The New PLA Joint Headquarters and Internal Assessments of PLA Capabilities

The New PLA Joint Headquarters and Internal Assessments of PLA Capabilities

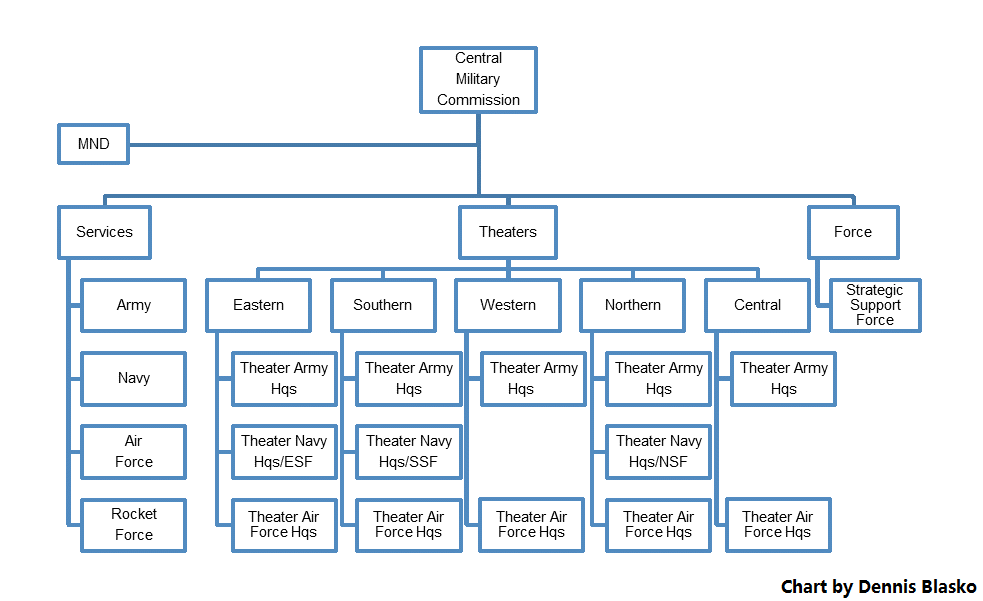

The creation of new multi-service (joint) headquarters organizations at the national (strategic) and theater (operational) levels is a major component of the current tranche of reforms underway in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). These changes further concentrate ultimate leadership of the armed forces in the Central Military Commission (CMC), led by Communist Party General Secretary and President of the People’s Republic of China Xi Jinping, supported by an expanded joint organizational structure replacing the former four General Departments. Directly beneath the CMC, five new joint Theater Command headquarters have superseded the seven former Military Region headquarters.

These new headquarters contribute to the reforms’ goals to resolve problems in military readiness and weaknesses in combat capabilities, build an integrated joint operations system, and increase the PLA’s ability to, according to Xi’s guidance, “fight and win” informationized war. Under the new structure Theater Commands are responsible for planning joint operations for a specific strategic direction and executing large-scale joint training. The four service headquarters, the newly formed Army headquarters along with the Navy, Air Force, and upgraded Rocket Force headquarters, are responsible for “construction” or “force building,” which includes organizing, equipping, and training operational units to prepare them to participate in operational deployments and large joint exercises. These changes seek to reduce levels of command, shrink the overall number of headquarters personnel, and streamline decision-making, planning, execution, and evaluation throughout the PLA (Xinhua, January 1).

The adjustments to the PLA’s headquarters structure are to be accomplished by 2020, the date announced a decade ago as the second milestone in the “Three-Step Development Strategy” to modernize China’s national defense and armed forces (Defense White Papers, 2006 and 2008). This date is underscored in the recently announced “five-year military development plan,” which has the goal of completing the mechanization and making “important progress” on “incorporating information and computer technology” in the PLA by 2020—exactly the same goal as the milestone announced by the 2008 White Paper (China Military Online, May 13). The five-year implementation period implicitly acknowledges that many details remain unsettled and must be refined to eliminate overlaps or gaps in responsibilities. Additional reforms are expected in coming decades as the PLA continues its “Three-Step Development Strategy” with the final completion date of mid-century, 2049, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic.

These reforms come as the Chinese military has reached a critical point in its long-term modernization process. The PLA has recognized that many traditional strategic and operational concepts and practices must be revised as potential threats and economic imperatives have changed. Fundamental to this new thinking are the official statements that “China is a major maritime as well as land country” and “The traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned.” Therefore, “great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests. It is necessary for China to develop a modern maritime military force structure commensurate with its national security and development interests…” (Defense White Papers, 2013 and 2015). Both statements are related to the goal of breaking the “big Army” concept (“大陆军”观念 or 思维) (China Military Online, February 3).

Though these new requirements have been verbalized officially only in recent years, the trends in PLA force development toward greater emphasis on missile, naval, air, and cyber/electronic warfare capabilities have been apparent for the past two decades. Employing these “new-type combat forces” in new missions demands integrated command and control of units operating at much greater distances from China’s borders than ever before. Though ground forces have not been left behind totally in the current phase of modernization, this shift in doctrine comes at the expense of the PLA’s traditional base of power and leadership, the Army and Army generals.

The following sections describe the efforts in motion to satisfy the PLA’s increased need to develop joint headquarters and officers capable of commanding joint forces. As with other aspects of modernization, these efforts begin with the realistic acknowledgement of existing shortfalls in PLA capabilities.

Internal Assessments of PLA Capabilities

Critiques of inadequacies in joint training and command capabilities in all services are perennial topics found in the domestic Chinese military literature though often buried in long texts. For example, less than a year ago, the commander and political commissar of the former Nanjing Military Region commented that the low level of joint training and poor joint training mechanisms have restricted integrated operations and are fundamental issues in the transformation of the military (Xinhua, July 3, 2015). More recently, the English-language edition of China Military Online stated that there is a “shortage of officers who have a deep knowledge of joint combat operations and advanced equipment.” Moreover, the PLA has “developed and deployed many cutting-edge weapons, including some that are the best in the world, but there are not enough soldiers to use many of those advanced weapons. In some cases, soldiers lack knowledge and expertise to make the best use of their equipment” (China Military Online, April 28). Similar criticism is common in the Chinese-language military media.

Internal critiques like those above, along with the identification of other shortcomings in organization, doctrine, training realism, and logistics, are intended to inform PLA personnel of areas that need to be improved and motivate them to work harder to improve overall capabilities. These assessments frequently follow descriptions of positive developments and often are couched in terms of “some units” or “some commanders,” but are widespread enough to indicate that the problems are serious systemic shortcomings for much of the entire force.

Generally speaking, the PLA sees itself as not having the military capabilities and capacity to be confident in accomplishing many of the tasks it may be assigned. In 2006, then-CMC chairman Hu Jintao summarized the situation in a formula known as the “Two Incompatibles” (两个不相适应), which referred directly back to his own doctrinal vision known as the “historic missions” (China Brief, May 9, 2013). The “Two Incompatibles” said the PLA’s “level of modernization does not meet the requirements of winning local war under informatized conditions and its military capability does not meet the requirements of carrying out its historic missions at the new stage of the new century.” Though appearing frequently during Hu’s tenure as CMC chairman, the formula has been used less regularly since Xi replaced Hu, but as recently as mid-April 2016 (China Military Online, April 19).

Since 2013, under Xi’s leadership, the “Two Big Gaps” (两个差距很大) and the “Two Inabilities” (两个能力不够 – translations of the Chinese terms vary) have come to prominence as general descriptions of PLA capabilities. Similar to the “Two Incompatibles,” the “Two Big Gaps” states “(1) there are big gaps between the level of our military modernization compared to the requirements for national security and the (2) level of the world’s advanced militaries” (China Air Force, April 16, 2013).

The “Two Inabilities” reinforces these points and further identifies problems specifically in officer capabilities: The PLA’s ability “(1) to fight a modern war is not sufficient, (2) our cadres at all levels ability to command modern war is insufficient” (China Air Force, July 12, 2013). These two formulas sometimes are paired together and have been associated with the “Two Incompatibles” (China Military Online, February 5, 2015 and CPC News Network, December 11, 2013).

Beginning in 2015, the “Five Incapables” (五个不会) formula began to be used which criticizes “some” leaders’ command abilities: “Some cadre cannot (1) judge the situation, (2) understand the intention of the higher up authorities, (3) make operational decisions, (4) deploy troops, and (5) deal with unexpected situations” (China Military Online, February 5, 2015). This assessment is a particularly stark acknowledgement of operational and tactical leadership shortfalls. It is an example of why the PLA prioritizes officer training over troop training as reflected in another common slogan: “in training soldiers, first train generals (or officers)” (练兵先练将 or 练兵先练官) (China Military Online, January 13 and April 12).

Though the public acknowledgement of weakness may sound strange to foreign ears, in Chinese military thinking which is based on Marxist theory, these assessments represent the “thesis” of positive developments balanced by the “antithesis” of remaining problem areas, which are to be overcome through scientific efforts leading to a “synthesis” signifying progress. The process is then repeated, especially when new technologies and weapons are issued to the force.

The judgments described above are well known to the PLA senior leadership and frequently repeated in their own writings or speeches. The reforms underway are intended to address the shortcomings in joint command organization and officer development.

The New Joint Headquarters

The new CMC staff organization consists of 15 departments, commissions, and offices (China Military Online, January 11). These new staff offices expand a few previously existing CMC organizations, incorporate the functions and many of the personnel from the former four General Departments, and, in the case of the National Defense Mobilization Department, take over the responsibilities of the Military Regions in commanding the provincial Military Districts, PLA reserve units, border and coastal defense units, and the militia.

The CMC staff organization primarily supports the members of the CMC, presently composed of the supreme civilian party and government leader, Xi, and 10 senior PLA officers, 6 Army generals, 1 Navy admiral, 2 Air Force generals, and a Rocket Force general. As such, the CMC itself is a joint organization with its personnel distributed among the services very close to how the 2.3 million personnel in the PLA (prior to the 300,000 man reduction) were allocated: approximately 73 percent Army/Second Artillery, 10 percent Navy, and 17 percent Air Force. The composition CMC leadership is not set by law and is subject to change.

A photograph of the CMC and the “new heads of [its] reorganized organs” revealed 69 officers, including the 10 CMC generals/admiral and another 59 CMC staff directors/officers, of which 51 were Army/Rocket Force, five Navy, and three Air Force. [1] (Xinhua, January 11). Though the CMC is a joint organization, its leaders and its primary staff officers still are mostly Army officers. The percentage of non-Army officers in lower-level CMC staff billets is not known.

Continuing the dominance of Army officers, all the new commanders and political commissars of the five Theater Commands are from the Army. [2] Each Theater is assigned responsibility for a strategic direction (战略方向) and is to develop theater strategies, directional strategies, and operational plans for deterrence, warfighting, and military operations other than war (MOOTW). Theater headquarters may command units from all services in joint operations and MOOTW tasks and are responsible for organizing and assessing joint campaign training and developing new methods of operation (China Military Online, February 1 and March 3).

The Theater Commands are structured as joint headquarters with Army and non-Army deputy commanders and political commissars, a joint staff from all services, and service component commands. Each Theater has a subordinate Army headquarters and Air Force headquarters, while the Eastern, Southern, and Northern Theater Commands also have Navy components that retain the names East Sea Fleet, South Sea Fleet, and North Sea Fleet, respectively. These component headquarters are the key link to both the Theater Commands and national-level service headquarters. Service component headquarters have operational command of units in war and may serve as campaign headquarters (战役指挥部) under the Theater Commands. They also perform “construction” leadership and management functions under the supervision of the service headquarters in Beijing. Moreover, they may act as emergency response headquarters for MOOTW missions. [3]

Rocket Force staff officers are assigned to Theater Command headquarters, but Rocket Force units appear to remain under the direct command of the Rocket Force service headquarters in Beijing with conventional (non-nuclear) units available to support theater missions.

<See attached chart at the bottom of this page>

Training and Developing a Contingent of Joint Officers

Since their establishment, Theater Command headquarters have been engaged in functional training and evaluation to ensure their staff officers are qualified to perform their duties. For example, the Northern Theater conducted a month-long “joint operations duty personnel training camp” focused on conditions in the services and the Theater’s area of responsibility consisting of lectures, demonstrations, hands-on training, and assessments (China Youth Online, February 25).

Many Theater staff officers were selected from the best of the former Military Region officers. Within the Northern Theater headquarters staff officers were required to have spent at least two years in a headquarters at or above group army level plus have participated in or organized a large-scale joint exercise. Yet even with this background many officers express lack of confidence, known as “ability panic” (本领恐慌), in their new positions. Accordingly, the Theater has created a “Three-Year Program for Building Joint Operations Command Personnel” (《联合作战指挥人才建设3年规划》) (China Military Online, May 5). Such programs will be necessary not only for the first batch of Theater-level staff officers, but also for new staff officers assigned at that level in the future.

Over the past decade, the Military Regions and the services experimented with a number of programs to develop joint officer capabilities. In December 2014, the Ministry of National Defense spokesman provided this update:

After a trial period, the PLA is now applying the professional training scheme for joint operation commanding officers in the whole military. This scheme aims to optimize the command posts for joint operation commanding officers, conduct differentiated training for joint operation commanders and administrative officers, and for joint operation staff officers and other staff officers, and establish a new mechanism for the selection, training, evaluation and appointment of joint operation commanding officers, so as to improve the training of joint operation commanding officers (China Military Online, December 25, 2014).

These programs will be even more important with the establishment of the Theater Commands. Likewise, the PLA educational system of universities and academies will need to adapt its curricula and student composition to prepare officers for joint assignments and the PLA’s new maritime orientation.

Conclusions

The current leadership line-up of CMC members, CMC staff, and Theater headquarters is certain to change before 2020. A measure of the PLA’s commitment to jointness will be the percentage of non-Army senior officers assigned to these billets. One of the most substantial developments, both symbolically and operationally, would be the assignment of Navy or Air Force officers to command one or more Theaters, particularly the Eastern and Southern Theater Commands where the immediate need for integrated maritime and aerospace operations is greatest.

Over the long run, the PLA must develop an education, training, and assignment scheme to prepare officers of all services for joint command and staff duties. The best practices learned from experimentation from previous years will need to be codified and applied throughout the entire force. This process will affect many aspects of the personnel system as it has been implemented for the past 60 years.

Meanwhile, doctrine and strategy must continue to evolve to support the PLA’s expanded missions, technology, and potential areas of operation. The shift in mindset from a continental Army to an integrated joint force capable of operating both inside and beyond China’s borders and three seas will probably take at least a generation to achieve. Commanders and staffs at all levels must prove themselves qualified to perform these new tasks not only in academic settings but also in real world missions. They will raise their level of confidence in their own abilities through the actual performance of missions, not just talking or reading about them. A significant level of unease among operational and tactical commanders and staff is clearly evident in the official Chinese military literature.

The military’s senior leadership understands the many challenges confronting the PLA as it continues its multi-decade, multi-faceted modernization program. In the immediate future, the disruptions caused by changes underway could result in a more cautious attitude toward the employment of force by China’s military leadership, but not necessarily its political decision-makers.

Dennis J. Blasko, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army (Retired), is a former U.S. army attaché to Beijing and Hong Kong and author of The Chinese Army Today, second edition (Routledge, 2012).

Notes

1. The Rocket Force does not yet have a distinctive uniform different from the Army, so it is not possible to distinguish between Army and Rocket Force officers in the photo.

2. Each Theater commander has provided at least one interview to the Chinese media.

3. China Military Online, February 2, 2016 and May 10, 2016 https://www.81.cn/jmywyl/2016-02/01/content_6883951.htm and https://www.81.cn/jfjbmap/content/2016-05/10/content_144076.htm, spells out these missions for Theater Command Army headquarters. I assess the other services’ Theater Command headquarters have similar functions.