Recent ILD Activity Suggests Expanded Mandate

Recent ILD Activity Suggests Expanded Mandate

Executive Summary:

- The Party’s International Liaison Department (ILD) has started conducting outreach to U.S. student groups—especially those at policy schools at elite universities—signaling an expansion of its mandate.

- Past changes to the ILD’s mandate have been the result of insecurity, but current developments arose from internal perceptions of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) increasing national status in the 2010s.

- U.S. institutions that facilitate the ILD’s youth outreach are misreading the department’s intentions, as it now prioritizes promoting PRC global leadership over genuine political exchange.

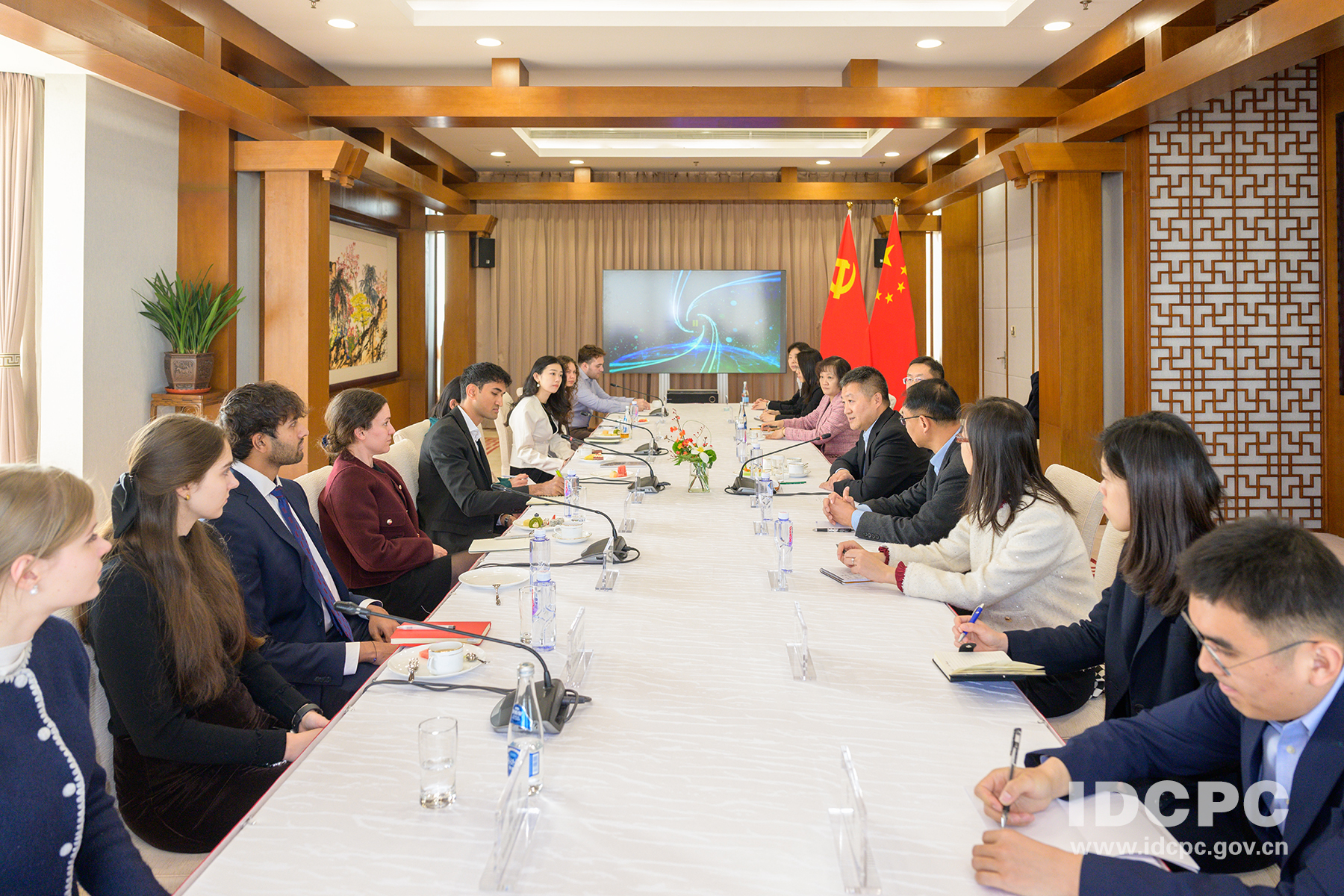

In early January, the China–U.S. Exchange Foundation (CUSEF; 太平洋国际交流基金会), a Beijing-based non-profit, organized a trip to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), bringing U.S. college students to Beijing, Guiyang, and Chengdu (CUSEF (Beijing), January 14). In Beijing, the students met with Lu Kang (陆慷), the vice minister of the International Liaison Department (ILD) of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) (中共中央对外联络部) (ILD, January 6). The meeting was celebrated as part of Xi Jinping’s “50,000 in 5 years” (五年五万) initiative, which follows his 2023 announcement that the PRC will encourage 50,000 young Americans to visit the country through exchange and study programs between 2023–2028 (Embassy of the PRC in the United States, December 7, 2024).

Visits to the ILD are rare. The department has hosted only six public meetings with U.S. students, all since 2024. In addition to the January meeting facilitated by CUSEF, meetings have included delegations from the University of Pennsylvania, Columbia University, Johns Hopkins University, and Harvard University (see Table 1).

The ILD’s participation in the “50,000 in 5 years” initiative reflects a growing mandate. Described as the “CCP’s ‘ministry of foreign affairs’” (中国共产党的“外交部”), its scope of work traditionally covered promoting party-to-party relations and sharing the CCP’s models of governance and development with receptive institutions, along with other auxiliary foreign policy functions (Hoover, 2019). These efforts have primarily been intended to expand the CCP’s “circle of friends” (朋友圈), but recent youth visits show a new method of outreach (The Paper, June 27, 2016). The ILD now employs a grassroots approach that bypasses political points of contact, suggesting a more assertive approach to international influence.

From ‘Demystification’ to Student Outreach

Student engagement with the ILD is the most recent component of the department’s “Enter the ILD” (走进中联部) program. The program was first introduced in 2007 with an ILD “Open Day” (开放日). Although held in the period’s “spirit of openness” (开放的精神) as a means to “demystify” (去神秘化) the department, the day’s events were only attended by representatives of Chinese institutions (China Online; Voice of America, September 25, 2007). The next iteration included foreign media, as did subsequent events (The Paper, June 27, 2016). In April 2011, foreign journalists witnessed a meeting between the ILD and a German cross-party parliamentary delegation; in June 2011 they watched talks between the CCP and the Mozambique Liberation Front; and a 2016 event featured a public discussion between the ILD minister and First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba Raúl Castro (China Daily, April 11, 2011; Xinhua, June 10, 2011; The Paper, June 27, 2016).

Previous “Enter the ILD” events purposefully exposed what the department is and how it works. Although some aspects remained choreographed, from 2007 into the 2010s, the ILD was working to be understood by the country and the world. Its leadership shared data on the CCP’s links to political parties around the world and answered questions from foreign reporters on Party ties with counterparts in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), Vietnam, India, and elsewhere.

Publicized readouts from the ILD’s more recent student events show a shift from that earlier period. Instead of the department telling its own story, the ILD now answers Xi’s call to “tell the China story well” (讲好中国故事). In early 2025, Vice Minister Lu told Johns Hopkins students that “the PRC has maintained a high degree of continuity in its policy towards the United States” (中国始终保持对美政策的高度连续性), and rejected national responsibility for deteriorating U.S.–PRC relations (ILD, March 18, 2025). He also expressed hope that the students can “experience the genuine, three-dimensional, and multifaceted PRC” (感受真实、立体、全面的中国), a statement that contains common tropes related to “telling the China story” (ILD, March 18, 2025).

Table 1: Timeline of Public Meetings Between Foreign Students and ILD Leadership

| Organizer | ILD Host | Date |

| University of Pennsylvania | Ma Hui | July 11, 2024 |

| Columbia SIPA | Lu Kang | January 3, 2025 |

| Harvard Kennedy School | Lu Kang | January 21, 2025 |

| Johns Hopkins University | Lu Kang | March 18, 2025 |

| China–U.S. Exchange Foundation (Beijing) | Lu Kang | January 6, 2026 |

| Harvard University | Lu Kang | January 23, 2026 |

(Source: ILD, July 11, 2024, January 3, 2025, January 21, 2025, March 18, 2025, January 6, January 23)

The content of meetings also reflects the ILD’s shift away from purely managing the CCP’s foreign relations. Conversations have expanded to cover general foreign policy topics, not just party-to-party ties. Lu’s visitors from Harvard University asked questions concerning U.S.–PRC relations and cooperation, the PRC’s policy in Latin America and the Middle East, and Russia’s war in Ukraine (ILD, January 21, 2025). [1] Although presented as a technocratic tool to manage the CCP’s relations with foreign political parties and advance broader foreign policy goals, this provides further evidence that the ILD has adapted to an era defined by perceptions of rising national power.

Promoting PRC Global Leadership

In the past, changes to the ILD’s mandate and value were motivated by external factors. The Sino-Soviet split that began in the late 1950s increased the ILD’s significance by necessitating competition over relations with global Communist parties. Later, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War led the department to establish closer relations with non-Communist parties (Sutter, 2011). [2] These developments have translated into a growing scope for the department, which now deals with parties across the world and the political spectrum.

Unlike historical developments in the ILD’s work, the introduction of student outreach in 2024 was the result of an internal shift: the PRC’s growing comprehensive national power (CNP; 综合国力). By the 2010s, PRC policymakers and foreign policy experts determined that the country ranked second in terms of global CNP, motivating a more assertive foreign policy (China Brief, January 6). This confidence can be seen in then-minister Song Tao’s (宋涛) comments on the department’s role in 2016. He told a People’s Daily reporter that since “the PRC finds itself at the center of the global stage for the first time” (中国前所未有地走近世界舞台中心), “one of the main characteristics of the Party’s international work is political leadership” (政治引领是党的对外工作的主要特色之一). He elaborated, saying that the political exchanges the ILD are known for had become a means to achieve the goal of global leadership, rather than exchange being a goal in itself (People’s Daily, December 28, 2016).

Table 2: Expansions of ILD Mandate Over Time

| 1951–present | 1990s–present | 2010s–present | 2024–present | |

| Mission | Promote party-to-party ties | Promote PRC global leadership | ||

| Outreach | Communist parties | All parties & “political rising stars” | Think tanks & universities | |

Note: Each period of expansion reflects additional responsibilities; the ILD continues to promote party-to-party ties and conducts outreach with Communist parties to this day. (Source: compiled by the author based on Robert Sutter’s Historical Dictionary of Chinese Foreign Policy, Larry Diamond and Orville Schell’s China’s Influence and American Interests: Promoting Constructive Vigilance, and ILD materials)

The shift toward promoting PRC global leadership in the 2010s has since guided the ILD’s global engagement. In 2022, the department spent $40 million to build the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Tanzania, investing in CCP-aligned education for members of African political parties (South China Morning Post, February 26, 2022). It has also worked with the CCP’s traditional regional partners, such as the Cambodian People’s Party, the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party, and the United Russia Party to promote the One Belt, One Road (一带一路) initiative in their countries (Qiushi, August 16, 2019). These examples show the ILD promoting PRC global leadership abroad by drawing on the party ties that it has maintained for decades.

Over the last 15 years or so, the ILD also began hosting U.S. think tank delegations in Beijing. Since 2018, there have been at least 13 meetings with think tank representatives, ranging from research and policy organizations to U.S.–PRC exchange forums. These meetings were most frequent in 2025 (see Table 3). Think tank delegations represent the ILD’s first move away from institutional actors and toward politically-adjacent, if not peripheral actors. Student visits represent a further consolidation of this pivot.

No longer defined by insecurity, the ILD has taken assertive steps, both in 2018 and 2024, to move beyond traditional relationships with political institutional actors. If the ILD’s goal is to advance the PRC’s international leadership, then their meetings with students suggest that they believe young Americans may be receptive to such aspirations. They also see the target students—all from policy programs at elite U.S. institutions—as potential future political leaders, and as such worthy of cultivating (or at least influencing) from as early a stage as possible. The ILD has long invited political “rising stars” to Beijing, and they likely now see elite American students as meeting this criterion (Hoover, 2019).

Table 3: Recorded Think Tank Visits to ILD

| Institution | Year |

| Brookings Institution | 2025 |

| Eurasia Group (2 visits) | |

| Carnegie Endowment for International Peace | |

| CSIS | |

| National Committee on U.S.–China Relations | |

| Asia Society Policy Institute | 2024 |

| Paulson Institute | |

| CSIS | 2023 |

| Asia Society Policy Institute | 2019 |

| CSIS | |

| National Committee on American Foreign Policy | |

| National Committee on American Foreign Policy | 2018 |

(Source: Compiled by author)

United Front Channels Mirror University Engagement

Most student delegations to the ILD have been organized by universities, but one visit in January 2026 was organized through CUSEF, which describes itself as promoting exchange and mutual understanding by “mobilizing all available resources” (动员一切可以利用的资源) (CUSEF (Beijing), accessed January 19). These resources have included its connections to PRC government entities and the CCP’s United Front Work Department, a Party organ under the Central Committee dedicated to both domestic and international alignment with CCP interests.

CUSEF is supervised by the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC; 中国人民对外友好协会), a “mass organization” (人民团体) under the State Council (China Brief, June 21, 2024; CUSEF (Beijing), accessed January 19; Baidu Baike/中国人民对外友好协会, accessed February 10). CUSEF is also “guided” (指导) by a Hong Kong entity of the same name, which conducts similar work but places additional emphasis on high-level dialogues (CUSEF (Beijing), accessed January 19, CUSEF (Hong Kong), accessed February 10). CUSEF Hong Kong operates as a mechanism for foreign influence in the United States, with legal disclosures from 2010–2020 showing that it worked with seven lobbying firms to conduct outreach to House and Senate offices, and to manufacture think tank publications that align with Party narratives (China Brief, September 16, 2020). There is some overlap in the two organizations’ governing personnel, including Elsie Leung (梁爱诗), the former first Secretary of Legal Affairs of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (China Brief, September 16, 2020; CUSEF (Hong Kong), accessed January 19). The Hong Kong entity’s board of governors includes multiple representatives of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC; 中国人民政治协商会议), a central united front body that sits directly under the Party’s Central Committee (CUSEF (Hong Kong), accessed January 19).

Conclusion

CUSEF’s ties to the CCP explain why it would encourage American students to meet with the ILD, but the timing of the recent series of meetings shows how U.S. institutions have normalized these interactions. What might have seemed a step too far before 2024 now has an American-executed precedent. As the ILD brings youth engagement into its scope of operations, U.S. universities and CUSEF alike provide a vector for the ILD to advance its goals of promoting Party interests and PRC global leadership.

Minister Song’s comments on global leadership and the changing definition of “Enter the ILD” reflect the department’s shift from a platform for exchange to one increasingly oriented toward promoting the PRC’s global status. Foreign participants in ILD forums may not necessarily endorse PRC leadership or the Party’s perspectives, but their participation likely reinforces the department’s confidence, and provides it an additional layer of legitimacy. Given its expanded mandate since the 2010s, the ILD sees an opportunity to influence U.S. think tanks and universities, and meetings provide an outlet to assert its political aspirations as accomplished fact.

Notes

[1] Readouts from the University of Pennsylvania visit in 2024 and the CUSEF delegation in 2026 do not mention topics discussed. These readouts are limited only to a general outline of U.S.–PRC relations.

[2] Sutter, Robert G. Historical Dictionary of Chinese Foreign Policy. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011, p. 128.