Settling Scores – The Death of USS Cole Attack Accomplice Jamal al-Badawi

Settling Scores – The Death of USS Cole Attack Accomplice Jamal al-Badawi

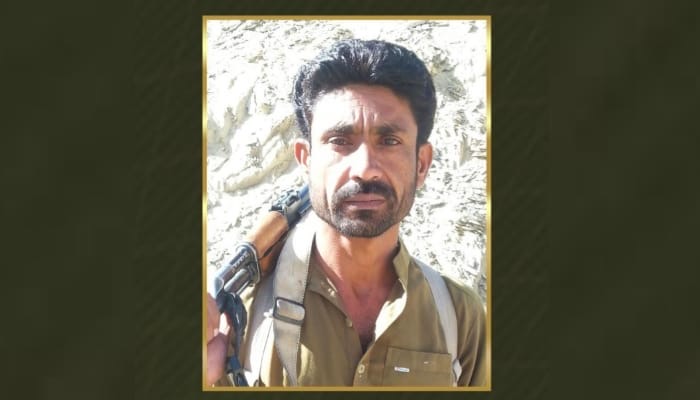

Long-time al-Qaeda operative Jamal al-Badawi was killed in what U.S. military officials called a “precision airstrike” on January 1 in the Yemeni governorate of Marib (al-Jazeera, January 6). Al-Badawi was a key accomplice in the October 2000 al-Qaeda led attack on the USS Cole in the Yemeni port of Aden. On January 6, al-Qaeda-linked jihadists released brief eulogies that seemingly confirmed al-Badawi’s death from a drone strike in Marib city, which is under the control of Saudi Arabia and its proxy forces (Asharq al-Awsat, January 5). [1]

Al-Badawi’s death—which the U.S. military has also confirmed—will have little or no impact on al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s (AQAP) ability to operate in Yemen. Al-Badawi was a legacy member of AQAP who had long since passed on whatever skills he may have had to new generations of operatives. Al-Badawi’s death by a purported drone strike will be more useful to AQAP for recruitment purposes than any services he might have been able to provide the organization.

The Afghanistan Connection

Little is known about Jamal al-Badawi’s early life beyond the fact that he was born sometime in 1960 or 1963 in al-Bayda, one of Yemen’s most restive and strategic governorates. Al-Bayda is on the border between the formerly independent countries of north Yemen (Yemen Arab Republic) and south Yemen (the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen). Due to its mountainous topography and proximity to the south, al-Bayda was used as a staging area for north Yemen’s covert operations against its enemies in south Yemen. The president of the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR), Ali Abdullah Saleh, and his cousin, General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar (currently the vice president of Yemen), saw the returning veterans of the wars in Afghanistan as useful proxies in their low-intensity war against their political enemies in the south.

President Saleh tasked General Mushin and the Yemeni security service, the Political Security Bureau (PSB), with recruiting and running first- and second-generation veterans of the wars in Afghanistan. The veterans played a key role in the 1994 war between north and south Yemen. The veterans that formed irregular units were some of the most effective and brutal fighters and led the assault and subsequent looting of Aden, the former of capital of south Yemen.

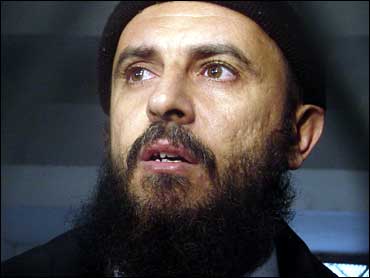

While it is not clear what, if any, role al-Badawi played in the 1994 civil war, it is certain that he spent time in Afghanistan in the 1990s, with his last trip thought to be in 1997-98. There, he met associates of Osama bin Laden, including bin Laden’s bodyguard, Walid bin Attash, who is imprisoned at Guantanamo Bay (al-Jazeera, September 10, 2017). Bin Attash was identified as having played a key role in the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salam and in the attack on the USS Cole.

Attacking the USS Cole

The October 12, 2000 attack on the USS Cole was a crude but well-planned operation that killed 17 U.S. servicemen and injured 39 more. The USS Cole entered the harbor at Aden for a routine refueling stop. The attack on the USS Cole was preceded by a failed attack on the USS The Sullivans, which had also stopped at Aden for refueling. This attack on The Sullivans failed because the suicide boat was so heavily laden with explosives that it sank before it could reach the ship. Al-Qaeda learned from this failure and employed the same strategy in its subsequent attack on the USS Cole. The boat, which al-Badawi helped acquire, was loaded with C4 explosives and driven into the side of the USS Cole by two suicide bombers who were both killed in the attack.

Al-Badawi’s role in the attack on the USS Cole came to light during the FBI-led investigation of the attack. Initially, Yemeni officials cooperated with FBI investigators, but their already minimal cooperation declined further as FBI investigators zeroed in on suspects—including al-Badawi, who was detained by Yemeni officials following the attack. Yemeni officials limited FBI access to al-Badawi and Fahad al-Quso in the months after the attack, saying both men had sworn on the Koran that they had nothing to do with the bombing. However, the lead FBI investigator, Ali Soufan, through a series of non-violent interrogations, pointed out the inconsistencies in al-Badawi’s testimony that eventually led al-Badawi to confess that he had indeed planned much of the attack (Newsweek, October 27, 2007).

Al-Badawi’s role in the attack was also cited by Walid bin Attash, who was captured in Karachi in April 2003. Attash, who was subjected to harsh interrogation measures at various black site prisons, provided testimony stating that al-Badawi helped secure the boat used in the attack and also traveled to the Yemeni town of Sa’dah—where there was a major arms market—to purchase the explosives used in the attack.

In April 2003, Al-Badawi escaped along with ten other suspects from the military prison where he was held ( al-Jazeera, January 6, 2019). After his recapture in 2004, al-Badawi, who had been sentenced to death by a Yemeni court, had this sentence commuted to a 15-year prison term (al-Jazeera, September 29, 2004). Al-Badawi had been indicted on 50 counts in absentia in a New York court in 2003.

Terrorist and Asset?

In February 2006, al-Badawi and 22 other prisoners, including Nasir al-Wuhayshi (who would become the emir of AQAP) and Qasim al-Raymi (the current emir of AQAP), escaped a Yemeni jail run by the Political Security Bureau (PSB) in Sana’a. The prisoners purportedly managed to dig a 460-foot tunnel unbeknownst to their jailers (al-Jazeera, February 6, 2006). The tunnel led them directly and conveniently to a mosque that was adjacent to the prison.

Yemen has been the site of frequent prison breaks, most of which have occurred at prisons run by the country’s security services. The 2006 prison break, in which al-Badawi escaped, was the most significant because a number of the prisoners who were not recaptured went on to play significant roles in AQAP. In 2007, al-Badawi turned himself into Yemeni authorities following protracted negotiations with the Yemeni government (Asharq al-Awsat, October 17, 2007). After he turned himself into authorities, al-Badawi was freed and allowed to return to his home near Aden after he pledged loyalty to then Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh. Yemeni authorities refused multiple requests to extradite al-Badawi before and after he was released.

Jamal al-Badawi’s escapes from prison, his commuted death sentence, and what was finally a de-facto pardon by the country’s president—despite ample evidence of his role in the bombing of the Cole—all point to his having a close relationship with elements of the Yemeni security services. Former Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh and the current vice president, General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar (who many Yemenis refer to as Baba al-Qaeda [the father of al-Qaeda]), both saw the usefulness of those men who had trained and fought in Afghanistan. These men, like all good proxies, were deniable and expendable. Yet, in the case of al-Badawi, it seems that he continued to enjoy some degree of protection by the state despite what must have been immense pressure from the U.S. to either imprison or extradite him.

Quiescence

Whatever the nature of the deal made with the Yemeni government, al-Badawi was protected from arrest and extradition until his assassination by a U.S. drone. Following his de-facto pardon in 2007, little is known about what role, if any, al-Badawi played in AQAP. It is likely that he maintained contact with both AQAP operatives and members of the Yemeni security services, who would have monitored his whereabouts.

There is little doubt that al-Badawi was nothing more than a legacy member of al-Qaeda who had little, if anything, to do with AQAP’s current operations in Yemen. His death will have no impact on the ability of AQAP to operate in Yemen, but AQAP will—as it always does—capitalize on the death to recruit new low-level operatives and foot soldiers.

Jamal al-Badawi’s career points to the complex and shadowy nature of the relationship between Yemeni security services and jihadists. Had al-Badawi been captured alive and questioned by a skilled interrogator like Ali Soufan, his testimony would have undoubtedly contributed greatly to the United States’ understanding of how jihadist groups like AQAP may interact with some elements of the state. This information would be of particular interest now, since a disintegrating Yemen is rife with such interactions ( Al-Bawaba, August 26, 2018). Jihadists, including members of AQAP, are active along almost all of Yemen’s frontlines as various factions backed by Saudi Arabia and the UAE battle Yemen’s Houthi rebels (al-Jazeera, November 28, 2018).

Notes

[1]See: https://ent.siteintelgroup.com/index.php?option=com_acymailing&ctrl=archive&task=view&mailid=12993&key=X3D3CLmy&subid=1472-t9ir9gm3ghmVr7&tmpl=component [2] See: https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/csrt_transcript_al_nashiri_released_6.13.16_highlighted_for_csrt_upload.pdf [3] See: https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/01/21/playing-a-double-game-in-the-fight-against-aqap-yemen-saleh-al-qaeda/