Russia Lures Georgia’s Secessionist Regions by Dual Citizenship

Russia Lures Georgia’s Secessionist Regions by Dual Citizenship

On October 13, at the 54th round of the Geneva International Discussions (GID) on the Russian-Georgian conflict, the Georgian delegation raised the issue of Russia granting dual citizenship to residents of Georgia’s breakaway regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The Georgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs considers this step an attempt by Moscow to eventually annex these breakaway territories outright. Additionally, the Russian, Abkhazian and South Ossetian participants walked away from the negotiation table to avoid talks with the Georgian side on the return of internally displaced persons (IDP) and refugees (Osce.org, October 13; Mfa.gov.ge, October 17).

Last month’s signing of an official agreement on dual citizenship between Russia and South Ossetia (Civil.ge, September 20) was a logical continuation of the events and trends that have taken place for the past decade. The present agreement, previously approved by Russian President Vladimir Putin (TASS, August 4), is based on the provisions of the Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance Between South Ossetia and the Russian Federation, concluded on September 17, 2008, and the Treaty of Alliance and Integration Between the Republic of South Ossetia and the Russian Federation, signed on March 18, 2015. Both documents contain a provision on the “fair and human settlement of issues related to dual citizenship.”

The signatories of the September dual citizenship agreement between Moscow and Tskhinvali notably had unequal official statuses. South Ossetia was represented by “Foreign Minister” Dmitry Medoev; whereas Russia was represented by its “ambassador to South Ossetia,” Marat Kulakhmetov, a former commander of a Russian peacekeeping unit in South Ossetia during 2004–2008, including the days leading up to when the August 2008 Georgian-Russian war was unleashed.

The accord—which allows the citizens of each entity (South Ossetia and Abkhazia have not been recognized as independent states except by Russia and a small handful of other countries) to obtain citizenship in the other without renouncing their original nationality—is valid for five years and will be automatically renewed for subsequent five-year periods unless one of the parties decides to terminate it. However, termination of the agreement does not automatically entail the termination of a person’s citizenship in either entity. Dual citizenship will allow the residents of South Ossetia living for years in economic hardship to enjoy additional rights to social security, pensions, and medical care from the Russian government. They will receive Russian citizenship under a simplified procedure. The agreement, while signed, has yet to be ratified by the parliaments of Russia and South Ossetia (Ekho Kavkaza, February 11, 2019; Cominf.org, September 20, 2021).

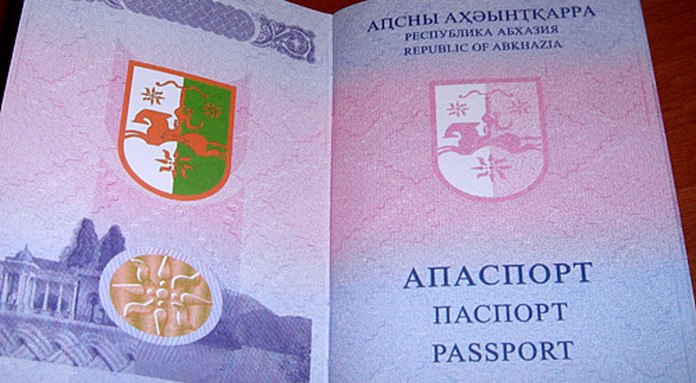

After the Russian Federation adopted a new law on citizenship in 2002, Moscow began a mass distribution of Russian passports to residents of breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In 2002, the percentage of Abkhazians with Russian passports was about 30 percent (Kommersant.ru, April 15, 2019). After Russia and South Ossetia signed their dual citizenship accord, the current “president” of Abkhazia, Aslan Bzhania, stated that his “republic” and Russia would sign an agreement on dual citizenship in the near future and that Abkhazian residents would receive Russian citizenship without red-tape barriers (TASS, Regnum, Realnoevremya.ru, September 21). Currently, 140,000 residents—57.4 percent of Abkhazia’s population—have this status. Crucially, the agreement with Russia would not imply granting Russian citizens Abkhazian citizenship, because of Sukhumi’s prohibition on the selling of Abkhazian real estate and some strategic units to foreigners. It is also worth noting, however, that Abkhazia’s “President” Bzhania as well as other top leaders already hold Russian passports. More than 11,000 citizens of Abkhazia voted at polling stations on the territory of Abkhazia during the latest elections to the Russian State Duma.

Political elites in South Ossetia and Abkhazia have different approaches to the dual citizenship question. In South Ossetia, the citizenship process might become an additional impetus for those advocating for the reunification of South Ossetia with Russia’s North Ossetia, many of whom have been calling for a referendum on the issue since 2012. In 2020, Moscow-backed Tskhinvali leader Anatoly Bibilov proclaimed in his state-of-the-nation address that reunification with the Russian Federation was a strategic goal for South Ossetia (Civil.ge, March 26, 2020; RFE/RL, January 8, 2014). Abkhazia, with its greater sensitivity to the territory’s self-declared “sovereignty,” seems to aim to extract maximum benefits from dual citizenship for its citizens who are experiencing severe social-economic problems.

Russia plans to increase financial injections to both Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2022 and 2023. The bulk of these sums will go toward social benefits and medical care (TASS, September 21). Meanwhile, dual citizenship will give residents of both secessionist regions further economic value and access to Russian government assistance. Moscow presumably hopes this will induce those populations to support the idea of joining Russia.

Granting dual citizenship to residents of Georgia’s secessionist regions is a reenactment of Russia’s tried-and-true recipes used in other post-Soviet states where Moscow masterminded various ethno-regional conflicts. The formal agreements on dual citizenship between Russia and Georgia’s two secessionist regions provide Russia with more leverage to achieve deeper and quicker incorporation of these territories and to further alienate them from Georgia. At the 54th round of the GID, Russia suggested launching the demarcation and delimitation of the “borders” of Abkhazia and South Ossetia with the rest of Georgia, having expressed “full support” to the endeavors of Sukhumi and Tskhinvali in this direction.

The decision to grant dual citizenship to the residents of breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia, thus, vividly demonstrates the unwillingness of Moscow’s leadership to make any positive progress in Georgian-Russian relations, which Tbilisi considers crucial for normalizing bilateral relations. Moreover, Moscow’s dual citizenship agreements with Sokhumi and Tskhinvali further reduce international opportunities for finding any mutually acceptable solutions to these conflicts.