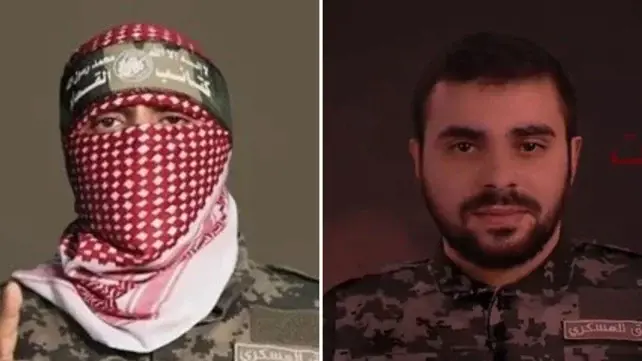

Saleh al-Arouri: A Postmortem of One of Hamas’s Key al-Qassam Commanders in Lebanon

Saleh al-Arouri: A Postmortem of One of Hamas’s Key al-Qassam Commanders in Lebanon

Executive Summary

- Hamas deputy leader and head of the West Bank al-Qassam Brigades Saleh al-Arouri was killed in a January 2024 Israeli drone strike while meeting with Hezbollah. He is the senior most Hamas leader killed by Israel since the start of the war.

- Al-Arouri was a founding member of Hamas in the late 1980s. He subsequently spent 15 years in Israeli prisons for establishing Hamas’s military wing in the West Bank. Following this, he was exiled, during which time he became a top Hamas political and military leader.

- An official Hamas turn toward moderation in 2017 caused some to assume that al-Arouri and a number of other radicals who took power at the time were more pragmatic than past leaders. The rising clique would be the same group that would eventually plan and execute the surprise attack on Israel on October 7, 2023.

Saleh al-Arouri was killed in a drone strike in Lebanon on January 2. His death was a major blow to Hamas and its military wing, the al-Qassam Brigades. At the time, al-Arouri was at the stronghold of Lebanese Hezbollah in south Beirut for a meeting with Hezbollah’s leader Hassan Nasrallah, which was reportedly scheduled for the following day (Sky News Arabia, January 2).

Al-Arouri was a prominent figure in the more radical wing of Hamas’s leadership, which planned and launched the surprise attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, starting the Israel–Hamas war. This wing also includes Hamas’s leader in Gaza, Yahya al-Sinwar, and its military wing commander, Mohammed al-Dhaif (Syria TV, November 9, 2023). As deputy chairman of Hamas’s political bureau and as a leader of the group in the West Bank, al-Arouri has performed a number of crucially important leadership roles for Hamas. Crucially, he has been the most senior Hamas leader killed by Israel since the start of the war.

Al-Arouri’s death will critically test Hamas’s ability to communicate effectively with key regional allies. This is because al-Arouri was in charge of Hamas’s relations with Iran and Hezbollah (amwaj.media, January 2). Those alliances have been extremely important for Hamas in the past, and they will grow even more important as the pressure on the group intensifies in the future.

In the West Bank and Beyond

Al-Arouri was born in the village of al-Aroura near Ramallah in the West Bank in 1966. He joined the Muslim Brotherhood in 1985—two years before the founding of Hamas—and studied Islamic theology. Al-Arouri became a cleric, earning the revered title of “sheikh” at a young age.

When the first Palestinian intifada broke out in December 1987, the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood reorganized the movement and introduced Hamas as a new political front which could serve as a Palestinian resistance movement with an Islamist conviction. Al-Arouri was a founding member of Hamas and its military wing, al-Qassam.

While most of Hamas and al-Qassam’s leaders have come from and lived in Gaza, al-Arouri played a major role in establishing al-Qassam’s branch in the West Bank. Al-Arouri had been arrested several times between 1990 and 1992 by the Israeli authorities for his role in Hamas’s military activities. When al-Arouri’s work culminated in 1992 and al-Qassam became operational in the West Bank, he was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to 15 years in prison for his role in the formation and activities of al-Qassam there. While he was in prison, al-Arouri advanced within the ranks of Hamas. During this time, the West Bank branch of al-Qassam which he had established commenced its well-known campaign of suicide attacks inside Israel. Hamas’s strategy was to destroy the peace process launched after the 1993 Oslo accords between the Palestinian Authority, dominated by Israel and Hamas’s rival Fatah (Sky News Arabia, January 3).

Israel released al-Arouri after he served his 15 years in prison in 2007, only to arrest him a few months later. He was finally released in 2010. Realizing his operational influence, Israel then expelled al-Arouri to Syria. In 2012, al-Arouri relocated to Turkey, later moving to Lebanon. In this way, he could become closer to Hezbollah while also remaining near the Palestinian territories. Between his release in 2012 and his death in the 2024 Israeli air strike, al-Arouri had many essential roles in the leadership of Hamas and al-Qassam. These included being a military commander, a political leader, and a chief negotiator. In 2021, when he was reelected as deputy chairman of Hamas’s political bureau, al-Arouri was also elected as Hamas’s leader of the West Bank, complementing his position at the helm of the al-Qassam in the West Bank (Al Jazeera, January 6).

Hamas Leadership and Change

Al-Arouri assumed his senior position in the leadership of Hamas in 2017. He was made deputy head of the political bureau in that year, which was a turning point in Hamas’s history (Ammon News, October 5, 2017). Hamas was founded by the Palestinian Islamist organization of the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1980s. In its founding document, Hamas embraced a hardline ideology that committed the group to launching jihad against Israel and the Jews. [1]

However, in 2017 a new manifesto was adopted to replace the old one, which was perceived to be more moderate and realistic, as well as less radical. This happened to coincide with the ascendancy of al-Arouri and other radical figures to top leadership positions, causing those individuals to be perceived as becoming more pragmatic. This view would prove to be fatally misguided (Youm7, May 1, 2017).

The year 2017 was a turning point in the history of Hamas, but not towards moderation. Leaders of Hamas’s military wing became the actual leaders of the entire movement. Al-Sinwar, for example, became the leader of Hamas in its stronghold, the Gaza strip, where the group controlled the government. His predecessor, Ismael Haniya—a Gaza native like al-Sinwar—became the chairman of the political bureau outside Gaza. As a result, Haniya moved to Qatar. Al-Arouri, meanwhile, became deputy chairman of the political bureau outside Gaza, while maintaining his role as leader of al-Qassam in the West Bank (Al Jazeera, May 10, 2017).

Al-Sinwar and Al-Arouri as Hamas Heads

The “Sinwar-Arouri” wing of Hamas has become dominant in the group’s decision-making since 2017. Al-Sinwar focused on rebuilding relations with Egypt, which were damaged after the Egyptian seized control of the government in 2013 from the Muslim Brotherhood. The latter shares its roots and ideology with Hamas (i24News, June 18, 2017).

Al-Arouri, on the other hand, took up the more difficult mission of reviving relations with Hamas’s main backer, Iran, and Iran’s proxy in Lebanon, Hezbollah. Those relations had soured because Hamas, a Sunni group, sympathized with the mostly Sunni uprising against the Alawite Shia-dominated regime of President Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Al-Assad had been supported by Shia Iran and Hezbollah. Al-Arouri, who himself had to leave Syria when Hamas severed its relations with Damascus in 2012, admitted later that Hamas should have prioritized its well-established relations with Syria and its backer, Iran. Al-Arouri further argued that Hamas should not have taken sides in the Syrian conflict. Al-Arouri did not only offer words, but undertook serious efforts to revive relations with Iran’s “Axis of Resistance,” which includes Hezbollah (Saida Online, January 10).

Recreating al-Qassam

The degree of al-Qassam’s development since 2017, especially in the areas of training, strategic leadership, and (more critically) weaponry, shows how successful al-Arouri was in his mission. Support from Iran and Hezbollah was key in making al-Qassam the fighting power that it has become. Not only did al-Arouri play a key role in overseeing the flow of support to al-Qassam, but he performed this task in a way that did not attract too much attention—which would have provoked counter-measures—from Israel. The general Israeli assessment was that al-Sinwar’s government would be focused on governance in Gaza and avoid major military escalations with Israel. The 2021 war where Hamas showed unprecedented missile capabilities and the group’s surprise attack on October 7, 2023 both demonstrate the degree of combat development that al-Qassam acquired in recent years. This was unquestionably due to the work of men like al-Sinwar, al-Dhaif, and al-Arouri (The New Arab [United Kingdom], January 5).

Al-Arouri was not entirely off the Israelis’ radar, however. The 2014 Gaza war began when Israel retaliated to an attack al-Arouri was accused of plotting, which involved the kidnapping and killing of three Israeli teenagers. In 2015, he was also sanctioned by the US Department of the Treasury for his role in leading al-Qassam in the West Bank and his involvement in coordinating financial support for Hamas. Three years later, the US State Department offered a $5 million reward for information leading to al-Arouri’s identification or location (Rewards for Justice, November 13, 2018).

Conclusion

The rise of the al-Sinwar wing in the Hamas leadership did not mean that there was a rift with the leaders who were based outside of Gaza, and especially in Qatar. However, al-Sinwar’s wing started the October 7 operation and has been running Hamas’s war effort ever since. The al-Sinwar wing is the military wing, and that wing has now lost al-Arouri, who is a founding member of al-Qassam. Al-Arouri flexibility of movement, the mandate that he enjoyed from the Gaza-based leadership, and his contacts and established relations with foreign supporters—especially Iran and Hezbollah—means that he will not be easily replaced.

Notes:

[1] Find the full Hamas founding document as issued in August 1988 via this link from The Institute For Palestinian Studies: https://oldwebsite.palestine-studies.org/sites/default/files/Charter_of_the_islamic.pdf