Refugees Flee into Yunnan After Renewed Violence Along Myanmar Border

Refugees Flee into Yunnan After Renewed Violence Along Myanmar Border

Violence along China’s border with Myanmar is threatening yet again to spill across into Yunnan Province. According to the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, more than 20,000 refugees have fled into Yunnan after renewed fighting between the Kachin Independence Army and Myanmar’s Armed Forces (Tatmadaw). These refugees are the second wave after more than 3,000 fled into China in late November 2016. In response, the prefectural government has begun setting up temporary shelters (Guanchazhe, November 22, 2016). It is unclear how it will cope with the much larger, second wave.

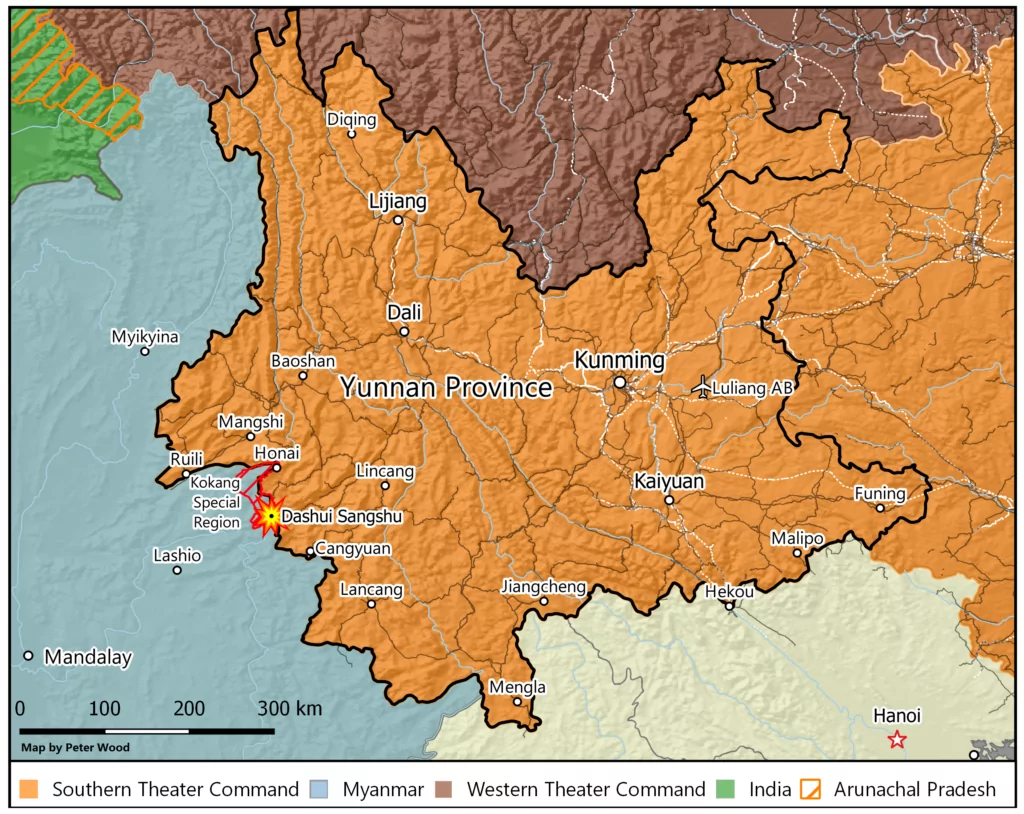

Three prefectures border the contentious area in Myanmar: Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture, Baoshan and Lincang. Together they have a population of almost six million people. A string of Border Guard Regiments sit at strategic points along Yunnan’s long borders with Vietnam and Myanmar. Two guard the area nearest to the Kokang Special Region, one to the north at Mangshi (芒市 formerly Luxi), and another to the south at Cangyuan (沧源). A PLA infantry brigade is also positioned nearby in Lincang to handle contingencies. Local police border guards (公安边防) have also been mobilized to help direct the stream of refugees.

The Kachin people are concentrated in northeast Myanmar. Further south, a separate group in the Kokang Special Region was the target of a 2015 Tatmadaw offensive that spilled over into Yunnan. Tensions have lasted for decades, but the most recent round dates to 2009 and has flared periodically since then. The continued violence has prompted PLA maneuvers and further complicated China’s relationship with the new democratic government of Myanmar. Perhaps more importantly, it also casts light on how China responds to crises on its borders.

While the PLA regularly holds joint training exercises, they are usually held near special training bases—not near the border. The previous set of exercises this large were held in 2015, after the Tatmadaw dropped ordinance in Dashui Sangshu (大水桑树), killing several Chinese farmers. In response, the PLA mobilized, and infantry, air defense, and fighter units were rotated close to the border in Lincang (China Brief, July 17, 2015). That set of exercises was the largest in the area in 30 years (Global Times, June 11, 2016).

In addition to mobilizing its armed forces and police units, Chinese diplomats have tried to place pressure on the Myanmar government to end the violence (MFA, March 9). China and Myanmar’s bilateral trade is worth $15 billion, making it Myanmar’s most valuable trade relationship (MFA, December 2016). Even so, previous diplomatic efforts apparently have had little effect, and the democratically elected government (led by President Htin Kyaw, but with Aung San Suu Kyi de facto in charge) maintains a delicate balance with elements of the former powerful military junta it replaced. It is unlikely that additional pressure from Beijing will keep the Tatmadaw and separatist movements from violence near the border.

Refugees crises, are likely to continue to be an issue on China’s border. But China lacks concrete policies to deal with the issue as a long-term problem. Syria’s refugee crisis has already prompted a debate among Chinese netizens regarding China’s refugee policies. Phoenix Media, responding to criticism that China has not taken in significant numbers of refugees, highlighted large numbers of mostly ethnic-Chinese accepted in the 1970s (Fenghuang, September 6, 2016). Indeed, anti-Chinese policies in North Vietnam in the 1950s and again after the fall of South Vietnam in 1975 prompted many ethnic Chinese to flee to China. China’s short border war with Vietnam in 1979 prompted an additional 260,000 to flee the Southeast Asian country (UNHCR, May 10, 2007).

China’s densely populated northeast is also under threat from a separate refugee crisis. In the mid-1990s, catastrophic famine and a general breakdown in the economy of North Korea killed hundreds of thousands and prompted a large number to cross into China in search of food. Even today, poor living conditions prompt many North Koreans to defect via the border with China. North Korean soldiers are also known to rob and murder Chinese citizens just across the border (China Brief, January 9, 2015). With tensions rising on the Korean peninsula due to Pyongyang’s active nuclear missile programs, the outbreak of war, or poor harvests could result in large numbers of Korean migrants fleeing to northeast China.

China, however, does not accept many people seeking to resettle. Between 2004–2013 China issued only 7,356 Foreigner’s Permanent Residence Cards (in contrast the U.S. issued 10 million during the same period) (Sixth Tone, October 12, 2016). Refugees have even more uncertain status. Although China is a signatory to the 1951 and 1967 international statutes that govern the treatment of refugees, domestically its law is handled via its entry and exit law (出境入境管理法) and 2005 national foreign affairs emergency law (国家涉外突发事件应急预案) (Fenghuang, September 6, 2016). Neither law has sufficient scope to adequately handle refugees under current conditions, much less the widespread emergency a crisis on the Korean peninsula would result in.

Peter Wood is the Editor of China Brief. You can follow him on Twitter @PeterWood_PDW

Notes

- Serial Marking – 50755. The three aircraft featured in CCTV footage are flying with three drop tanks and two air-to-ground rocket pods. The extra fuel is likely necessary because the border region is roughly 500km away, right at the edge of the J-10s 550km combat radius.