The PLA at 90: On the Road to Becoming a World-Class Military?

The PLA at 90: On the Road to Becoming a World-Class Military?

China recently celebrated the 90th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) with a parade and military exercises at the Zhurihe Training Base in Inner Mongolia (CCTV, July 30). Although the display was characterized as a demonstration of China’s growing military might—particularly new equipment and weapons platforms, including advanced missiles and aircraft—the event also provided important indications of the PLA’s approach to operations and the first-ever demonstration of an actual military operation during a parade. The PLA’s anniversary celebration thus reflected its progress toward becoming a “world-class military” and confidence despite remaining challenges related to the ongoing, historic reforms. Shortly after the parade, Xi Jinping announced: “The PLA has basically completed mechanization and is moving rapidly toward ‘strong’ informationized armed forces,” achieving the 2020 goal of its “three-step development strategy” (PLA Daily, August 2).

PLA Parades in Perspective

Traditionally, PLA parades such as those held in Beijing in 2009 and the 2015 Victory Day Parade—have tended to be highly choreographed displays that are counterproductive in terms of the force’s operational capabilities in actual combat (实战), taking considerable time away from training for the units involved (China Brief, September 24, 2009). For prior parades in Beijing, units from all over the country were required to send personnel and equipment to prepare for the drive down Chang’an Jie months in advance, losing the opportunity to train in a more realistic way for almost an entire training season.

The ongoing military reforms, announced in 2015 and set to continue until 2020, are intended to bridge the gap between the “two incompatibles,” the “two inabilities,” and “five incapables” relative to where the State and Party need the PLA to be (China Brief, May 9, 2013). In other words, the true test for the PLA is whether the units that operate its equipment can actually perform the missions assigned, and that depends on the level and realism of training the units receive and the quality of their personnel. That this parade was organized at a training base at least enabled some units to engage in training while preparing for the parade, reflecting a greater commitment to preparation for combat operations. Additionally, PLA parades have been opportunities to display a vast array of new equipment, which has greater potential capabilities than the older equipment replaced, signaling the military’s modernization.

Integrated Combat Operations

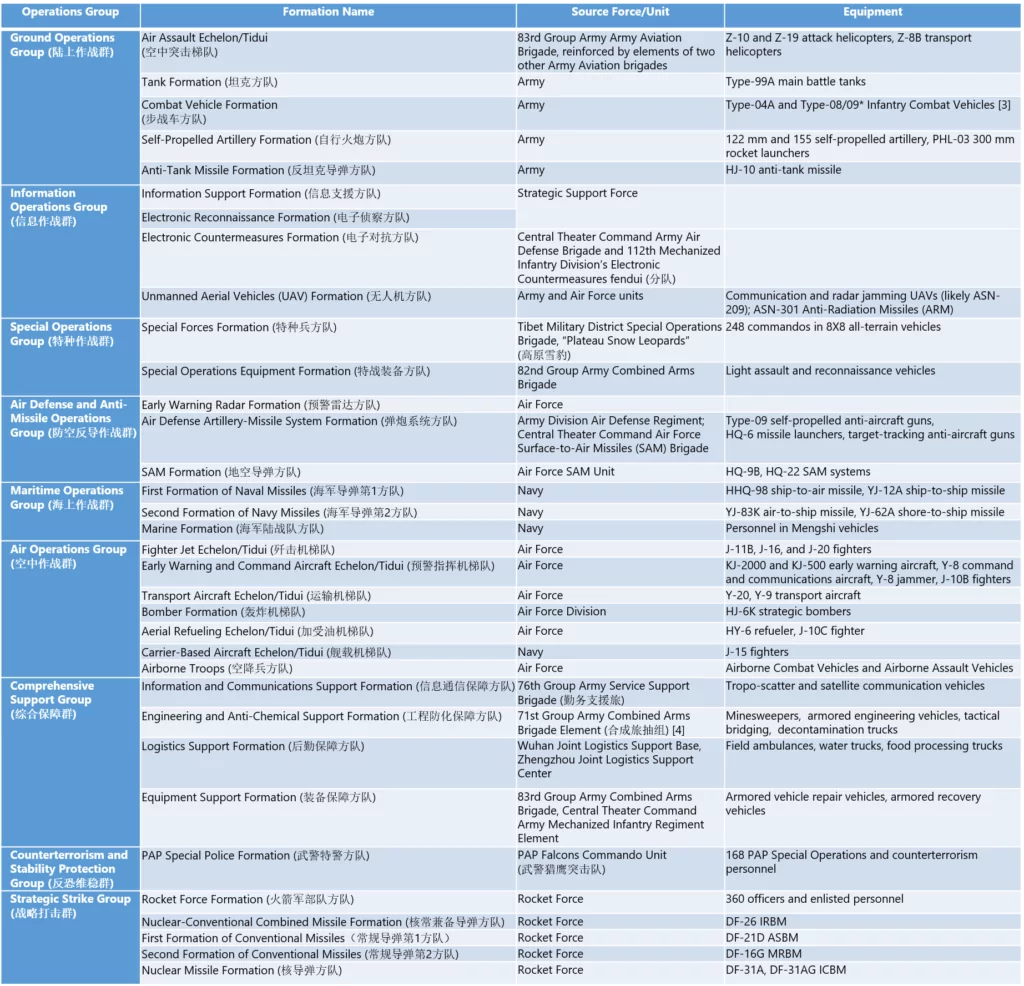

The parade itself was centered around the display of the PLA’s joint force units responsible for actual operations, known as “operations groups” (作战群) and other support groups (Xinhua, July 31, 2017). In modern combat, the PLA seeks to integrate the capabilities of these various groups in joint “systems of systems operations” (体系作战). Each group was composed of a series of “formations” (fangdui, 方队) or aerial formations/echelon (tidui, 梯队), which were comprised of units from one or more service or the People’s Armed Police (PAP). [1] Unfortunately, the parade did not provide new insights about the PLA’s evolving organizational structure, which is increasingly centered on combined arms brigades (hechenglu, 合成旅). Nonetheless, the formations associated with each operations group revealed the types of weapons and equipment that will be employed in future joint campaigns. [2]

In addition to the units that passed in review in the air or on the ground, Xi Jinping also reviewed seven large formations of roughly 900 dismounted personnel each. Across from the VIP reviewing stand, the Central Theater Army’s 112th Mechanized Infantry Division set up a static display of tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, and artillery, along with other weapons from the Rocket Force, like the CJ-10 cruise missile. After the ground and air formations had passed, these seven personnel formations ran at “double-time” to form up opposite the reviewing stand, where they listened to Xi’s speech on the requirements for PLA modernization.

In addition to the units that passed in review in the air or on the ground, Xi Jinping also reviewed seven large formations of roughly 900 dismounted personnel each. Across from the VIP reviewing stand, the Central Theater Army’s 112th Mechanized Infantry Division set up a static display of tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, and artillery, along with other weapons from the Rocket Force, like the CJ-10 cruise missile. After the ground and air formations had passed, these seven personnel formations ran at “double-time” to form up opposite the reviewing stand, where they listened to Xi’s speech on the requirements for PLA modernization.

A Historic First for Army Aviation

The parade also marked a historic moment for PLA Army Aviation: the first time the PLA has ever executed tactical procedures during a parade, marking the “public debut” of an Army airborne assault unit (China Daily, July 31). The demonstration was conducted by an air assault brigade (空中突击旅) from the 83rd Group Army, supported by elements of two other Army Aviation units (Xinhua, July 30). The air assault simulated the integration of reconnaissance, attack, and transport helicopters with infantry to deliver soldiers to a distant location on a battlefield. It is unclear if the infantry troops transported by the helicopters are assigned permanently to the army aviation brigade.

The air-assault demonstration brought together a series of army-aviation unit maneuvers meant to display the ability to assault and secure a remote landing zone (China Military Online, July 31). The demonstration involved an initial sortie by a “reconnaissance and alert unit,” which flew over the landing zone to determine the situation, followed by a “firepower assault unit” composed of attack helicopters that secure the landing zone by targeting and neutralizing nearby known enemy positions. Finally, three “air-landing units” delivered the infantry troops to the battlefield (here on evenly-spaced concrete pads), where they disembarked and would have proceeded to fight. These units were supported by an escort unit to provide extra firepower. Finally, the troops reassembled at their helicopters and stood by for the remainder of the parade. While not a realistic test of capabilities, this was a major step for a PLA parade—an improvement that added actual value compared to marching or flying straight lines simply for show—while reflecting the progress made by Army Aviation. [5]

The Information Operations Group on Display

Notably, the parade also showcased the information operations group, a joint-force wartime construct that would bring together the various, disparate elements responsible for cyber, electronic, and psychological warfare into an operational command at strategic, campaign, and tactical levels. Prior to reforms, the national-level or strategic information operations group would have drawn units from the General Staff Department (GSD), the General Political Department (GPD), and the General Armament Department (GAD). The newly-established Strategic Support Force (SSF) has knocked down the silos between these units, incorporating them into a cohesive force in peacetime both to facilitate the transition to wartime and to construct a war-fighting force capable of achieving dominance in these critical domains (China Brief, February 6, 2016; China Brief, December 21, 2016).

The information operations group formation itself resolves a few remaining questions on the relationship between the SSF and China’s wartime structure for information operations. First and foremost, the parade formally indicates the SSF’s role as the primary fighting force for information operations and “information support” (信息支援), which involves C4ISR support in critical, emerging domains like space, cyber, and the electromagnetic spectrum. Like the relationship between the other services and their corresponding operations groups—the PLA Navy with the maritime operations groups, the PLA Air Force with the air operations group, and the PLA Rocket Force with the strategic strike group—the SSF serves as the central component of the information operations group. Secondly, while the SSF is the primary fighting force for information operations, it is not the only one. The SSF only incorporates strategic-level and former GSD, GPD, and GAD units, not those from the theater or campaign-level, which are now part of the new Theater Commands (战区). For instance, the electronic countermeasures (ECM) formation came from the PLA Army, specifically from an air defense brigade and a division’s ECM fendui (电子对抗分队) (Xinhua, July 30). What is still unclear are the composition of information operations groups of different echelons, whether tactical or campaign-level groups could have a national mission, and how their respective missions would be coordinated or deconflicted.

China’s Strategic Deterrence on Parade

The strategic strike group showcased the newly-elevated PLA Rocket Force (PLARF), which is considered the “core force” for China’s strategic deterrence (Xinhua, July 30). The PLA’s 90th anniversary served as an occasion to display and unveil some of the PLA’s most advanced missiles. [6] The DF-26, an intermediate-range ballistic missile with a maximum range of 4,000 kilometers, was highlighted as having combined nuclear and conventional (核常兼备) capabilities (Xinhua, July 30). The DF-21D medium-range anti-ship ballistic missile, which has a range of 1,750–2,000 kilometers, would have particular utility against maritime targets and thus is popularly known as the “carrier-killer” missile (Xinhua, July 30). Of its conventional missiles, the PLA also displayed the modified DF-16, a medium-range ballistic missile with a range of 800–1,000 kilometers (Xinhua, July 30).

The parade concluded with the first parade appearance of the DF-31AG, a modified version of the road-mobile DF-31A intercontinental ballistic missile (Xinhua, July 30). The new version could have a range over 11,000 kilometers and greater survivability due to the use of a transporter erector launcher (TEL) that can go off-road, over rougher terrain to enhance its mobility (IHS, August 8). A week before the parade, a model of the DF-31AG was displayed at the PLA Military Museum in Beijing (South China Morning Post, July 24). These dual-capable, conventional, and nuclear missiles constitute integral elements of China’s deterrence capabilities that enable regional defense and long-range precision strike. [7]

Real Training Off the Parade Ground

Because the parade was held at Zhurihe in the middle of the large unit training season, several units took the opportunity to conduct training that is much more realistic than what occurred on the parade ground. Prior to the parade, elements of the 112th Mechanized Division and the same Army Aviation units that were seen in the parade conducted live fire field training, simulating an actual air assault coordinated with ground maneuvers (CCTV, August 1). Moreover, the parade was preceded by a combined ballistic and cruise missile exercise against mock targets that reportedly resembled U.S. THAAD missile batteries and models of U.S. F-22 stealth fighters (Fox News, August 2). This exercise was conducted by units from the Air Force and Rocket Force, which fired live HQ-6, HQ-16, and HQ-22 SAMs and DF-26, DF-16, and CJ-10 ballistic and cruise missiles, respectively (The Diplomat, August 3).

Conclusion

Although much of the media coverage to date has focused on the symbolic and political importance of the parade as a powerful reaffirmation of the military’s loyalty to the CCP and Chairman Xi Jinping ahead of the pivotal 19th Party Congress later this year, the parade reveals a force that is still growing and developing, concurrently envisioning itself as a modern, advanced military and acknowledging its own weaknesses. The parade demonstrated an important development in the PLA’s pursuit of developing improved joint operations capabilities by incorporating the key components necessary for combat operations, supported by information support, electronic warfare, logistics support, and other non-combat units. The air-assault demonstration, the integration of the SSF through the information operations group, and the prominent display of the PLA’s latest and most advanced missiles are clear signs of the PLA’s developing operational capabilities and evolving force structure. The demeanor of the both PLA leadership and troops indicated a highly disciplined force. The parade and media coverage both signify that the Party will always command the gun and should not be discounted as a powerful deterrent signal to foreign observers of the PLA’s progress and the scope of its ambition.

Dennis J. Blasko, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army (Retired), is a former U.S. army attaché to Beijing and Hong Kong and author of The Chinese Army Today (Routledge, 2012).

Elsa Kania is an analyst focused on the PLA’s strategic thinking on and advances in emerging technologies. Her professional experience has included working at the Department of Defense, the Long Term Strategy Group, FireEye, Inc., Harvard’s Belfer Center, and the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy. She is fluent in Mandarin Chinese.

Stephen Armitage is a former DOD analyst, US expat and researcher primarily focused on Chinese information operations and emerging tech.

Notes:

- The terms fangdui and tidui are used almost exclusively for parades and are not operationally significant.

- For a full listing of formations in the parade see: PLA Daily, August 1 and related official media coverage.

- The coverage of the parade refers to the Type-08 infantry fighting vehicle. However, previously that eight-wheeled vehicle was called the Type-09, ZBD09, or ZBL-09.

- The term 抽组 (chouzu) is typically used to refer to a group, element, or detachment selected from a larger unit.

- In the early 1990s, the PLA Army only had about 100 helicopters, none of which were attack helicopters. At present, the PLA Army has over 1,000 helicopters in at least 14 operational brigades in all group armies and the Xinjiang Military District, and is half the size of the PLA Army in the early 1990s (NetEase). For comparison, the U.S. Army, at 465,000 personnel, less than half the size of the PLA Army, has roughly 4,000 helicopters and has been conducting air assault operations in combat since the mid-1960s (DOD, May 31). See: The Military Balance 2017, International Institute for Strategic Studies, London, pp. 46, 48.

- Please note that all details on missile ranges are taken from the Department of Defense’s Report, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2017,” https://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2017_China_Military_Power_Report.PDF?ver=2017-06-06-141328-770.

- Note that although the DF-31 was included in the 1999 parade, it was not until 2006 that the U.S. Department of Defense declared it had achieved “initial threat availability.” (See: DoD Report to Congress 2007, p. I.) The status of the DF-31AG has not been confirmed at this point.