed railway from Eilat to Ashdod) were put on hold (Globes, April 29, 2015). Notable successes include the Carmel Tunnels (People’s Daily Online, October 25, 2010), agreements to develop the ports of Ashdod and Haifa (Xinhua, July 11, 2019; Globes, June 24, 2020), and a light rail system in Tel Aviv (The Paper, June 7). Although Israel is not an official partner nation of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (IIGF Green BRI Center, accessed July 12), it became a member of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank in 2015, and Chinese investors have flocked to invest in technology start-ups in Israel’s ”Silicon Wadi” (TechNode, October 26, 2018).

While China is clearly a key part of the Israeli economy, however, Israel is not a major trading partner from Beijing’s perspective. Even if Sino-Israeli trade were to double, it would not place Israel among China’s top ten trading partners. However, Beijing derives other important benefits from its relationship with Jerusalem. First, trade relations form an important part of China’s foreign policy as leverage to achieve political goals. This was fully on display when, in 2013, the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu caved to Chinese demands to drop a lawsuit against the Bank of China for secretly bankrolling Hamas terrorist activities, which would have damaged the bank’s international reputation (Jerusalem Post, June 22, 2013). Israel reaps significant dividends from an economic policy that China uses to deliver international prestige and political leverage.

Military Technology and Commercial R&D

China has also historically benefitted from military technology transfers with Israel. In 2010, Israel was second only to Russia as a provider of weapons systems to China and a source for advanced military technology.[3] Israel has consistently provided China with military technology, both cutting-edge American weapons received from its “special relationship” with the U.S. as well as technology that Israel develops itself (CFR.org, July 30, 2019). This fact has consistently ruffled feathers in Washington: in 2000, the U.S pressured Israel not to sell PHALCON systems to China and ended up paying China $350 million dollars in compensation (Haaretz, May 13, 2002). In 2005, a brief crisis in U.S.-Israeli relations ensued after Washington sanctioned Tel Aviv for selling Harpy Killer drones to China. (Haaretz, July 27, 2005). More recently the roles have been reversed, with the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) benefiting from Chinese drone technology. The U.S recently blacklisted Chinese drone manufacturer SD DJI Technology Co. and grounded all 800 of the drones it had previously purchased from them, citing security concerns. But the IDF, which extensively uses DJI drones, has been more reluctant to remove or replace them (CTech, December 21, 2020). Despite occasionally canceling deals that draw the attention of the United States, the overall drive to share and sell military technology has remained consistent, although not always with the direct approval of the Israeli government (Haaretz, March 30).

Israel has also been an important source for technology transfers to China (Haaretz, June 4, 2015). These take place primarily through international business conferences, R&D connections, and joint business investments. For example, the Israeli Innovation Authority recently issued a seventh call for proposals under the “China-Israel Cooperation Program for Industrial Research & Development,” a research funding framework that is jointly implemented with the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (Innovationisrael.org.il, accessed July 12). China and Israel have also hosted many official events facilitating cooperation between Chinese and Israeli businesses (Jerusalem Post, December 8, 2020). Such ties encompass a variety of industries, from agriculture, to telecommunications, to chemicals and light manufacturing.

Agriculture in particular has been a major target for investment, as both sides view food security as being critical to national security: between 2007 and 2017, China invested over $5 billion in Israeli agriculture technology projects. Major acquisitions include China National Chemical Company’s takeover of Adama, a major player in the crop protection industry, and China Bright Food Group’s incorporation of Israel’s Tnuva Food Industries.[4] In China, joint projects like the Sino-Israeli Agricultural Town in Hebei, the Sino-Israeli Agri-tech Ecological City in Shandong, the Sino-Israel Agriculture High-tech Demonstration Park in Henan, and the Yunnan Sino-Israel Highland Agriculture Demonstration Park rely heavily on imported Israeli technology. (Hortidaily.com, August 31, 2020; EACi.co, September 17, 2017; Xinhua, August 8, 2018; Jerusalem Post, August 9, 2019). These projects are funded and supported by local and national government agencies in both countries, and tend to emphasize high-level agricultural technology, which can then be replicated and integrated into future Chinese enterprises.

Internet technology is also a major target for investment. Chinese firms such as Huawei and Alibaba have set up R&D centers in Israel, where they can benefit from the experience of Israeli firms and employees, which Chinese firms then learn from and integrate (GlobalTimes.cn, October 25, 2018). The close ties have persisted despite shifting geopolitical winds. In 2018, semiconductor exports from Israel to China jumped 80 percent to $2.6 billion, as Israel moved to fill a void left after U.S pressure effectively blocked several leading manufacturers from selling advanced chips to Chinese companies (GlobalTimes.cn, April 25, 2019). China’s investments in Israeli technology are extremely diverse and largely dominated by state-owned enterprises, acting in tandem with local, regional, and national government agencies.[5]

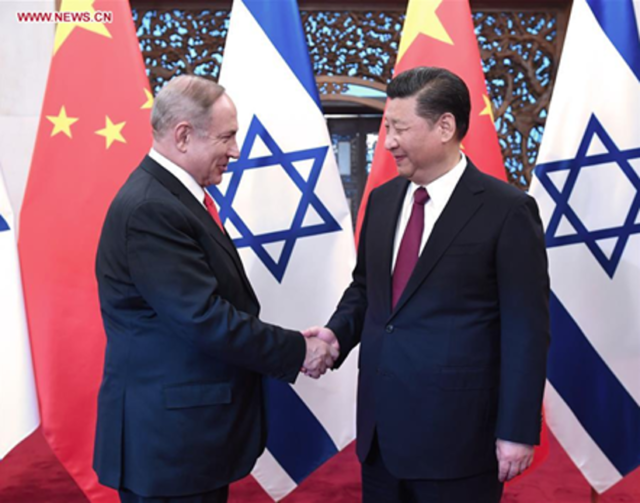

Both governments have promoted the notion of Israel as China’s “R&D Lab.” During a visit to China in 2013, Netanyahu gave a speech to Chinese and Israeli business leaders in Shanghai on the same day as the unveiling of the 2013 edition of China’s Israel-Palestine peace plan, in which he stressed:

“Israel is not as big as China. We have 8 million residents, approximately one-third of the population of Shanghai. But we manufacture more intellectual property than any other country in the world in relation to its size…If we create a partnership between Israel’s inventive capability and China’s manufacturing capability, we will have a winning combination” (Israel MFA, May 7, 2013).

Conclusion

Chinese support for the Palestinians and its recent anti-Zionist rhetoric should be primarily understood as a tool of foreign policy, which remains largely separate from continuing warm bilateral relations with Israel. In the most recent cases, China saw an opportunity to portray itself as a defender of international human rights and also score diplomatic points by criticizing the U.S. for its stance on the Gaza crisis, likely seeking to counter growing accusations of human rights abuses against Chinese Muslims in Xinjiang by the U.S. and its allies. Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying made that link explicitly when criticizing the United States for blocking a UNSC resolution critical of Israel. Calling American policy hypocritical for holding a “meaningless meeting on Xinjiang” while also blocking China’s resolution on Israel, she opined, “the U.S. should understand that the lives of the Palestinian Muslims are just as precious” (Chinese MFA, April 1).

The extensive network of commercial relations that now exists provides substantial economic and military/technological benefits to both sides. It is unlikely that either Israel or China would give up these benefits even under diplomatic pressure. Both governments occasionally make moves to appease the forces that take issue with their partnership: Israel will occasionally cancel deals with China under U.S pressure, and China will occasionally offer rhetorical and diplomatic support to the Palestinians without placing any meaningful pressure on Israel. But both sides also seem willing to tolerate such actions from the other without moving to substantially alter the relationship. Finally, it must be recognized that due to the entwined nature of the Chinese and Israeli economy, China is fundamentally unable to act as an impartial negotiator in the event of an Arab-Israeli peace process.

Dr. William Figueroa is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Middle East Center at University of Pennsylvania, where he recently also received his PhD in History. Dr. Figueroa’s work primarily focuses on historical Sino-Iranian relations in the late 19th-early 20th century. His commentary on modern Sino-Iranian and Sino-Middle East relations has appeared in outlets like Jadaliyya, The Diplomat, and BBC Persian.

Notes

[1] For more on this, see Gangzheng She; “The Cold War and Chinese Policy toward the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1963–1975.” Journal of Cold War Studies 2020

[2] See: Shira Efron, Karen Schwindt, Emily Hasle, “Chinese Investment in Israeli Technology and Infrastructure: Security Implications for Israel and the United States,” RAND Corporation, 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3176.html.

[3] See: Islam Ayyadi & Mohammed Kamal, “China-Israel Arms Trade and Co-Operation: History and Policy Implications”, Asian Affairs, 47:2 (2016), 260-273.

[4] See: Shira Efron, Howard J. Shatz, Arthur Chan, Emily Haskel, Lyle J. Morris, Andrew Scobell, “The Evolving Israel-China Relationship,” RAND Corporation, 2019, xiv,26 https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2600/RR2641/RAND_RR2641.pdf.

[5] See: Doron Ella, “Chinese Investments in Israel: Developments and a Look to the Future”, The Institute for National Security Studies, Tel Aviv University, 2021 https://www.inss.org.il/publication/chinese-investments/.